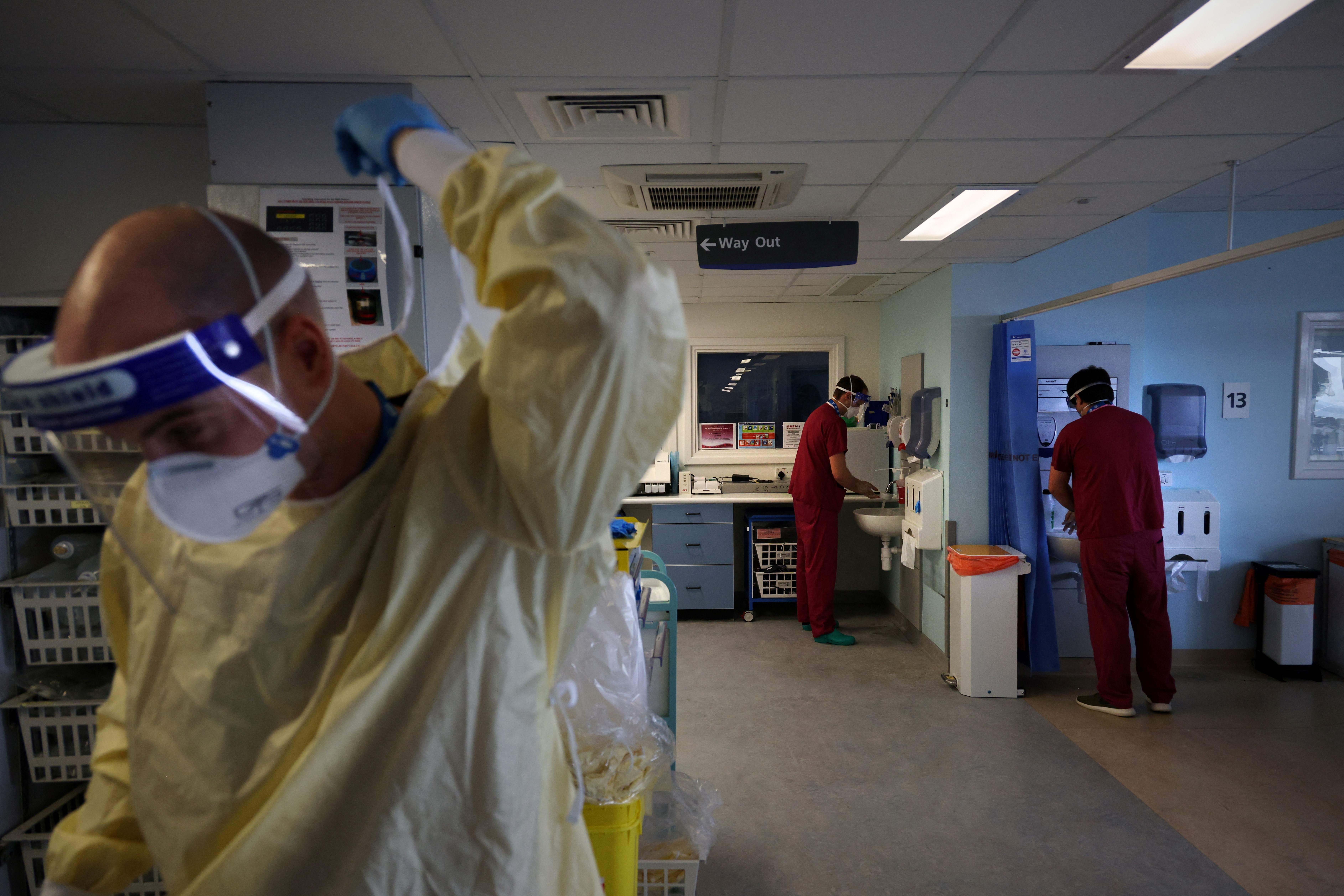

Two doctors explain how we’ll treat Covid in the future

The chances of completely eliminating Covid-19 from out lives are extremely unlikely for the next few years – instead we will have to learn to treat it and manage it. This is what that might look like, write Dr Tom Wingfield and Dr Miriam Taegtmeyer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As people across the UK start returning to pub gardens and outdoor dining, and with indoor socialising looking set to return from 17 May, it feels as if the long, hard third wave of Covid-19 is ebbing away and life is slowly returning to some kind of normality.

But the reality is that this disease is still in full swing. It is still devastating other parts of the world including Brazil and India, and it is clear that we will all have to live with Covid-19 for some time – if not forever.

The widely debated “zero Covid” strategy, to eliminate the virus from a region or country, is laudable, but without concerted and effective travel, quarantine and contact-tracing measures, it will remain a beautiful dream.

The more likely reality during our lifetime is prevention, mitigation, and compassionate care of victims of seasonal Covid-19, for which we must start planning now.

So, if we assume that Covid-19 will become endemic, what will the future of care for patients look like?

The long haul ahead

The endurance test of UK’s post-Christmas Covid-19 peak showed how much we all crave “normal” human contact, touch and communion. However, it also laid bare the perils of transmission in communities with low levels of immunity.

A recent pre-print – a study that has not been reviewed by other scientists – suggests that nearly half of people hospitalised with Covid-19 report not feeling fully recovered on average seven months later

It is entirely understandable that many hope mass vaccination will support us to get our lives back.

The speed of the development, evaluation, and roll-out of highly effective vaccines is unparalleled. The UK government aims to have offered a first dose of vaccination to the entire population by August 2021.

But vaccine uptake varies widely. Although the gap is narrowing, people from black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds, including healthcare workers, still appear less likely to be vaccinated. This finding is also reported in those from poorer areas or with chronic illnesses. Similarly to other vaccines, efficacy may be lower in people with cancer.

Even with high vaccine coverage, we are likely to require vaccine adjustment to cover new variants. We may never achieve herd immunity and no Covid-19 vaccine is 100 per cent effective.

As clinicians, we should also be aware that people who are re-infected, or who were previously vaccinated and become ill with Covid-19, may present with new, attenuated or unusual symptoms or syndromes. This is especially the case for those with impaired immune systems.

Innovations in treatment

The good news it that we are learning more and more about how to treat people with Covid-19.

Thanks to the Recovery trial run by the University of Oxford, we now know that the cheap and widely available steroid dexamethasone reduces the number of deaths in people hospitalised with Covid-19 who require oxygen.

There are also encouraging results that indicate that the drugs tocilizumab and sarilumab may have a role in treating severely unwell, hospitalised people. These drugs act by reducing the body’s inflammatory response to Covid-19.

Further research is being conducted to find out if synthetic “monoclonal” antibodies or inhaled steroids can prevent deterioration and admission to hospital.

People hospitalised with Covid-19 are at high risk of developing blood clots. There are multiple studies that show blood-thinning medicines can prevent and treat Covid-19 clots and improve outcomes. But increased use of blood-thinning agents will increase the number of people experiencing their recognised side effects, including bleeding. Using these medications more widely will require us to strike the appropriate balance and ensure that we monitor patients carefully.

Although the advances above are monumental, medicines and tests alone are not enough. We need to ensure people are at the heart of the care we provide.

Patient satisfaction

Understanding the perspectives of people with Covid-19 is a good starting place.

In our Liverpool hospital, we have conducted satisfaction surveys of people admitted with Covid-19 throughout the pandemic. These are the first reported studies about the perceptions of people hospitalised with Covid-19 in the UK.

Our first-wave results showed satisfaction with the care received was high and patients felt safe on the wards. It also revealed some areas for improvement, including communication about medications and their side effects, food and sleep quality.

To improve patient care, in August 2020 we implemented an educational package for healthcare workers looking after people with Covid-19. Following the training, our preliminary second and third wave results showed improved care ratings, especially with regard to communication. The results also suggested that people of black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds reported similar satisfaction to white people.

The results are particularly encouraging given the pressures on the NHS at the time the survey was carried out.

The spectre of long Covid

“Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection”, otherwise known as long Covid, may complicate the future of care.

A recent pre-print – a study that has not been reviewed by other scientists – suggests that nearly half of people hospitalised with Covid-19 report not feeling fully recovered on average seven months later.

Indeed, as many as one in 10 of all people with Covid-19, including children, will have ongoing related symptoms some months later. This suggests that there will be millions who fall into this category around the world.

Predicting who will get long Covid is tricky. Aside from age and obesity, common risk factors for Covid-19 do not correlate with long Covid risk. In contrast with Covid-19 acute illness, working-age women are most likely to be affected by long Covid, according to another pre-print study.

It is clear that the best way to prevent future cases of long Covid will be to avoid infection in the first place. But for those who do acquire long Covid, funding has been made available to expand care at specialist centres. However, evidence-based treatment and return-to-work schemes for Covid-19 remain scarce.

Garnering the required evidence to treat long Covid will require better disease recognition, diagnosis and reporting.

Virtual healthcare

Throughout the pandemic, healthcare professionals have had to become adept at virtual consultations.

In future, there will be a more blended approach to communication. This will combine in-person consultations, video, phone and two-way messaging platforms. It is also likely that, as per the NHS Long Term Plan, other digital innovations such as wearable monitoring and tracking devices will become more widespread.

We have to work hard to ensure that such advances do not leave out people with limited access to the internet, including the elderly, poorer households, the learning disabled, those with language barriers and migrants.

Compassionate health systems

As UK Covid-19 cases continue to decline, reinstating routine and essential health services for non-Covid conditions is vital.

In January 2021, more than 100,000 people were admitted to hospital with Covid-19. Despite this, the NHS still managed to offer non-Covid care to 1.3 million patients, more than during the first wave’s peak in April 2020.

However, recent NHS figures show an increasing backlog of millions of people awaiting cancer care and planned surgery. Mental health services and those for other chronic illnesses, such as diabetes or lung disease, are also predicted to see increased demand.

Getting “back to normal” is likely to involve additional clinics, surgery and work compared to previous years.

This will need to be delivered by a mentally scarred, depleted workforce, many of whom are now looking to reduce their hours or leave the NHS entirely. Alongside this, junior healthcare workers will need to make up their lost training hours, and rotas must be in place that are sufficiently flexible to deal with future Covid-19 surges.

A compassionate health system must be accessible and relevant to the diverse populations it serves.

We need to plan for these surges now, but without additional long-term investment and funding, and strong leadership, this is unlikely to be possible. As healthcare workers, we can make changes to improve our own practice. But these are a drop in the ocean compared to the wholesale changes in institutional values that are needed.

The government’s white paper on the future of the NHS fails to address funding and investment shortfalls. Nor does it provide a route towards narrowing the gaping breach between health and social care.

The bigger picture

A compassionate health system must be accessible and relevant to the diverse populations it serves. The 2020 Marmot review reported that health inequalities in England have widened since 2010. Covid-19 has exacerbated these inequalities.

Liverpool City Region is ranked as one of the most deprived in England. In our daily work, we have seen more Covid-19 illness and worse outcomes among people who are poor, unemployed or in precarious employment, or who face challenging living circumstances, including overcrowding and poor-quality housing.

There are also large health disparities and marginalisation related to ethnicity. While some ethnic disparities overlap with poverty or other forms of disadvantage, racism itself is a fundamental structural and cultural driver of inequality.

Read More:

Health systems need better strategies to address racism and reach under-served and ethnic minority groups. Building trust and networks with local communities will be crucial to achieve this.

Without such measures, existing inequalities will have long-term, negative intergenerational impacts on health, educational and economic prospects.

Amid the major planned restructuring of the NHS, it is clear that a compassionate workforce won’t be enough to continue to care for people with Covid-19 or any other illness. Instead, we need a compassionate health system that works for everyone.

Dr Tom Wingfield is an infectious diseases physician and senior clinical lecturer at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and an Honorary Research Associate at the University of Liverpool. Dr Miriam Taegtmeyer is a professor of global health at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments