To boldly go where no man-made object has been before

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It has travelled further than any man-made object. Now, after a voyage lasting more than 33 years and covering about 11 billion miles (that's 230,000 trips to the moon and back) it is now is on the verge of leaving the Solar System to enter the mysterious region of interstellar space where no man – nor even anything terrestrial – has gone before.

Scientists at the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) said that the Voyager 1 space probe has entered the cosmic equivalent of the doldrums, where the high-speed solar winds die down at the very edge of the Solar System.

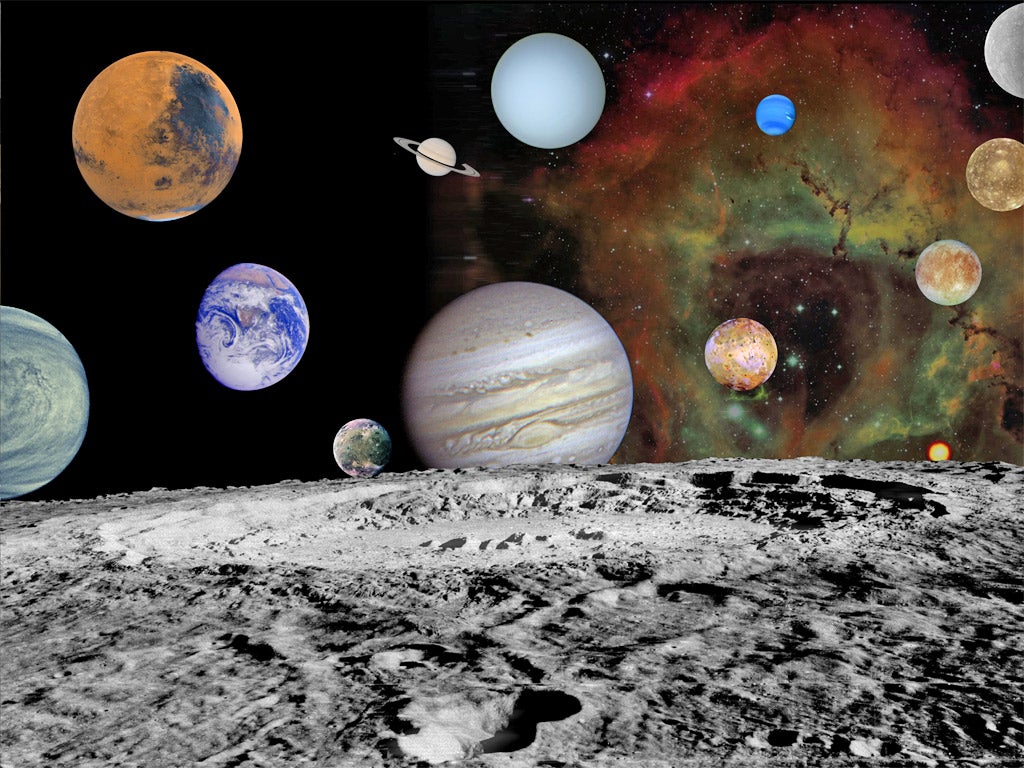

Voyager 1, launched within weeks of its twin probe, Voyager 2, was originally designed to explore Jupiter and Saturn. After making a string of important observations, such as active volcanoes on Jupiter's moon Io and the intricacies of Saturn's rings, the mission was extended. Voyager 2, meanwhile, went on to explore the far-away planets of Uranus and Neptune.

However, long after the official planetary missions ended, both space craft continued to plough through the furthest regions of the Solar System, while maintaining radio contact with mission control through its Deep Space Network.

Nasa expects that within the next few months, or possibly years if margins of error are taken into account, Voyager 1 will finally leave the Solar System for good and begin its journey through the vast void of interstellar space that comprises most of the Milky Way galaxy. Voyager 2 – travelling not far behind – will follow suit.

Scientists at Nasa said that over the past year, Voyager 1 has entered a kind of "cosmic purgatory" where the wind of electrically-charged particles streaming from the Sun has calmed.

Both spacecraft are now in a region known as the "heliosheath", the outermost layer of the Solar System where the solar wind, which can travel 26km per second, is being slowed down by the rising pressure of interstellar gas. Nasa scientists believe this indicates the imminent entry of Voyager 1 into the interstellar region, which is dominated by another kind of magnetic wind coming from a different direction of deep space.

"Voyager [is telling] us now that we're in a stagnation region in the outermost layer of the 'bubble' around our Solar System. Voyager is showing that what is outside is pushing back. We should not have long to wait to find out what the space between the stars is really like," said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Nasa changed the orientation of Voyager 1 on four separate occasions earlier this year to see whether the solar wind and magnetic field lines have switched direction. Data released at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco show that the magnetic field lines have not changed, indicating that Voyager 1 is still just within "heliosphere", the magnetic bubble of charged particles created by the Sun.

"We have seen the same east-west direction of the magnetic field since we launched. That's the solar magnetic field. Once we leave the heliosphere we will enter the magnetic field of the galaxy and all the data to date suggest that this field is orientated more north-south," Dr Stone told the meeting.

"It's reasonable to think that it will only be a matter of months or years before we cross this region and into interstellar space, but no spacecraft has ever been there before and that transition may not be instantaneous," he said.

Rob Decker, a Voyager 1 investigator at Johns Hopkins University in Laurel, Maryland, said that researchers have been able to use the spacecraft as a kind of "wind sock" to determine the speed and direction of the solar wind billions of miles from Earth. "We've found that the wind speeds are low in this region and gust erratically. For the first time, the wind even blows back at us. We are evidently travelling in completely new territory," Dr Decker said.

"Scientists had suggested previously that there might be a stagnation layer, but we weren't sure it existed until now," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments