'His was a life that did not know dullness or boundaries'

Geordie Greig remembers Lucian Freud, a leading figure of 20th-century art

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At 9pm last night waiters at London's Wolseley restaurant, where Lucian Freud dined most nights, covered his corner table with a black table cloth and lit a single candle in tribute to the greatest realist painter of the 20th century.

Freud lived always to paint and he died quietly at his home surrounded by his family. He painted to the very end; until a few days ago he was still working on a vast portrait of David Dawson, his devoted assistant of 20 years. Aged 88, he was also finishing a female nude and two etchings.

For almost 70 years his focus was to create in paint what he saw before him in all its intense reality. His vision was raw, naked, intense and undisturbed, be it his dying mother, a naked man with a rat by his genitals, his own naked self-portrait.

It was an extraordinary life: escaping Hitler's Berlin where he was born, arriving in England aged 10, becoming a British subject in 1939. Grandson of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, he rose to his own huge prominence on the global stage, his art the most highly priced of any living artist.

Twice-married, he had many lovers, at least a dozen children, an eclectic coterie of loyal friends. For a man who was intensely private and supposedly reclusive he got out a lot. Into his mid-eighties he skated at Sting's Christmas party in Wiltshire, watched the ballet at Covent Garden and then ended up at Annabel's dancing with Kate Moss until 3am.

For many years I wrote to him asking for an interview. Then one day I opened a letter with handwriting so child-like that I thought it was from my niece. "Dear Mr Greig, Your suggestion of interviewing me for my Tate show next year makes me sick. But if I am alive then I will consider it."

Then in 2005 I wrote to say I had an idea but I could not tell him what it was. I expected no reply but my mobile rang at 6am. Meet me at 6.30am at my studio, he said.

My idea was not to interview him but to photograph his friend, the painter Frank Auerbach, but would he consider also being in the picture as they always have breakfast together? It was a yes. My first sight of him was opening the door to his studio in striped trousers, a white shirt, intense eyes piercing but his manner utterly engaging and beguiling. His candour and charm were beyond that of anyone I have ever met. It was the beginning of a cherished friendship.

He loved being on his own but not alone, choosing who he saw and when. He told me if he had a chauffeur take him to a cinema he would then move to another so that no one knew where he might be. Freud painted day and night, but he also lived. He had danced with Garbo, stayed with Ian Fleming in Jamaica, befriended Bacon, Spender, Auden. His was a life that did not know dullness or boundaries.

But always his day turned on a rigorous regime of painting round the clock. He wanted more than anything else to paint the best paintings. He also cared for the best things in life, but disdained any rules.

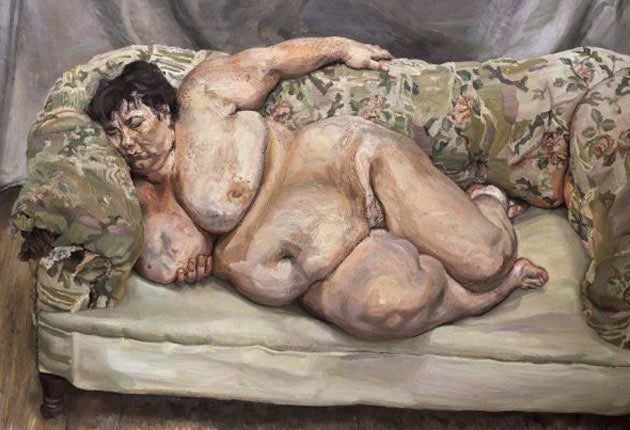

His prices rocketed and he became the most expensive living painter when Benefits Supervisor Sleeping fetched £17.2m. The price was of intense interest to him but not the money. Money was never a priority or even important.

He held the strongest views on art and enemies, loathing his brother Clement, for instance. His taste was unswervingly good, his dandyism uniquely bohemian. He was beyond definition.

And he was the most loyal of friends, a father and grandfather adored to the end. His family gathered in the last few days and weeks to be with the man who had always spent all his time devoted to his art. "Of course, I am selfish," he said. "I always want to paint."

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in yesterday's London Evening Standard

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments