Psychosis, alcoholism, anxiety: What happens when LSD never wears off?

You might have experienced ‘a bad trip’ and a certain audience will be familiar with flashbacks. Yet for some people the effects of these drugs never went away. Ed Prideaux reports on the rise of psychedelics as healing treatments and urges caution

When most of us look around a room, nothing much seems to happen. The walls will look like walls; the computer like a computer; and unless you’ve had a few coffees or too much wine, you’ll likely feel fairly ordinary, too. But some of us aren’t so lucky. Jay is based in Bewdley, a small riverside town just outside of Birmingham. He works as a programmer. He’s reluctant to communicate on Skype or Zoom, but agrees to use email.

“Looking up at a wall, I see dark lines from the text I’ve been reading. My entire visual field is covered in snow and strobe flashing persists. Large green and blue geometric patterns dance around the white wall.

“As I look at the top of the TV, I see what I can only describe as vortexes: little green tornado-like visuals that move around and merge into each other. And looking at the wooden table, the patterns begin to breathe and warp, but only if I stare in the same place.”

Reading this, you’d assume that Jay was on something far stronger than coffee or red wine. His descriptions, like something out of a 1960s period piece, may recall the visions common to drugs like LSD or magic mushrooms. You’d be half-right. The thing is, though, that Jay last took LSD in 1995. He was 18 then. And for the past 25 years, he has lived daily with its effects.

“I took a microdot at Glastonbury and had a very intense but good trip,” Jay recalls. “The next morning, after waking from a few hours’ sleep, I felt a very strong difference in my mental thinking. I could see a full hallucination of a cathedral on the tent roof and felt like I was still tripping. Being young and dumb, I masked this by drinking, smoking weed and taking MDMA for the rest of the weekend.”

The psychedelic feelings persisted long after. “It was only during a two-week trip to Spain, where I had no drugs to hand, that I started to understand this problem might not go away.”

For many readers, and particularly those raised in the 1970s and 1980s, they’ll recognise that Jay has a case of “flashbacks” – when the visions and feelings brought on by a psychedelic drug persist after they should have subsided. And unlike many old wives’ tales from the Just Say No era, flashbacks are a very real – and sometimes very dangerous – side-effect.

Flashbacks are known clinically as a condition called Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder, or HPPD. Psychedelic drugs of all shapes and sizes can cause it. LSD is considered the most common culprit, followed closely by hallucinogens like magic mushrooms, 2C-B, DMT, mescaline and DXM, and sometimes less explicitly psychedelic-style drugs like MDMA and cannabis.

No one knows for sure how HPPD works or how common it is. There has never been a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Much of the relevant literature covers chronically low samples of patients, including some with case studies of only three people. No cure or much in the way of treatment has been found, and proper neuroimaging studies of HPPD-affected brains haven’t been conducted. The disorder attracts very little funding, too, or at least compared to classical mental illnesses such as depression, generalised anxiety and schizophrenia.

HPPD’s leading theory links the condition to a “disinhibition” in the brain. Modifying the nodes that control vision, emotions and conceptual thinking, the drug can lead to a surge of neural circuits that doesn’t fully switch off once it leaves the body. The result: a raft of truly striking effects. The most common is “visual snow”, when the visual field is peppered by a coating of ephemeral whitish dots, not dissimilar to the static screen of an un-channelled TV. Another is “trails”: the appearance of an object’s motion through the air in several still-standing and ghostly pictures.

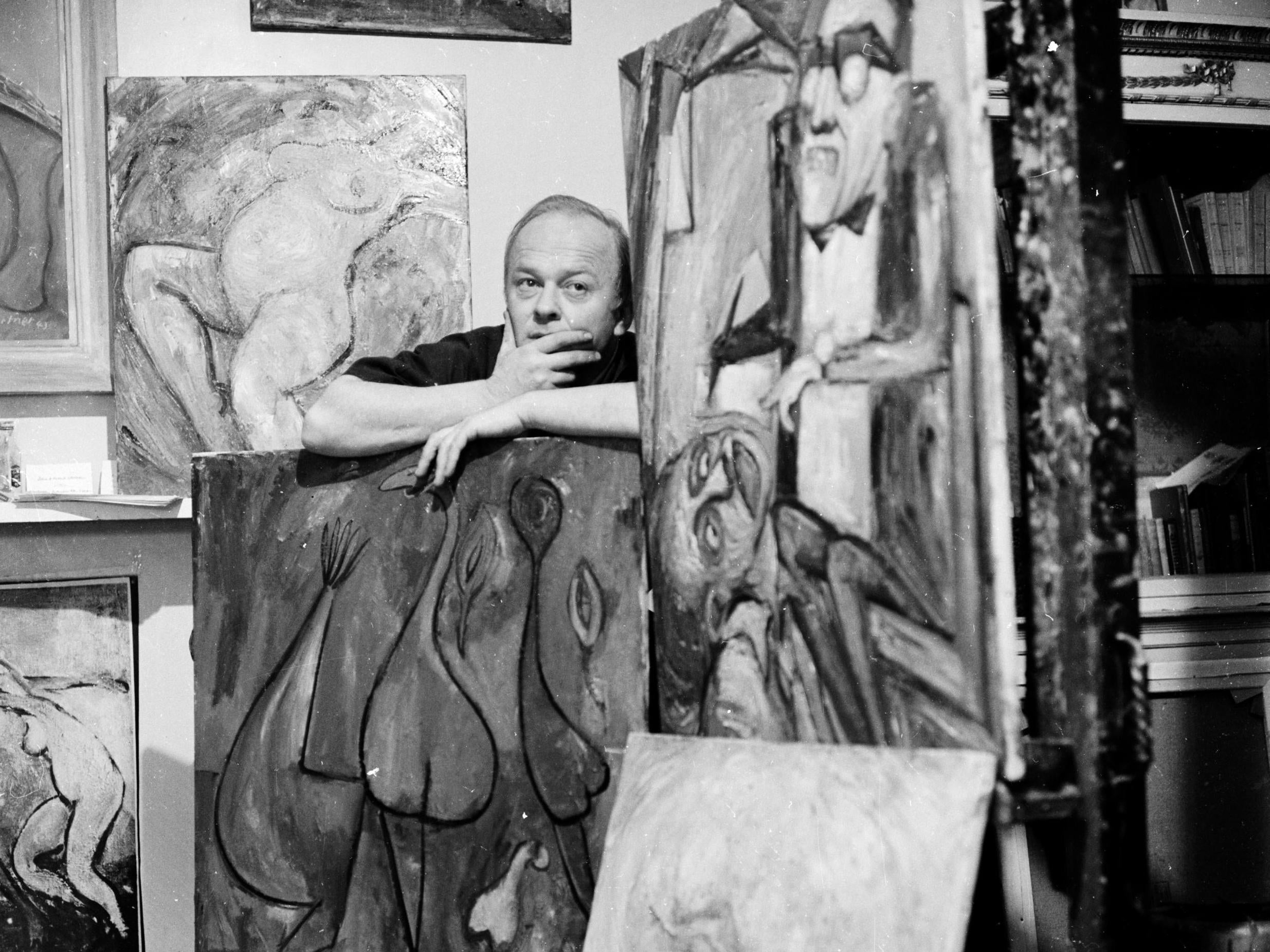

“After-images” are also common. These occur when the silhouette of an object – sometimes trimmed by bright colours of rainbow and neon – appears after one has already looked away. Haloes, blue-field phenomenon and full-blown psychedelic designs occur often as well. Some even report seeing animate beings. The French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre, for example, complained of being followed by crabs after a trip on mescaline.

Some even report seeing animate beings. The French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre, for example, complained of being followed by crabs after a trip on mescaline

Physical effects aren’t unheard of. Many sufferers report feelings of head pressure, as if their brain is sinking and pressing against their skull. Tingling and sometimes-pleasant excitations can suffuse across the body, reminiscent of the physical euphoria experienced under a psychedelic high. These effects follow two broad categories. Like a classical flashback, Type-1 HPPD describes a temporary lapse into a psychedelic consciousness; Type-2, meanwhile, encompasses something more enduring, with the effects a part of sufferers’ everyday life and experience.

With sobriety and enough time – some months, others several years – around half of patients will eventually return to normal. Many will make use of prescribed medications, although they’re not always effective. Benzodiazepines, a drug class that includes Xanax and Librium, are used to take the edge off. Resuming the use of psychedelic drugs and smoking cannabis especially can cause symptoms to resurface or further intensify.

When it comes to severity, the symptoms of HPPD can range wildly. Where some report only a distant layer of the visual snow, others like Jay are still fully in the throes of their last acid trip. A few months on from his post-Glastonbury holiday in Spain, Jay’s reported symptoms are among the most extreme I’ve ever heard. “My visuals were a kaleidoscope of colours, geometric shapes and visual snow. After-images lasted dozens of seconds and my entire visual field flashed like a strobe light around eight times a second.

“Perhaps worse than the visual issues were the intense feelings of still being on a trip. My thought processes were no longer linear. I felt like I was having multiple thoughts at once; thinking backwards, thinking sideways. This was further compounded by an intense anxiety and depression.”

Some will have a sensitive neurophysiology and develop the disorder after one to 10 trips; others around 50; some hundreds; and still others will never get it at all

The condition got so bad, in fact, that Jay was forced to abandon office work in London after only a few weeks. He prefers email over face-to-face, he says, because of “trippy thoughts” and panic attacks. He’s had to work from home for years. Can he drive, I ask? No. “I do not trust what I am seeing and my sense of depth is completely off.”

A psychedelic renaissance

In recent years, most news about psychedelic drugs has been singularly positive. Amid a so-called “renaissance” in psychedelic therapy, studies suggest that drug experiences can eradicate fear of death, reduce the symptoms of PTSD and anxiety, address migraine headaches, and even trigger full-blown mystical experiences.

Psychedelic finance and drug-based start-ups are appearing too. MindMed, one such start-up, made a splash in the trade media last month through the apparent discovery of an LSD “off-switch” that can reverse the drug’s effects during a trip. A new documentary on Netflix, Have A Good Trip, is the media’s latest addition. Against cartoon backdrops of lysergic shapes, dripping walls and talking plants, celebrities such as Sting, the late Anthony Bourdain and A$AP Rocky share tales of their most memorable trips. Some disturbing, others moving, their trips are told with the ambience of a veteran returning from a great and majestic battle.

Have A Good Trip also features advice. Don’t drive, avoid looking in the mirror, watch out for “set and setting” (or the mental state and physical environment with which you enter the trip). If you have a pre-existing mental health problem, they explain, tripping probably isn’t for you either. If you fail these tests, a bad trip – when the psychedelic experience is panicky, depressive and sometimes profoundly negative – may be on the cards. Conspicuously absent from the film, though, is any mention of HPPD. While one would expect a “thorough investigation of psychedelics” to include their more major risks, awareness about HPPD seems structurally lacking.

An unforeseeable condition

A poll of 200 members of Reddit’s HPPD community suggests that just under two-fifths had never heard of the condition before developing symptoms. More than half had read very little prior to taking a drug. One wonders whether the film’s director Donick Cary or any of its famous faces knew HPPD existed at all. A big problem with HPPD is that the condition cannot be reliably foreseen.

Dr Henry Abraham is a psychiatrist, a lecturer at Tufts University, and the world’s leading authority on the disorder. It depends on your genetic profile, he explains. Some will have a sensitive neurophysiology and develop the disorder after one-to-10 trips; others around 50; some hundreds; and still others will never get it at all. And in the absence of further research and the development of a genetic test, no tripper can know for sure whether they’re immune, or how many doses they can safely take.

Can you really get HPPD from one trip, you ask? “Yes. Next question?

More than the visual effects, Abraham sees the most profound damage in HPPD’s “comorbid conditions”: the symptoms of other mental health problems that arise concurrently with HPPD. Among those diagnosed, he explains that half will develop a generalised anxiety or panic disorder; the same number clinical depression; a quarter alcohol dependence; and one-tenth a disorder of psychosis, when someone loses touch with reality through hallucinations and delusional thinking.

So serious is the link to mood and panic, in fact, that Abraham suggests HPPD could be better-classed as an anxiety disorder.

Does the anxiety come from how the patient responds to the condition, or is it an element of the condition itself? Both. As well as disinhibiting the visual cortex, HPPD can shift elements of the brain controlling mood and emotion. In the same way that new and fantastical images appear and flood one’s line of sight, unusual and highly charged thought patterns can emerge too.

Mark is based in the Middle East. Now 33, he developed HPPD from a trip on LSD and MDMA when he was 18. “My worst troubles were always this weird anxiety that seemed to envelop me like a blanket,” Mark describes over email. “I was never actually worried about the external circumstances of my life; I had a decent relationship with my family, I didn’t have some deep, dark, mysterious, unresolved trauma that I was repressing, and yet my brain felt plain damaged.”

The anxiety is amplified when HPPD sufferers have trouble adjusting to their symptoms. Liam, a 17-year-old high-school senior from Connecticut, has had HPPD since his first LSD trip. He worries that HPPD can risk blending into obsessive-compulsive behaviour, with sufferers unable to look past or ignore their disorienting new condition if they’re untrained in how to relate objectively with their thoughts. “The off-product in my vision became something I constantly noticed,” he says.

Alienation is a natural effect of HPPD. While everyone else is feeling perfectly ordinary, the sufferer can be locked in their own private Alice in Wonderland. It’s hard feeling so different. The problem is worse in more vulnerable occupations. Mark, whose “brain felt plain damaged”, was especially keen to conceal his identity. He works as a school teacher.

For Kalen, a 31-year-old from the Bay Area in California, HPPD and its comorbid symptoms – especially dissociation and low-level psychosis – left him unable to hold down friendships for five years. “The grief you suffer in no longer feeling like you have an identity, especially one tied to a certain group of close friends, is truly unbearable. Every day feels like mourning the death of a loved one, but with HPPD that loved one is you.”

Kalen couldn’t keep it from his family, he says, but “nobody really understood the magnitude of what had happened – including myself”.

Alcoholism is a big problem for HPPD sufferers. Since alcohol can briefly reduce the symptoms, the bottle can be a tempting escape for extreme cases. For years, Jay – the Glastonbury tale – would get “blackout drunk three-to-four times a week”.

If you’re an end-of-life cancer patient looking to reduce your anxiety about death, the weight you place on developing HPPD will probably be fairly low

With depression, anxiety, alcoholism and psychosis all risk factors for suicide, it takes only one step to assume that HPPD can kill. I ask Jay if he knows of any suicides in the community. “Yes, heartbreakingly several members have killed themselves due to suffering from HPPD. I have also known several people drink themselves to death trying to ease their pain.

There are thousands like Jay, Kalen, Mark and Liam. But no matter how tragic their experiences, you might assume that HPPD is a condition too rare to pay much mind. The risk may be real, the argument goes, but that’s no reason not to trip – and especially when the benefits of a psychedelic experience can be so fruitful.

Indeed, despite forging a career on their downside risks, even Dr Abraham is open to the integrative potential of psychedelic drugs. Sometimes the “cost-benefit analysis” will be fairly plain, he suggests. If you’re an end-of-life cancer patient looking to reduce your anxiety about death, the weight you place on developing HPPD will probably be fairly low, or at least compared to someone young and healthy. This is all well and true. What many won’t realise, though, is that the cost side of the equation may be higher than one first assumes.

A 2011 survey of 2,679 users of psychedelic drugs (executed in collaboration by psychiatrists at the University of California, Berkeley and the drug education website Erowid) found that 4.2 per cent developed HPPD so impairing that they considered medical help. The figure is used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, or the DSM, which serves as a field guide for psychiatrists in diagnosing mental illness.

The study is by no means authoritative. Yet even within a band of uncertainty, a figure like 1 in 25 will show up significantly in a big population. In the UK, for example, the share of 16-24 year olds who took hallucinogens and/or MDMA in the last year rose from 5.5 per cent to 7 per cent from 2010 to the end of 2018 (the latest period with available data): a change that translates to a more than 25 per cent increase in under a decade. Taking population data from November/January 2018/19, 7 per cent amounts to at least 486,500 16-24 year olds having taken a major HPPD-risking drug in the last year.

To give the benefit of the doubt, we could focus solely on hallucinogens such as LSD and magic mushrooms, which pose a higher risk for developing HPPD. Even then, however, we’re still left with a minimum of 150,000 users. And if the 4.2 per cent figure is anywhere near accurate, this is a clear cause for concern.

We were shocked that between 40 and 50 per cent of the kids who took hallucinogenic drugs had some kind of unbidden visual disturbance up to a month after the trip

Whatever figure we produce, it may well be an underestimate too. The number wouldn’t account for those at 25 and above (or younger than 16 and at even more risk), or those whose symptoms are real but not impairing enough to warrant a visit to the doctor. Most obviously, it only measures one year: even within the same 16-24 year age group, some portion will have been hallucinogen users in every applicable year up to 2018-19, and therefore be potential sufferers of HPPD.

And 150,000 users doesn’t mean 150,000 trips. There’s every reason to suppose that some had taken a drug multiple times. Many will take a psychedelic once-a-month or every two weeks, and often in combination with cannabis and MDMA: two drugs known to amplify the risk. And if you’re fortunate enough not to fit in the one-to-10 trips bucket, every additional experience you accrue risks taking you to the next level and developing the disorder.

Even studies from the 1950s recognised lingering visual disturbances as a side effect. There’s reason to assume, then, that HPPD is an affliction for some in the older generation, many of whom may be reluctant to speak after six decades of relative normalcy.

Experimentation from the 1960s to the 1990s was, by all accounts, far more frequent – and far more reckless – than in the days since. Gathering accurate data from the time is practically impossible, but statistics from Monitoring The Future suggest that the share of American 18-year-olds sampling LSD at least once in the last year increased from 6.4 per cent to 8.8 per cent from 1976 to 1996, with lows in the 1980s still at between 4.4 per cent and a shade under 5 per cent. This would amount to thousands upon thousands of trips every year, and a likely leap in HPPD cases as a side-effect.

Could there be a hidden epidemic of baby-boomer and older millennial HPPD cases? Among the many millions who tried LSD in the 20th-century, would it be unreasonable to suggest that at least 1 per cent (and maybe more) still face serious HPPD symptoms to this day?

“It’s a good guess,” Abraham says. “I don’t think that’s off the mark.”

The rest of us

But what of the remaining 95.8 per cent who don’t suffer from impairing HPPD-like symptoms? What share would have faced effects that were noticeable but still not severe enough to visit a doctor?

Like everything HPPD-related, this question is under-researched. Precise estimates are not forthcoming. Yet the data we do have is slightly concerning. In the same 2011 study, just over 60 per cent of respondents reported seeing things “that resembled hallucinogen effects” after the drug had left the body.

Abraham conducted a similar survey of undergraduates in San Diego about their drug use. “We were shocked that between 40 and 50 per cent of the kids who took hallucinogenic drugs had some kind of unbidden visual disturbance up to a month after the trip. “I remember reading the data and thinking, ‘Holy mackerel. That’s really high’.”

These results can only be indicative. The nature of recreational use is likely to differ significantly from the more regulated setting of contemporary psychedelic research, for example. Dr Robin Carhart-Harris is a Research Fellow at Imperial College London. He heads up the college’s centre for psychedelic research, which has already published a range of well-received and promising studies on psychedelics’ therapeutic potential.

Compared to control groups who had never taken LSD, users without the clinical symptoms of HPPD still had to stand a metre closer to get the right answer. And HPD sufferers? Even closer

“In well over 100 participants and several hundred dosing sessions,” Carhart-Harris told me that one-third of subjects “report some lingering perceptual effects after the drug experience”.

These results partly replicate a 2010 study he conducted with Professor David Nutt, the ex-government drug tsar, on the perceived risks of psychedelic drugs. Surveying 626 recreational users, the authors found that 40 per cent reported moderate or severe visual after-effects, of whom 24 per cent thought the changes less-than-preferable (but still livable), and 6 per cent felt the changes “drove them mad”.

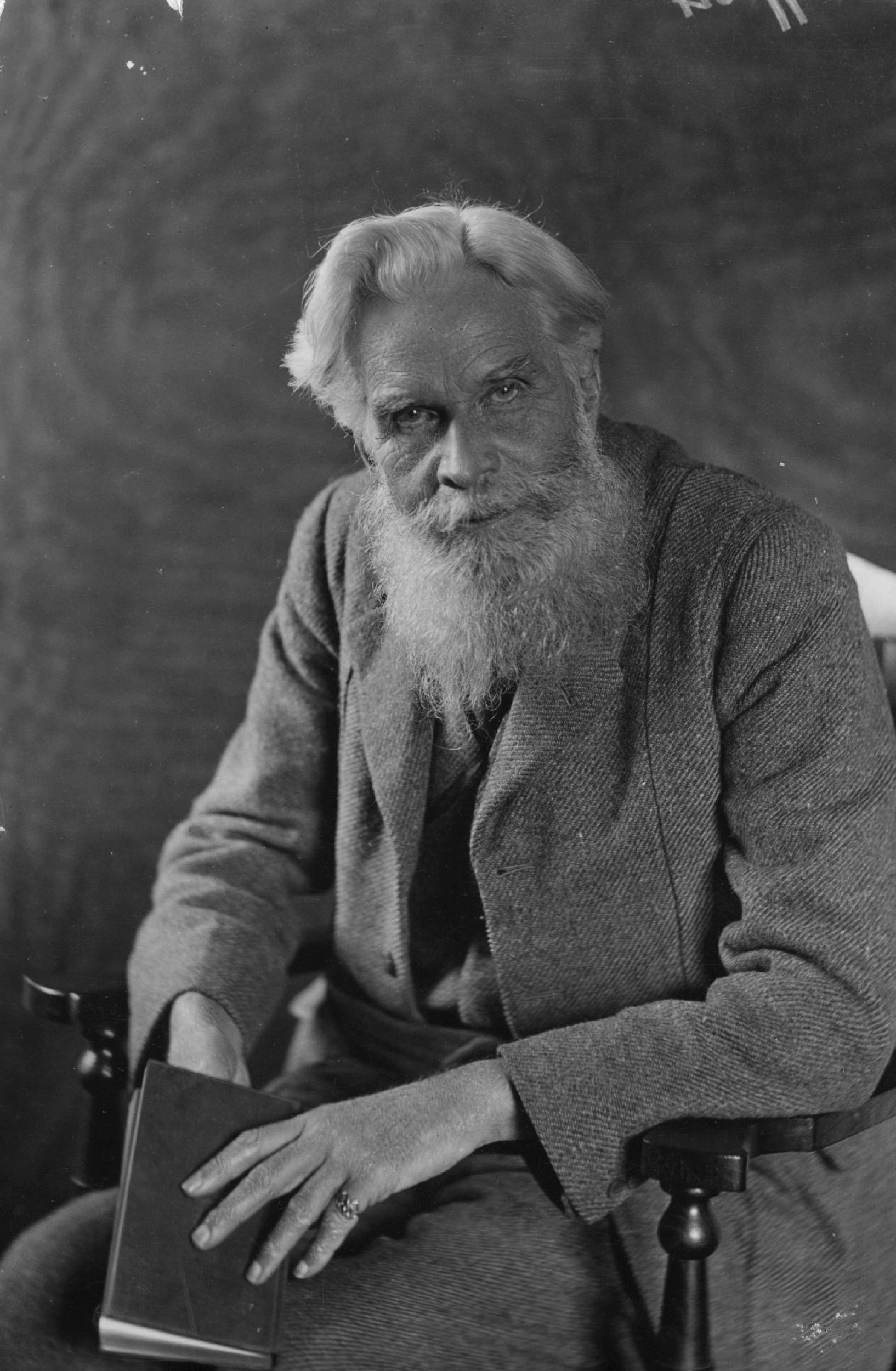

The “visual disturbance” for psychedelic users will most likely range in severity. At the lower end, it could consist in a simple reduction (or sometimes an exaggeration) of acuity or colour discrimination. In fact, in the first ever-recorded instance of a post-hallucinogen disturbance, the 19th-century scholar Havelock Ellis noticed that he was “more æsthetically sensitive than [he] was before to the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and colour” following an experiment with mescaline.

Changes in colour perception have been attested clinically. While first researching the condition in Boston in the early 1970s, Abraham performed a series of experiments on people’s ability to discriminate between shades of white and yellow. He pinned a phone book picture of a silhouetted cowboy on the wall and asked his subjects to describe the colour of the sun at varying distances.

Compared to control groups who had never taken LSD, users without the clinical symptoms of HPPD still had to stand a metre closer to get the right answer. And HPPD sufferers? Even closer.

Whether the disturbance ever exceeds a temporary dent to eyesight is an unknown. Many may face the visual snow, after-images, tracers and haloes with some richness, and yet never exceed the “subclinical” ceiling required to be an HPPD sufferer. Drawing any serious conclusions about psychedelics’ lingering impact will only take more research.

The research challenge

Getting reliable HPPD statistics will always be a challenge. One problem is a sheer lack of awareness among medical professionals. Before and beyond HPPD’s codification in the 1980s, Abraham explains that he would be the fifth person sufferers would turn to for help. The first would be their primary care doctor; then an ophthalmologist; then a neurologist; then a neuro-ophthalmologist; and then a psychiatrist.”

Even in the early 1970s, when cases of LSD-related mental illness were at a spike following the first psychedelic revolution, HPPD sufferers were apparently cast aside. “No one really had an interest in them but me, because they’re kind of benign and mild,“ Abraham says. ”They came in and said, ‘Doc, what’s wrong with me? I’m seeing trails!’ And if you’re a hardworking psychiatrist and psychotic people are jumping out of windows, a guy waving his hand in front of his face isn’t gonna get your attention.”

This was a problem that Jay experienced first-hand. LSD and magic mushrooms were being used more than ever before in the mid-1990s, and presumably cases of HPPD were multiplying at the same time. But Jay’s doctors had no idea what to do. “My GP didn’t really want to know and just put it down to depression. I was put on Prozac and this made me seriously ill.

“My anxiety and depersonalisation/derealisation (disorders with symptoms of dissociation from the body and the environment) were trebled in the space of a few days and left me close to suicide. I ditched the pills and didn’t seek out any medical advice for another decade or so. Thankfully, I found a neurologist who had experience with HPPD and other drug-induced disorders.”

Jay may have been one of the lucky ones. Owing to their hallucinatory symptoms, as many as half of Abraham’s patients had been misdiagnosed initially as schizophrenics, which led some to crippling dead-ends on anti-psychotic drugs. He recalls a patient who took their own life because the life-draining effects of his medication were so extreme. Others would never find Abraham at all, their fates unknown and undocumented.

I have this problem. I know I caused it myself. I feel guilty about it. I feel ashamed. I’m gonna talk to Dr X or Y and they don’t know anything about it, either. It’s not killing me. And so I will just keep it to myself and not go public

Psychiatry has evolved a lot since then. Does this kind of misdiagnosis really still happen? “Oh yeah. Absolutely,” Abraham says.

The second problem is the patient. Being Class A-classified in the UK and Schedule-1 in the US, psychedelic drugs are still broadly stigmatised, and some observers will see a self-inflicted injury like HPPD as unsurprising at best or deserving at worst. “‘I have this problem. I know I caused it myself. I feel guilty about it. I feel ashamed. I’m gonna talk to Dr X or Y and they don’t know anything about it, either. It’s not killing me. And so I will just keep it to myself and not go public.’ I have had many cases like that,” Abraham recalls. The result: a further constricted pool for research, untreated symptoms, and an ever-vicious cycle that escalates both.

The psychedelic problem?

One potential problem with HPPD research will be perhaps more controversial. Abraham – and some HPPD sufferers I spoke to – place part of the blame with the psychedelic community itself. Defining a discrete community with so many disparate and sometimes-irreconcilable groups will be a fool’s game, granted. But if we mean proponents of psychedelics – be they researchers, Goa ravers, spiritualists, microdosers, rockers and everyone in between – a hardline element may overlook or minimise the risks.

Earlier in his career, Abraham remembers proponents leaving meetings, dismissing studies or engaging in outright denialism. So they claimed it was bogus? “Oh, yeah. Absolutely... Watching them dance round this collection of data…,” Abraham trails off. “Why not just say it’s real and move on?”

In my own research, the community was unfailingly open. One of the administrators of Reddit’s LSD group, for example, was more than supportive in linking me up with sufferers of HPPD and raising the disorder’s profile. Some psychedelic scientists are far from dismissive, too. Carhart-Harris, who heads up the psychedelic research centre at Imperial, issues specific warnings about HPPD to test subjects before they sample a drug, and has himself executed research into lingering visual effects.

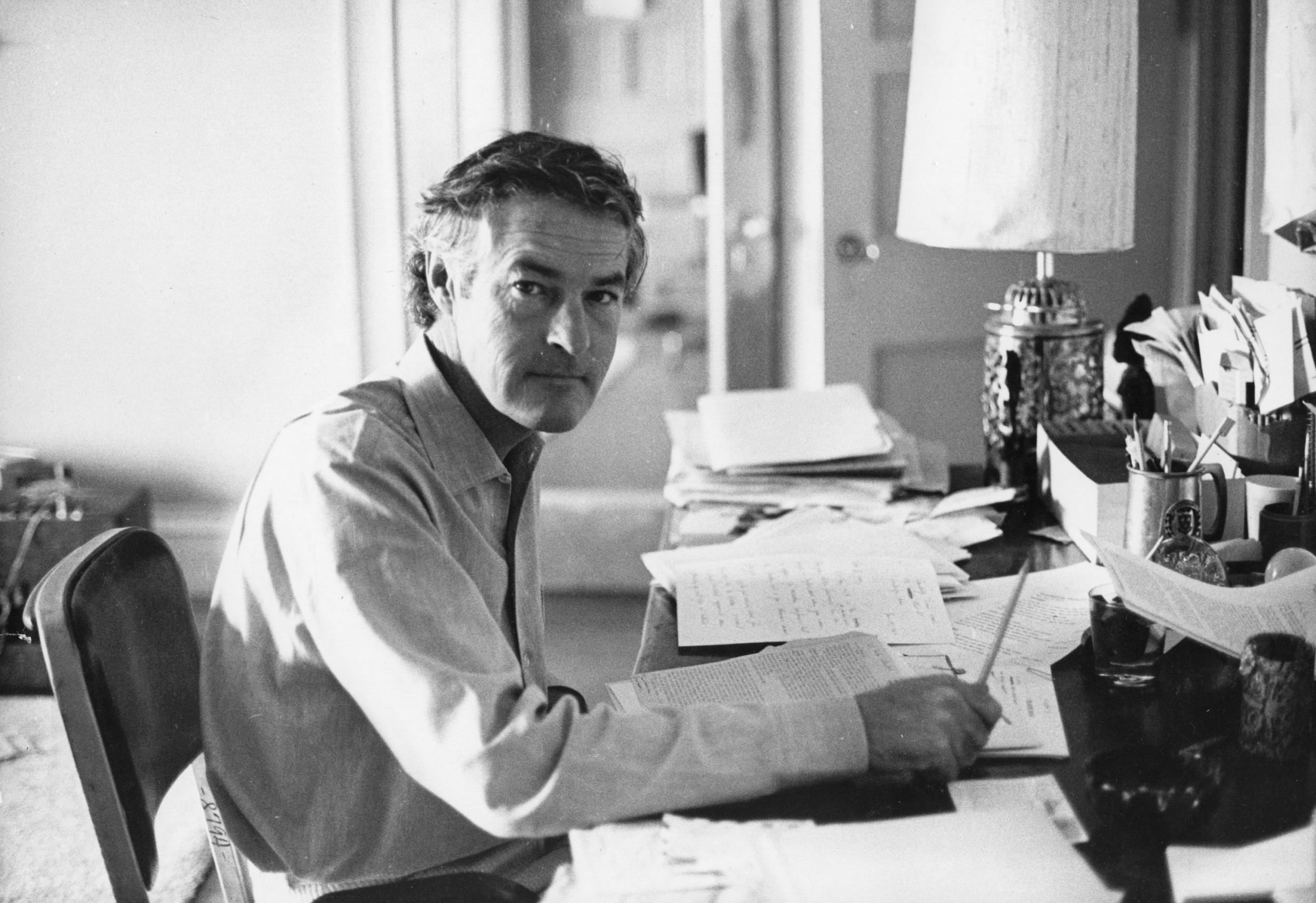

Don Lattin is a big brain in the community. He’s written a trilogy of books on the history of psychedelic drugs, ranging from the early days of Dr Timothy Leary to the clinical advances of the present day. In an afterword to the Harvard Psychedelic Club, the first of the three, Lattin describes openly his own terrifying experience with the disorder. News anchors looked like monsters, cars were the height of buildings, and Lattin worried seriously that his LSD experiment had induced permanent psychological damage.

But no matter what team a sufferer may be on, the more upfront they can be about their experiences the better off we’ll be in reducing harm and making inroads for treatment.

Ultimately, then, there’s no reason why HPPD should conflict with psychedelic progress at all. They could even be allies. That HPPD exists and may affect the subjects of research should be cause for further investigation. The greater promise psychedelic drugs show in the lab, the more impetus there should be behind a clear and conscious examination of their risks. In fact, as a genetic disorder, Imperial’s Carhart-Harris agrees that future studies and prescriptions could screen for HPPD-susceptible users if the right technologies were developed.

HPPD affects our legislative approach, too. Drugs are criminal because of their ill-effects. And without a fleshed-out study of these ill-effects – their origins, likelihood and contours – we’ll have little backbone for our policy. If HPPD is more common than we assumed, this may be a good reason to put the brakes on any agenda for legalisation or perhaps further therapeutic research. Yet if early indications of its frequency turn out to be exaggerated, MPs will have to think deeply about why psychedelic drugs are illegal in the first place.

HPPD awareness is on the up. Discussion groups like the HPPD community on Reddit or HPPDonline – which together have more than 21,000 members – provide a valuable and sometimes life-saving space for sufferers to talk through their symptoms, vent frustrations, discuss emerging research, and stand as willing subjects for articles exactly like this one.

Some are even taking the agenda into their own hands. One patient – a prominent member of HPPDonline – has founded the Neurosensory Research Foundation, a 501(c) registered charity in the US. A benefactor for research and a pressure group for greater awareness, the foundation is making active calls for donations and forging important links with members of the academic community.

So: to address the title, what does happen when LSD never wears off? It’s not always pretty, that’s for sure. But the more we find out and the more we acknowledge, the closer we might come to finding the real answer.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress and isolation, or are struggling to cope, The Samaritans offers support; you can speak to someone for free over the phone, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

For services local to you, the national mental health database – Hub of Hope – allows you to enter your postcode to search for organisations and charities who offer mental health advice and support in your area

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments