How a presidential shooting changed the law on mental illness in America

Senator Dan Quayle claimed the insanity defence ‘pampered criminals’. Senator Strom Thurmond agreed, saying it gave criminals a ‘free ride’. The act of abolishing it should frighten us all, says Ed Prideaux

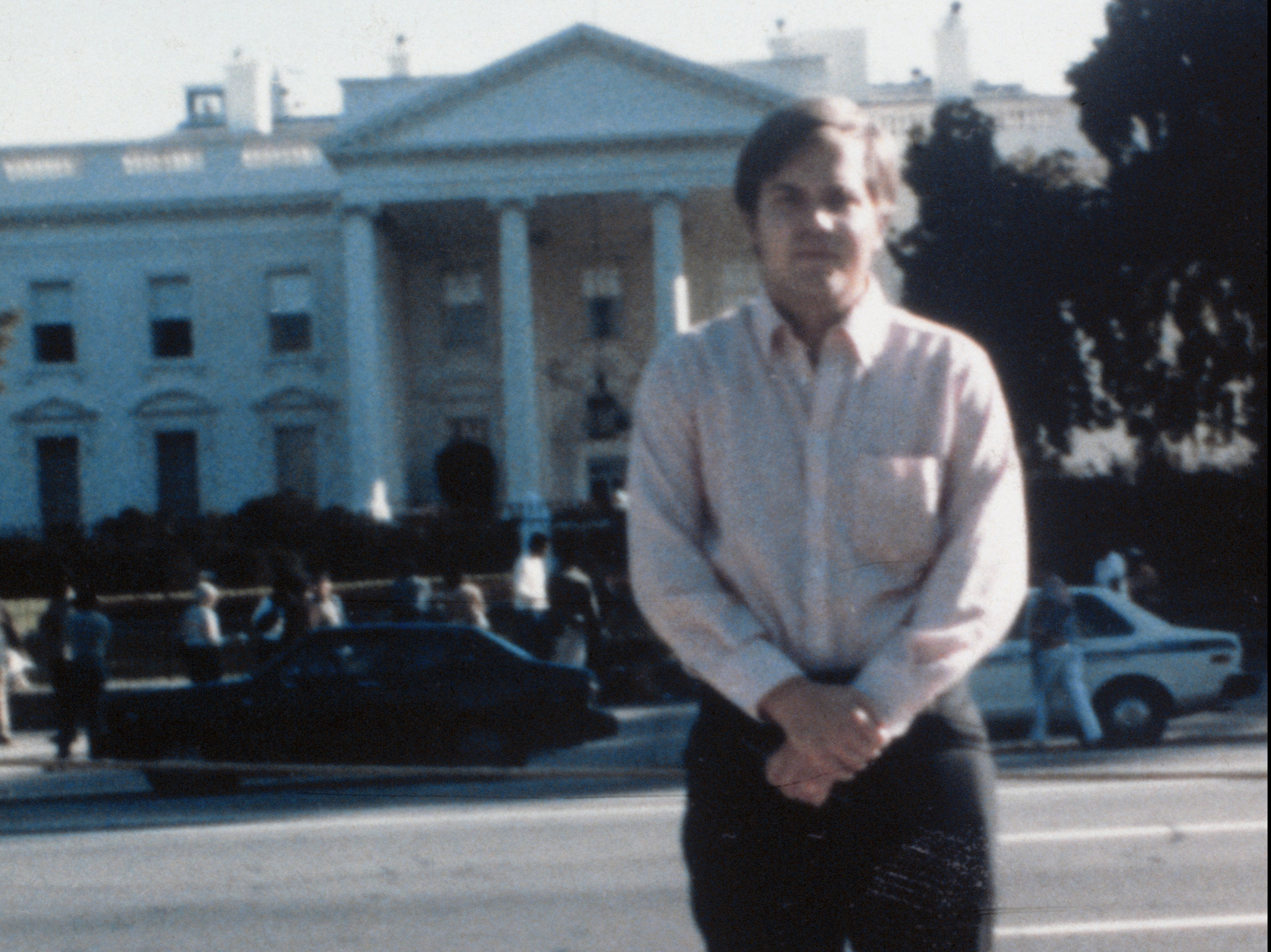

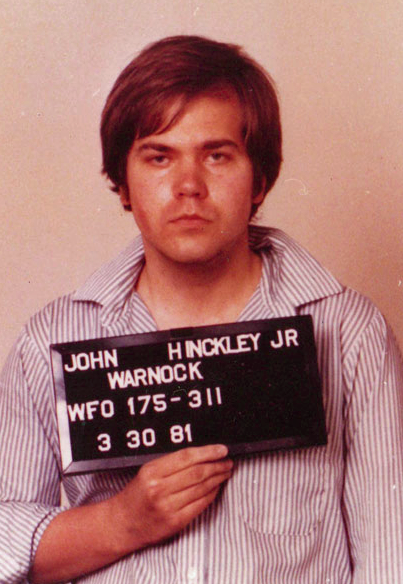

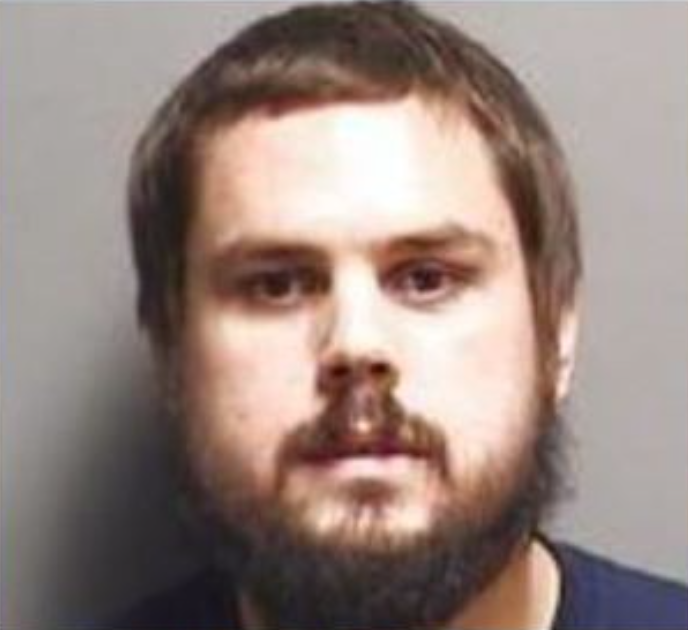

John Hinckley Jr was 25 on 30 March 1981. It was a big day for him. After a long ennui, things had begun making sense when he first saw Taxi Driver, the 1976 Scorsese film, at a cinema in Hollywood. He watched it over and over. Hinckley saw much of himself in the film’s main character: a traumatised, depressed Vietnam veteran played by Robert De Niro.

He bought an army jacket to look just like him. He took selfies with guns and played Russian Roulette. Most significantly, Hinckley fell head-over-heels with the film’s teenage co-star, Jodie Foster – no doubt the love of his life, he concluded – but something big was needed to tip the scales.

“This letter is being written only an hour before I leave for the Hilton Hotel,” he scribbled. “Jodie, I’m asking you to please look into your heart and at least give me the chance, with this historical deed, to gain your respect and love.”

Pistol-in-hand, John Hinckley booked a cab to the Hilton, where Ronald Reagan – just three months into his presidency – was due to speak. It’d be his last day as a free man for several years.

Read More:

Michael Putzel, a reporter with the Associated Press, was at the Hilton already. “I picked a spot as close as I could to the limousine because I thought that I’d have a better chance of getting my voice heard,” Putzel recalls. “The door opened and Reagan stepped out and waved to the crowd… As soon as the door opened, I got a good view of him and I shouted, ‘Mr President! Mr President!’ and a woman’s voice also shouted out something.

“And just at that moment, there was a pop! pop! pop! pop! pop! pop! – just like that. I instantly knew it was gunshots. A lot of people say [it sounds like] firecrackers, but these were not firecrackers. I had a fair amount of experience with gunshots. I knew what was happening.”

Putzel remembers the screams. “Almost instantly there were guns everywhere. Secret Service men all around Reagan had drawn their weapons.” He dashed to the closest phone and swiftly dialled in the news – his mind a motor, running on cortisol – and then returned to survey the scene.

Jim Brady, Reagan’s press secretary, was shot in the head and lying face-first on the pavement. He’d survive but never walk again. Thomas Delahunty, a local police officer, got a bullet to the neck and suffered permanent nerve damage. Tim McCarthy, a secret service agent who’d stepped in the line of fire, took a shot to the abdomen.

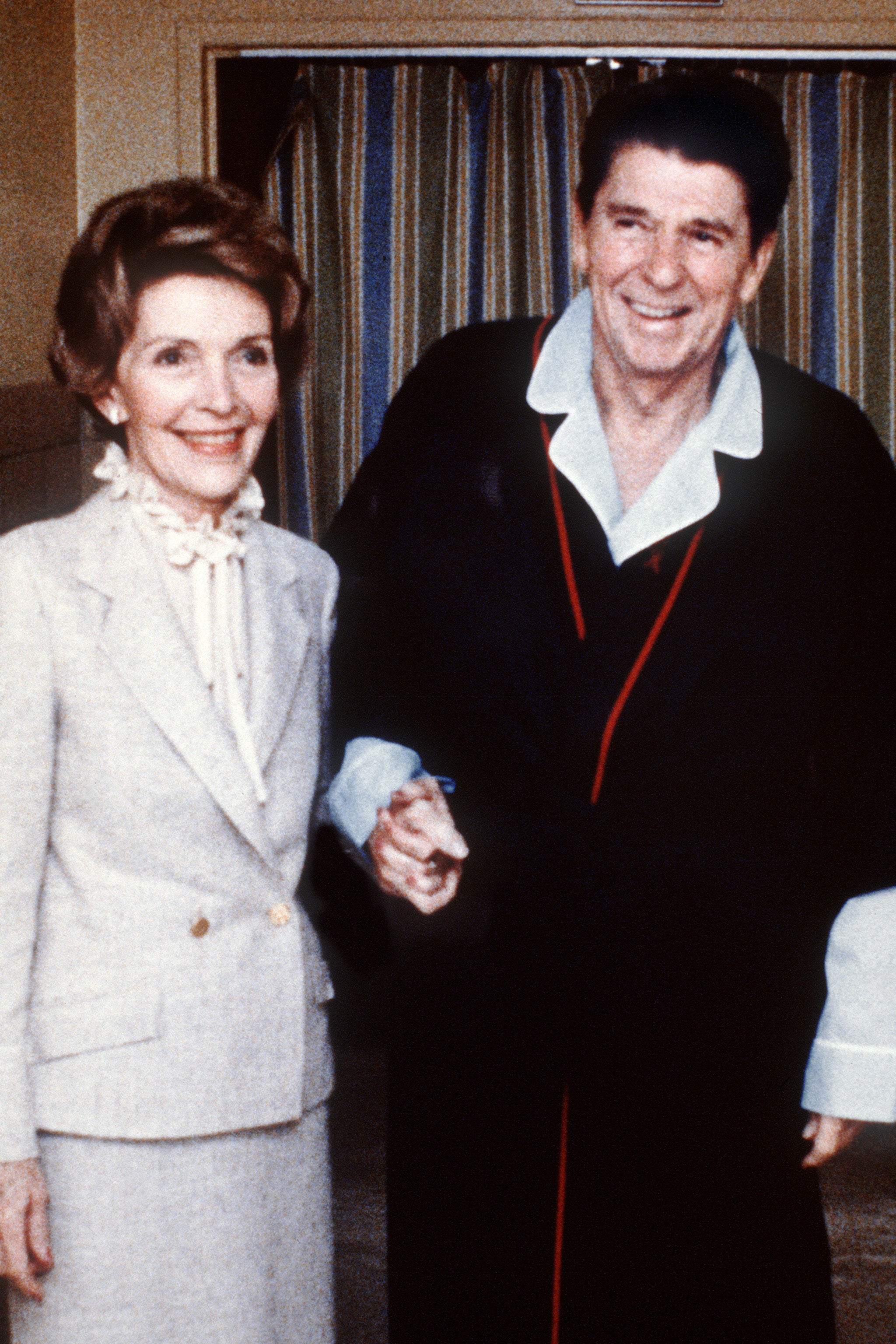

Hinckley, meanwhile, was buried in a scrum of security staff. On route to George Washington University Hospital, President Reagan was fighting for his life. A bullet had ricocheted off the limousine and punctured a lung, causing massive internal bleeding. Blood poured from his mouth: bright and red, oxygen-dense, and time was running out.

They made it. Reagan lived and his approval ratings leapt. Soon enough, news of Hinckley’s bizarre motive – to secure and confirm the love of Jodie Foster – hit the press. America’s collective psyche raised an eyebrow.

A court-appointed psychiatrist declared Hinckley fit to stand trial. He’d face judge and jury the following year. His millionaire Texan parents, JoAnn and John Hinckley Sr, pressed him to plead insanity. At its most basic level, the insanity defence is rooted in the M’Naghten Rules, which permit acquittal when the accused doesn’t know at all the “nature and quality of the act” or whether and why it was wrong. They’d been worried about John for a while. They should have seen this coming, they thought. They shouldn’t have cut him off.

Will Carpenter, a world expert on schizophrenia, was one of two psychiatrists hired by the defence to evaluate Hinckley. Carpenter would spend 45 hours in conversation with him and those he knew. As opposed to government psychiatrists, who saw Hinckley as an overprivileged, odd, selfish, but still sane, young man, Carpenter was swiftly convinced of something more serious. He had “a long history of inadequate development, a lack of motivation, except when he’s focussed on false ideas that played out with him”. When it came to Jodie Foster, “he wanted me to understand the relationship they had and why he wanted that to be known. He was very glad to talk about that”.

David Bear, the other defence psychiatrist, would spend 60 hours with Hinckley. He remained “absolutely embedded” in his fantastical love affair, Bear recalls, and the strange, blended world of Taxi Driver and heroic daydreams reigned unfettered on his mind. Bear remembers Hinckley’s “flat affect”: the poverty of expressed emotion, his unmoving face.

Hinckley’s fixation on Foster persisted in the courtroom. No Foster, no collaboration, and the actor was reluctantly brought to testify

Hinckley’s fixation with Foster persisted in the courtroom. No Foster, no collaboration, he told his defence team, and the actress was reluctantly brought in to testify. Clarifying that she and Hinckley had “no relationship” whatsoever, Hinckley grew incensed and hurled a pen, forcing his restraint and removal by security staff.

On a scheduled visit in May, Bear noticed something was up. He found Hinckley “lethargic and uninterested in talking, even about Jodie Foster”.

“I asked if he was feeling sick. He first told me that his stomach was upset, and he felt sleepy,” before admitting – again without any emotion, Bear notes – that he’d taken a toxic overdose of paracetamol, having stored the tablets secretly over several weeks. He tried to hang himself later that year. A brain scan showed Hinckley’s “sulci”, grooves found in the cerebral cortex, were unusually widened, characteristic of the abnormal neurophysiology of several mental disorders. Bear and Carpenter diagnosed him with schizophrenia.

The prosecution continued to deny Hinckley’s mental illness. His problem was narcissism, government psychiatrist Park Dietz told the jury, just like Hollywood stars. His vision of Reagan as a “cardboard figure” suggested more a lack of scruple than truly disordered thinking, the prosecutor added. Yet the jury was unconvinced. Hinckley was acquitted by reason of insanity and committed to an indefinite stay at St Elizabeth’s, a psychiatric hospital in Washington DC.

The acquittal provoked a wave of public outrage. A poll conducted by ABC News suggested that 83 per cent of Americans felt “justice had not been done”, and Foster was “horrified”. While the overwhelming response from his clients and colleagues was supportive, defence psychiatrist Bear received “some very angry letters” from members of the public. “One letter said, ‘I hope someday a member of your family is shot and injured for life or killed. And then you’ll know how bad this [verdict] was.’ It was a terrible thing to read and a total misunderstanding of what was going on.”

I hope someday a member of your family is shot and injured for life or killed. And then you’ll know how bad this [verdict] was

Politicians were quick to join in, some with aims well beyond Hinckley. Within a month of the trial’s conclusion, committees of the House and Senate held hearings regarding use of the insanity defence altogether. While a mainstay of Anglo-American justice for hundreds of years – it even dates back in some form to Ancient Rome – senator Dan Quayle claimed the insanity defence “pampered criminals” and deemed Hinckley’s verdict “decadent”. Senator Strom Thurmond agreed, spreading fears that the defence marked a “free ride” for criminals.

There’d been suspicion of the insanity defence for some time. To the public mind, despite their rarity and frequent failure, insanity defences spelled a literal “getting away with murder”: a toxic combination of credulous psychiatrists, cunning defendants and cushy hospitals, ripe for use and abuse. Suspicions synergised with the paranoid feeling of the times. Disorder was on the rise and front-page news was frightening. “Tough on crime” was a dogma. Even Hinckley’s Taxi Driver fell in the mix, projecting a New York City overrun with “low lives” and lower morals.

Myths persist. In a 2007study, college students estimated that the defence is used in 30 per cent of criminal cases and succeeds 30 per cent of the time; true figures suggest overall respective use and success rates of 1 and 0.002 per cent. The media doesn’t help, either, and especially with a case as political and bizarre as Hinckley’s.

In a review of articles about the insanity defence in American magazines between 1979 and 1988, more than half were published at the height of Hinckley’s trial from 1981 to 1982. “Those cases, where an ‘egregious criminal’ pleads insanity, tend to make the front pages of the papers or lead the local news broadcasts,” says Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at New York’s Columbia University. “When that defendant is almost inevitably found guilty, that’s on page 17 of the local paper.”

Against this backdrop, Hinckley tipped a crucial balance. The White House wanted scalps. The result was Congress’s Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984, which significantly constrains plea terms to this day in federal cases. Defendants can no longer excuse a crime on “irresistible impulse” – that is, they could not control their actions even if they knew they were wrong – and a mental illness should be both persistent (“temporary insanity”, including fleeting psychoses, is ruled out) and “severe” enough (albeit severity is ill-defined) to render the accused “unable to appreciate” the crime, where before it had allowed for lacking the “substantial capacity” to appreciate.

Most explicitly, it nudged the insanity defence’s burden of proof towards the accused, marking the only element of a criminal trial where the onus lies in favour of the prosecution. That is, the defendant must prove that they’re insane, rather than the prosecution proving they’re sane. The change attracts mixed opinions. Where some deem it a re-balance, Ann Krin, the chair of psychology at the University of California Berkeley, calls the change inconsistent “with the constitutional requirement that people are considered innocent until proven guilty”. The change is weighted, too. Because of popular myths surrounding its use (and apparent abuse), the insanity defence always faces an “uphill battle” in courtrooms, regardless of the accompanying norms.

More important than federal changes, though, was what the act and Hinckley’s case inspired in America’s states. In the three years after the Hinckley acquittal, half the states – in whose own jurisdictions most of America’s crimes are tried –narrowed their defences. Most replicated the Reform Act, but four states took it a lot further. In the immediate aftermath of Hinckley, Utah, Kansas, Montana and Idaho would abolish the insanity defence altogether. A basic legal right lies absent from state books.

Why a state would abolish their insanity defence seems initially puzzling. However, coloured by public myths, the insanity defence underpins our very ideas of justice and personal blame. Proponents of abolition claim that doing away with the defence “improves the criminal justice system’s public image”, and ensures trust by holding “the mentally ill accountable for their actions the same as everyone else”. But for Richard Bonnie, a professor of medicine and law at the University of Virginia, such a claim marks a contradiction in terms. The defence prescribes precisely the limits of how we judge and ordain one’s responsibility for an act. We don’t punish those who didn’t know what they were doing.

Principle collides with real life. In Boise, Idaho, John Joseph Delling was only 21-years-old when he killed his close friends. Drawn from a family with a history of mental illness, Delling suffers from paranoid schizophrenia, with symptoms including hallucinations, delusions and disordered thinking. Nearly a quarter of Idahoans are living with a mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, of whom nearly six per cent live with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

In late March and early April 2007, amid a florid psychotic episode, Delling became convinced that several of his friends were stealing his “aura” and siphoning away his psychic powers. He drew up a list of all those destroying his brain, and resolved to act soon to protect himself. The resulting shooting claimed the lives of two people. Delling was charged with first-degree murder. Both prosecution and defence agreed that Delling was psychotic. Even the judge conceded that his “crimes did arise directly from his illness”, and that “he was in such a severe grip of his delusions that he could not have conformed his conduct to the law”. It didn’t matter. The only way to mitigate for mental illness in Idaho – its defence deleted in 1982, in the wake of Hinckley’s case – is in the narrow domain of mens rea, which is the legal term for “guilty mind”.

The Supreme Court has already issued landmark rulings banning executions for the intellectually disabled and children

In other words, Delling’s team had to prove that his illness disrupted his intent to kill his friends as human beings. Yet rather than negate his intention, Delling’s psychosis precisely “gave him reason to form it”. According to Stephen J Morse, a legal scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, separating the insanity defence on the basis of “cognitive capacity” and “moral capacity” – with the abolished states allowing only for the latter – will always make little conceptual sense.

“Both are cognitive questions,” he writes, and “they differ only in the object of the knowledge required”: Delling’s moral compass may have been warped and “distorted” by psychosis, but in his private world it remained “perfectly intact”. Doing nothing would have left him without a brain. He had to act.

Odom worried that a conspiracy of Martian invaders was taking over people’s bodies. He shot and nearly killed a local pastor, whom he believed to be a secret Martian

Delling’s defence was left in the lurch. His case was taken to the Supreme Court, which declined to give it a hearing. Despite the insanity defence’s historic basis in common law – and constitutional rights to due process and protection from “cruel and unusual punishment” – the court affirmed Idaho’s right to make its own policy. Delling was handed a life sentence, and reportedly remains housed in solitary confinement at a maximum security jail. He’s one of 4,000 inmates with severe mental health problems in isolation at US prisons.

Isolation is especially dangerous for schizophrenia patients, warns Will Carpenter, Hinckley’s psychiatrist. Lack of social contact erodes the grounding needed to avoid delusional thinking. Standard prison life is largely ill-suited to those with mental illness, too, who all in all make up around 37 per cent of the US prison population. Studies suggest that mentally ill inmates fail to adapt to incarceration “on every measure of psychological adaptation”, which “manifests itself in significantly higher rates of disciplinary infractions and suicide rates”.

A similar case hit Idaho headlines in 2016. Kyle Odom, a promising biochemist and military veteran, lapsed into psychosis after a powerful dissociative experience in meditation. Odom worried that a conspiracy of Martian invaders was taking over people’s bodies. He penned and published a manifesto, in which he declared himself “100 per cent sane, 0 per cent crazy”, and sent it to media outlets and the White House. He shot and nearly killed a local pastor, whom he believed to be a secret Martian. Again, though, Idaho’s insanity laws meant that Odom was unable to issue a plea. He was sentenced to at least 10 years behind bars.

Proponents of abolition claim that key protections are always in place. Kansas and Iowa, for example, run mental health courts, which divert offenders from the mainstream prison process. Not only do Idaho and Montana – the two other abolitionist states – lack such courts, but they’re directed exclusively at low-level offences such as jaywalking and shoplifting, not murder.

Still, in Idaho like any other, defendants must first demonstrate their competence to stand trial. If mentally ill patients are unable to understand court proceedings and assist their attorneys, they can sidestep the penal process altogether. Issues of competence delayed the trial of schizophrenia patient Timmy Kinner, who stabbed a three-year-old girl to death at an Idaho birthday party in 2018. Once competence is restored, though – which, in Kinner’s case, took several months, with initial evaluations describing “dangerous” levels of mental illness – the obstacles remain the same. He will face a death penalty trial some time this year.

Executing the mentally ill goes well beyond the abolished states, too. Among those with capital punishment, only Ohio has banned the practise, and the Death Penalty Information Centre lists at least 23 convicts executed since 1999, with incapacities ranging from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder to PTSD and dementia. For Shaakirrah Sanders, a professor at the University of Idaho’s College of Law, closing the window on capital punishment could be a crucial first step away from abolition. The Supreme Court has already issued landmark rulings banning executions for the intellectually disabled and children, both of whom are exempt for reasons “very analogous to severe mental illness”.

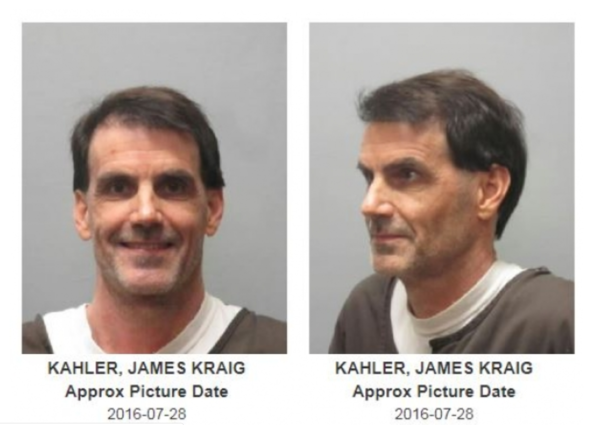

In a trial compliant with state rules – and endorsed by a Supreme Court ruling – Kahler was barred from admitting evidence of his mental illness before the jury. He faces the death penalty by lethal injection

In challenging abolition directly, however, the courts prove a cumbersome route to change. Charged with safeguarding the letter of the Constitution, which does not directly mention the insanity defence, majority verdicts have claimed consistently that states are within their rights to define the defence however they like. Just last year, in a verdict on Kansas’s abolished insanity defence, the Supreme Court again confirmed its indifference. The case centred on James Kahler, a long-time sufferer of “extreme depression”, who claims his condition went psychotic before killing almost his entire family in a mass shooting. In a trial compliant with state rules – and endorsed by Supreme Court ruling – Kahler was barred from admitting evidence of his mental illness before the jury. He faces the death penalty by lethal injection, along with nine others in Kansas’s El Dorado Correctional Facility.

“In conclusion, [since Kahler] it is now constitutional to effectively abolish the insanity defence,” wrote Stephen J Morse. “No state has done so, however, since the original four states did so decades ago. One hopes that no further jurisdictions will follow these examples.” The ossification of America’s insanity defence is cause for worry and relief. Whether abolished states will ever revise their policy – restoring the rights of mentally ill defendants to their historic precedent – is uncertain.

In Utah, a 2020 bill that challenged abolition, drafted by Democratic lawmaker Carol Moss, was defeated in the state legislature. Critics peddled fears it would “open the floodgates” to a wave of resource pressure on mental hospitals. Most shockingly, concerns were shared, Moss claims, over the resulting loss of revenue from mentally ill patients no longer heading to standard prisons. The envelope calculation, practically picked from thin air, was put at around $100,000. Money talks.

The bill began with the case of Rob Liddiard, who was convicted and handed life without parole for killing his parents in 2017 during an unmedicated psychosis. Less recently, Tomas Herrera, a schizophrenia patient, killed his ex-girlfriend over fears she was a robot being controlled by the mafia. Because Utah runs a mens rea defence – he thought he was killing a robot, not a human being – Herrera was acquitted. The same couldn’t be proved for the others he killed, though: her mother and son. He was convicted of murder and eventually deported to Mexico, with his court challenge to Utah’s abolition dismissed.

After the Supreme Court’s Kahler ruling, a future high-profile case – especially one with the political colour of Hinckley’s – could spark a re-offensive. It certainly worries Paul Appelbaum, the Columbia professor, who points out that states “now more clearly have options’’ they might have lacked in the early 1980s, when the original reforms were effected. A new equation of federal change, White House backing, and state flexibility could prove dangerous. There have been close calls, too. In 2016, Michael Sandford, a young Briton struggling with obsessive compulsive disorder and psychosis, made an assassination attempt on Donald Trump during his election campaign. The attempt was largely nominal. He reached for a police officer’s pistol, 10 yards away from his target, got swiftly arrested, and even Trump made little political capital of the “feebly unsophisticated” plot.

Counterfactuals are worth considering. What if Sandford had come closer – or maybe pulled the trigger? What if, rather than in Nevada, it had taken place in an abolitionist state like Idaho? What if the shooting had occurred during Trump’s presidency, when he had the direct levers of executive power? What if the stars of Trump’s political plotting – the directed outrage and support of his voter base, the right precedents in the news agenda, a quick Twitter response – had lined up specially for a shock? And as Sayeeda Warsi pointed out, what if Sandford had been Muslim, opening the narrative for discussions of terrorism and extremism, or Bame?

Indeed, the tendency to over-react to high-profile incidents of mental illness is alive and well. Mass shootings, for example, are presented frequently as a function of ill health among their perpetrators. Proposals have been made for a registry of mentally ill patients, carefully tracked (to the tune of $100m) on measures of violence and gun sale. A policy of banning firearm sales among those making reasonably violent threats to their psychotherapists has been enacted in California. SSRIs and psychiatric drugs are blamed for driving shooters over the edge, prompting calls to retract or revise their prescription.

Suspicions of the insanity defence don’t exist in a vacuum, either. They amplify and relate intimately to the stigma, and visceral fear, surrounding severe mental illnesses

Yet there’s no convincing evidence that the mentally ill are any more likely to commit mass shootings at all. In the broader scale of gun-related violence in America, the idea of a “loner” mentally ill gunman is largely a media trope. The independent role of psychiatric drugs is, at best, hugely exaggerated and confused.

Suspicions of the insanity defence don’t exist in a vacuum, either. They amplify and relate intimately to the stigma, and visceral fear, surrounding severe mental illnesses. While severe mental illness is implicated in just four per cent of community violence – and schizophrenia patients are up to 14 times more likely to be the victims of crime than perpetrators – high-profile incidents like Hinckley’s have engendered a belief that violent incidents are common and expected.

Janice* is 33 and lives in the US. “It’s frustrating trying to navigate a world in which I, a small, timid woman with a fear of confrontation, am assumed to be a violent murderer,” she says. “I have absolutely noticed that people are scared of me. More than once I’ve gone to see a doctor for a physical illness or injury, and had a perfectly normal conversation with the doctor who comes to treat me.

“Then when they start reading my patient file, they gasp and/or visibly jump back from me as though I’m about to attack them at any moment. I also once had a guy I was interested in dating ask me whether I’d killed anyone!”

A study of 41 films featuring schizophrenia from 1990 to 2010 found that half its subjects displayed violent behaviour, and nearly one-third killed another character. By some measures, stigma towards schizophrenia in the US has risen in the last two decades, and all despite a growing awareness of mental health and neurodiversity. Research by Indiana University Bloomington’s Bernice Pescosolido suggests that by 2018, the share of survey respondents who over saw schizophrenia patients as “dangerous to others” had increased to over 60 per cent, and “44-59 per cent supported coercive treatment.”

Where there have been attempts to de-stigmatise, using cases like Hinckley’s as a starting point, risks bringing problems. Drake is 18 and lives in Michigan. “Most people that try to spread awareness of schizophrenia only show off the most extreme cases, those that are too terrified to function in the outside world and those that can’t control it and become violent.

“They try to defend our actions by saying that it’s out of our control, but that’s completely wrong. As overwhelming as the symptoms can be, it’s how we choose to react to it that people see. Saying it’s completely out of our control just demoralises me.”

Where schizophrenia does produce violence, albeit rarely, the independent role of mental illness is often muddied by recreational drugs and non-compliance with medication, both of which increase with patients’ experience of internalised stigma and distress. “I think the main problem with the media narrative is that it influences how strangers in all parts of society see us,” says Kasper, who’s 21 and lives in Copenhagen.

As a rule, family and friends are never to call the police on him, he says. A quarter of those killed in police encounters from 2015 to 2016 exhibited signs of mental illness. Research by the Treatment Advocacy Centre suggests that patients with untreated severe mental illness are 16 times more likely to end up dead. “I’m almost certain my diagnosis would lead to me being injured or killed. I’ve seen far too many cases of it happening when schizophrenics ended up being confronted by police, and I don’t want anyone I care about to end up with the guilt of feeling responsible for my death.”

These stigmas intersect with issues of racism. Black Americans face statistically more stigma, worse outcomes, and even lower-quality treatment in their first episode of psychosis than their white counterparts. The effect is replicated in the prison system, where black inmates are less likely to have their mental health problems identified and treated.

When it comes to Hinckley’s case, one can raise reasonable questions about its likely outcome today. No matter the terms of the defence, though, he’d always fare well compared to most. White, upper-middle-class and the child of millionaires, for the 1982 trial his parents hired Edward Bennett Williams, a defence lawyer known for defending gangsters and celebrities at extortionate fees. For their services in evaluating Hinckley, Bear and Carpenter were specially chosen and handsomely paid. “Compared to the usual reimbursement of psychiatrists, it was a phenomenally high rate,” Bear recalls.

“I was frankly shocked by the hourly rate and the kind of hotel rooms I was always given. There’s no question it’s a big problem.”

While government prosecutors hugely outspent the defence in Hinckley’s trial, I asked Bear what safeguards there are to ensure psychiatric testimony isn’t at all swayed by money. Reputation management, he describes: if you’re seen to compromise objective testimony for profit, then you lose credibility. Simple. “You better choose your cases,” he was advised. There’s a logic at play, but questions hang over how delicate this Nash equilibrium really is. It also says little about the more basic fact that richer clients can afford psychiatrists who may, in one way or another, provide simply better testimony, and raise their odds of trial success. Bear was Harvard-trained, Carpenter a world expert on schizophrenia.

They refused to believe that Mark had a mental illness. They thought [his illness] was drug use from his prior years.. They did not understand things

The fact of wealth and racial inequality in the insanity defence is among its critics’ more important arguments. Pro-abolition messaging dressed Hinckley’s acquittal as the fruit of paid-for justice. Joan Becker certainly wasn’t convinced. “At that time, I thought he got away with something. Because I didn’t understand the illness. So I thought, ‘Wow, he got off pretty light.’ But again, uneducated person here. [I] didn’t understand the illness.

“But then as the years went on and I heard ongoing stories about this treatment [and its success], I was so thankful for him to have the ability to be back with his mother. It’s exciting to me, as a mother with a son with that illness.”

Hinckley was released in 2016: 35 years after the shooting, and 31 years after psychiatrists first reported his condition to be in considerable remission. Critics claim insanity acquittees are typically held for far longer than necessary for treatment, putting aside those interned for whole-life terms. What’s more, Hinckley’s decades inside were under near-constant surveillance from the Secret Service, who were charged with monitoring for an ongoing intent to kill political figures. Hinckley made it out, though. Since last year, he can even post his artwork online and live independently. But Joan Becker’s son will never breathe free air again.

Mark Becker was 24 when he killed his high-school football coach, Ed Thomas. Thomas was Satan, Mark believed, and he was hurting people. He was raping Mark and sending him telepathic messages. He had to be stopped. Becker, off medication and a long-time paranoid schizophrenia sufferer, shot Thomas in the school weights room. Mark was charged with first-degree murder. He and the defence team had to grapple with Iowa’s penal system, which – while not abolitionist – runs a narrowed insanity defence. Iowans are also prone to the myths Hinckley’s case may have advertised.

“It was a huge televised event. It was a lot of pressure on those jurors. But what it came down to is, the jurors asked the judge a question regarding what would happen to Mark if it was ‘not guilty’ – and the judge refused to answer that question,” says Becker, who put Mark’s story in a 2015 memoir, Sentenced To Life. “Our jurors are not educated.

“They refused to believe that Mark had a mental illness. They thought [his illness] was drug use from his prior years... They did not understand things. They believed that if they said not guilty, then Mark would walk out of the courtroom that day.

“Many people think it’s just very easy to say, ‘Buck up, man up, you can do this.’ And I cannot stand those terms. That’s what the attitude was: ‘It’s all in your head. You don’t have any mental illness, you’re just trying to make us think you’re sick.’ And even though the experts in the field [gave] very good testimony, it was above their heads, the jurors’ heads.”

Many people think it’s just very easy to say, ‘Buck up, man up, you can do this.’ That’s what the attitude was: ‘It’s all in your head. You don’t have any mental illness, you’re just trying to make us think you’re sick’

Mark was convicted and sentenced to life without parole. How did the community feel about schizophrenia after the trial? “Fear, terrifying fear,” Joan says.

In an exception for the prison system as a whole, Mark is responding well to treatment in his facility. “[That’s] all we wanted,” Joan says, “but we didn’t think it should have to be a prison setting.” Mark’s conviction also came of an inadequate defence. Unlike Hinckley, whose parents could afford one of America’s finest defence lawyers, working-class defendants often have to make do with public defenders, a lawyer class facing systemic problems of case overburden and limited resources.

State-provided psychiatrists – guaranteed for poor defendants since a landmark ruling in 1985 – struggle to compete with lucrative private alternatives, too. Resources and availability pose problems. Rural Idaho, the Beckers’ base, has less than one psychiatrist for every 100,000 people. There were inequalities at play in the years before the shooting, too. Mark’s insurance plan had entitled him to psychiatrist sessions lasting just eight minutes a time, and he’d been in a mental hospital quite literally the day before. The family’s attempt to secure a re-trial came to naught, and Mark has resolved against the court process altogether. Getting a hearing to commute his sentence would cost $200,000 in private lawyer’s fees, Joan says: well beyond the budget of most rural Iowans.

Read More:

To Joan Becker, it’s important to remember the success of John Hinckley Jr’s story. Notwithstanding the damage wrought to insanity defences and attitudes around the country, his case marked an acquittal he deserved, a medication regime he needed, and a life now broadly functional. It’s a far cry from the Washington hotel room where he planned to kill.

“I wish they would talk about the success stories that are out there. The people who are overcoming, who learn to live with this illness. Because there are many that do.

“That’s what needs to be reported on: Mark’s hard work of overcoming the voices and working through this disease.” For the American mentally ill of today and times to come, how the picture will change is anyone’s guess. And as long as the insanity defence remains abolished and unfairly constrained, where responsibility starts and ends should frighten us all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments