Are running trainers doing more harm than good to your feet?

Evidence suggests that the first footwear emerged around 30,000 years ago – meaning for most of upright-human history we were barefoot. Peter Francis asks sole-searching questions

It was around four to six million years ago when humans first evolved to walk upright. We continued to evolve into superb long-distance walkers and runners, made possible by our arched feet, long achilles tendon, and ability to cool through sweating. And surprisingly, for most of human history this long distance travel was done barefoot.

Some evidence suggests footwear emerged around 30,000 years ago. But it wasn’t until about 100 years ago that fashionable footwear was reported to be altering the shape of the foot. Since the 1970s, cushioned running shoes have become synonymous with exercise.

But a growing body of evidence shows running shoes might actually be doing us more harm than good. Our latest review suggests that wearing shoes changes the way we run and weakens the foot in a way that can contribute to many common sports injuries.

Previously, our team revealed that we can still run barefoot, especially if we start young. We found that not only could children in New Zealand aged 12 to 19 run sprint and middle-distance races barefoot, we also found the prevalence of pain in the knees, ankles, and feet was relatively low compared with children of similar ages from other countries. Other research has also shown differences in foot structure and function in barefoot and shoe-wearing populations.

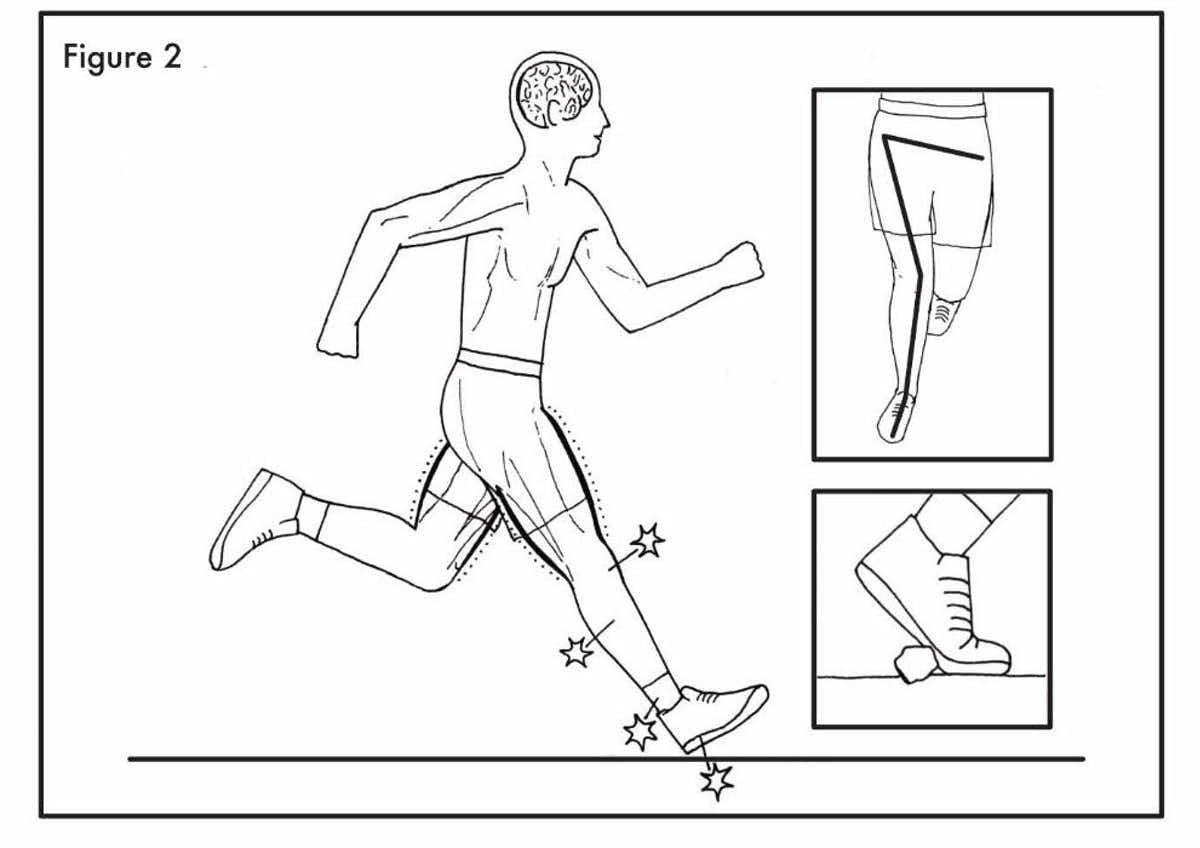

These findings prompted us to conduct a global review of running injuries in men and women. We found that between 35 and 50 per cent of runners were injured at any one time. These numbers could be considered high – especially for a species adapted to long-distance running. The most common injuries were to the knees, shins, ankles and feet. Most of these injuries were mainly to bone or connective tissue, whose primary function is to help transmit force from the muscles to allow movement.

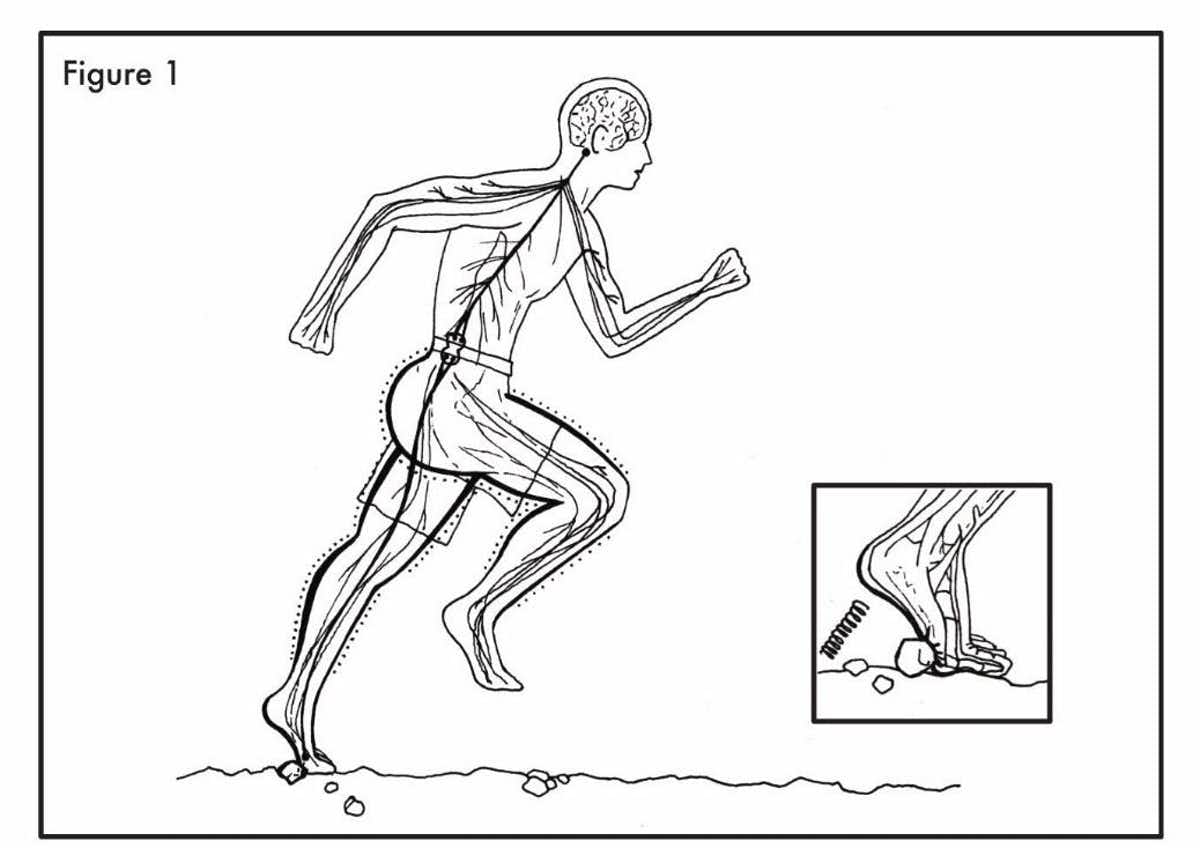

Our latest review explored how humans ran before using shoes, and how shoes change the way we run. We found that when the foot comes into contact with the ground, the skin, ligaments, tendons and nerves of the foot feed a rich source of information to the brain and spinal cord about the exact position of our foot, including tension, stretch and pressure. The quality of this information allows the precise control of muscles to move our joints into a position that absorbs impact and limits damage.

The first mass-marketed cushioned running shoe was manufactured in the 1970s and advertised as footwear that could prevent running injuries. Surprisingly, this narrative even found its way into the scientific literature. In the 1980s, “better running shoes” were suggested as a reason for the reduced incidence of achilles tendonitis in one study and “poor shoes” were suggested as a risk factor for stress fractures in another study.

In fact, barefoot runners appear to report fewer knee injuries and less heel pain compared to runners who use shoes

Our review suggests that footwear reduces the quality of information being sent to the brain and spinal cord, leading to more blunt running mechanics. Shoes allow runners to land with a more upright body position and an extended leg, leading to excessive braking forces. These running mechanics seem to play a role in some of the most common running injuries.

Long-term everyday use of footwear also leads to a weaker foot and often, a collapsed arch. When we start running in shoes, our feet aren’t adapted to cope with these mechanics.

But this damage might be reversible. Interestingly, one study found that foot muscle size and strength were found to increase after eight weeks of walking in a minimalist shoe. This is because removing the cushioned heel and arch support made the foot’s muscle work harder.

Balance activities are also recommended to improve proprioception, which is our awareness of our body’s position and movements. This type of training aims to prevent or repair injuries. Using equipment like a wobble board will create more unstable or less predictable conditions under foot, which builds lower limb stability and foot strength.

But the simplest and perhaps most specific form of proprioceptive training for runners is to take off their shoes and walk or run. In fact, barefoot runners appear to report fewer knee injuries and less heel pain compared to runners who use shoes.

However, barefoot runners do report more calf and achilles tendon injuries. This suggests that people who transition too quickly to barefoot activities may overload their muscles and tendons. This might be because barefoot runners usually have a shorter stride and more flexed hip, knee and ankle. They also tend to run more on the tip of their toes.

Peter Francis is a lecturer in sport, exercise and rehabilitation science at Leeds Beckett University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks