Cyndi Lauper, lazy socialism, psoriasis and me

In this extract from his book ‘Skin’, Sergio del Molino explains to his son why Cyndi Lauper and her story meant so much to him and how big pharma saved her from psoriasis

There was once, son, a female singer with a shrill voice that made her sound like a ghost child. She composed songs like she couldn’t read or write and danced like she had epilepsy. And yet, she composed, sang and danced in one of the most important songs in the world. Your father, of course, didn’t appreciate the importance of said song until he was very old, as old as you find him now, almost ready for the scrapyard, the age when the things we say might as well not have been said at all, because nobody listens to them.

One has to be very deaf and very confused not to feel the pull of the lyrics of that song, not to dash on to the dancefloor when the melody comes in but, while the world danced and sang along, I sat grumbling at the back of the bar, taking cover behind my 100 per cent cotton t-shirt burka with heavy metal bands on the chest, missing out not only on my own adolescence and ruining the Renaissance of the skin, but showing contempt for a sublime work of art that spoke more directly about my life than all the other songs I’ve ever heard.

At the time – the mid 1990s – the song was already old, though it had never gone out of fashion, given that it had become an instant classic the moment it was released. It was a song for every occasion, just as it is now. It can pop up in the middle of a film, and it’s unusual for it not to get rolled out at any good party. There are more than 20 famous versions of it, and it’s been re-written in every style: ennobled by violins, by melodic singers, set to a jazz tempo, played on acoustic guitars and amid the din of heavy metal, with orchestral touches and even to the accompaniment of church choirs. I like a lot of them, but the original is still the best: ramshackle and rustic, like something played by an organ-grinder.

For the youngster I unfortunately was, frivolity was a crime against youthful humanity, meaning that any chart topper was enough to send shivers of vexation down my spine. Pop was the most banal expression of consumer capitalism and we, the grandchildren of those who lost the Civil War, could not tolerate that bourgeois alienation, that idiotic celebration of ignorance, while the Zapatistas were still having such a hard time of things out in the Lacandon jungle.

The problems of the world were so many and so serious that such gaiety seemed unforgivable. Luckily it wouldn’t be long before Kurt Cobain came along and blasted all the glitter and confetti away, ushering in a time of sad souls in oversized t-shirts, the kind who, even if you couldn’t talk to them because they never actually spoke, you could still see eye to eye with, commiserating with one another over the catastrophic train of events in the world. Some even committed suicide, but most of us made do with deep sighs.

Girls just want to have fun, said the song. And nothing else. The chorus was everything. What? Have fun, for God’s sake? Girls wanted to gaze out of their bedroom windows at the falling rain, or copy out Neruda in their school folders. The girls from my neighbourhood obviously didn’t want to have fun. The clever ones wanted to get good grades so they could go and study medicine. Did my punk ex-girlfriend want to have fun? Was she having fun when she etched Sid Vicious’s name into her forearm with a knife?

If “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” succeeds in transmitting so much truth, it’s because the girl singing it had had such a not-fun time of things. Cynthia Ann Stephanie Lauper was born in Queens in 1953, the daughter of a Sicilian mother and a father who, like Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom, went out for cigarettes and never came back. She lived in a cacophonous immigrant area where everybody was always yelling, and where her musical gifts were quickly noticed. Her family, not insensible to her talent, got her a guitar. She played it endlessly, and that led to a scholarship at an art school at the age of 15. But this wasn’t Salzburg, and it wasn’t operas she was composing, and the frantic pace of things in Queens meant she took her eye of the ball. She couldn’t keep to the Calvinist rhythms of the institution.

It was the end of the hippy era and almost more unusual for young people not to run away from home. Cyndi became a drifter, playing in bars with sawdust floors and taking waitressing jobs in whichever towns she wound up in. She was a good singer, and stole the hearts of all those roughneck audiences, and had soon joined a group and secured a small record contract. Everything seemed to be heading in the right direction but in 1977, when she was 24, she developed a vocal-cord disorder and, hugely distressingly, lost her voice.

Goodbye, the stage. Goodbye, record contracts. Goodbye, money.

Cyndi went back to the life she hadn’t by any means managed to get away from. To asking if they needed staff in the bars and shops, to scraping together that month’s rent, and to never having any fun, because having fun was expensive.

When she got her voice back, she teamed up with a couple of musicians and happened upon the thing every artist happens upon when they’re least looking for it: a manager. A guy who saw them play offered to cover their costs and find them gigs and a record deal. They decided to call themselves Blue Angel, and the record they made was a critical success. Which is to say, the critics who got sent free review copies were impressed, but no punter paid a dollar for it. The copies in the shop windows went untouched, and were sent back to the record warehouse in the same boxes in which they had arrived. The manager, just as willing and affable as ever, left them hanging, at the same time demanding they pay back huge sums which Cyndi simply didn’t have.

Back to square one. Back to asking around in Soho, did anyone need a store assistant or a waitress or a till girl. Any job is fine, I need the money.

Cyndi was pushing 30, and too many opportunities had passed her by. She wasn’t the lovely looking young thing any more that the Italian storekeepers of New York took pity on, but a grown-up, one without any particular skills to offer, and she was starting to become a nuisance. As if losing her voice hadn’t been enough, it had left her singing voice altered. In the view of certain critics, and in her own eyes, it was more expressive now. In the view of the drunken roughnecks in the bars where she sang, she sounded rattier, and much less sexy.

What it should have said was: when the working day is done, the girls just want to appropriate the means of production via a violent uprising led by a revolutionary vanguard that will crush all capitalists and install a dictatorship of the proletariat

According to the theory of fairytales, this is a very late point for the arrival of the knight on his white horse. The princess is beyond saving, and her lot ought now to be the same as the Moorish princesses shut up at the very top of the highest towers: languishing until death, enumerating her wrinkles, or bringing things to a swift conclusion by throwing herself off the parapet.

But, beyond the realm of fairytales, the knight shows up when he feels like it, and David Wolff was apprised of Cyndi Lauper’s existence on a night out in New York when, having settled in for the night at a certain bar, he watched her extract a few lazy, uplifting chords out of the guitar. It’s no exaggeration to say that he fell in love there and then. He offered her everything a producer can offer a girl with a guitar in a New York club in the wee hours of the morning, and Cyndi, who’d had enough of producers offering her palaces and gardens, passed on the offer of drinks and went home to bed, in anticipation of her double shift in the morning at the supermarket or café or wherever she happened to be working at the time.

But Wolff was a hero in the true tradition of chivalry, of the kind who burst into record company offices and refuse to go away until they get some cynical, coke-snorting executive to listen, from beginning to end – Don’t go anywhere! There’s more! – to the whole rough-cut of the girl who’s going to be your new star. Guaranteed.

If you say so, they replied, half-heartedly holding out a cheque, because they knew that the only way to get rid of him was to give him a cheque.

It was a contract with one of the subsidiaries of a big label; in other words, the company, not completely sold, was proceeding cautiously. It wasn’t a bad contract, but it wasn’t great either. Good enough, from Cyndi’s point of view. She’d record an album, she’d work hard to make a success of it. With luck, she’d earn a bit of money and pay off her debts. No, not bad.

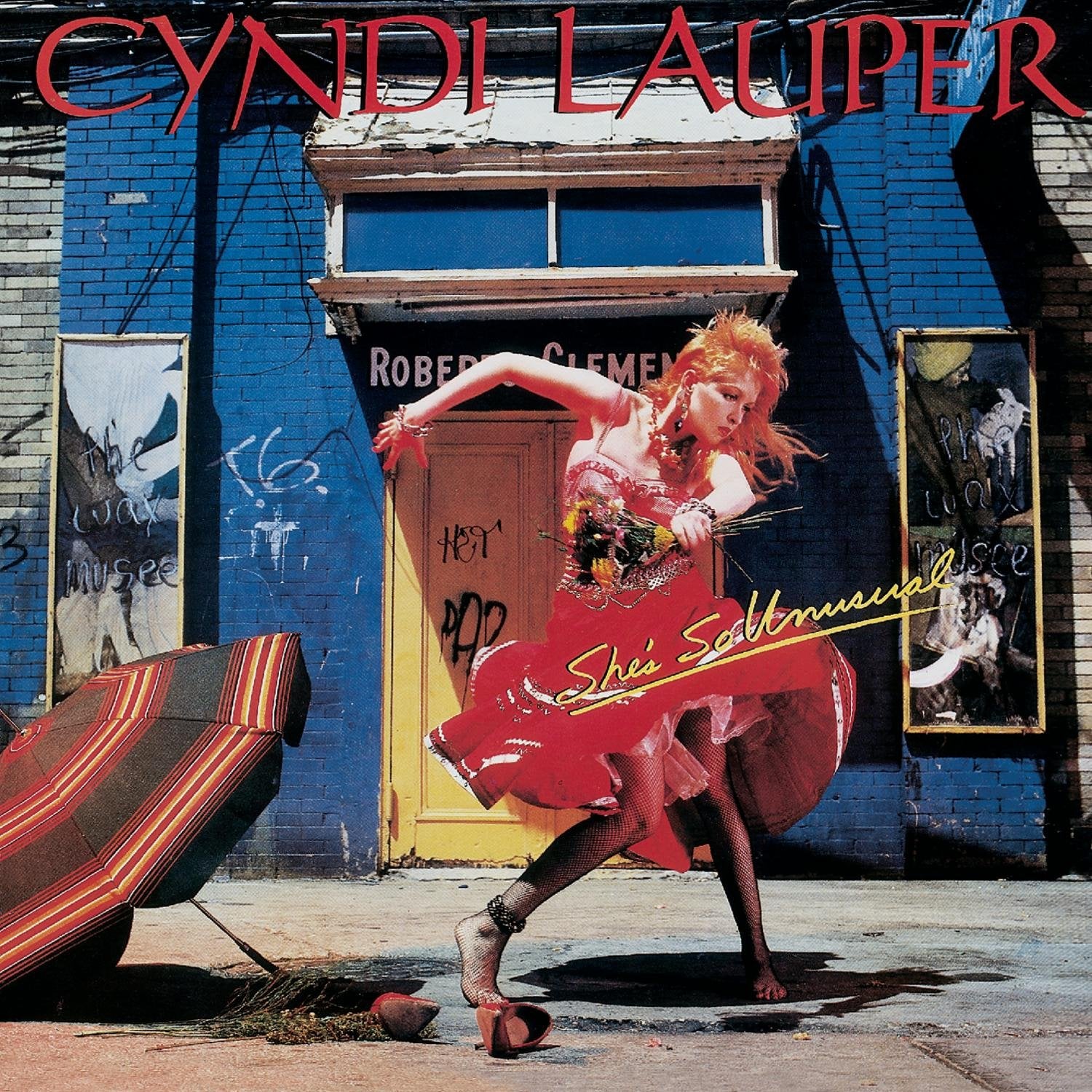

She’s So Unusual came out in September 1983, and “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”, which was the first single, went into heavy rotation on all the radio stations. MTV picked up on the music video, which was practically a home video, the cast made up of Cyndi’s mother, a famous boxer from Queens who took a shine to Cyndi and agreed to play the boorish Italian father, and all her friends and collaborators who, in exchange for a few beers, proceeded to dance around and make up the numbers in the least self-controlled, least professional way imaginable.

The craziness had begun. The song became an anthem within a matter of weeks. No sooner had the LPs been pressed than they would fly out of the stores. It went to number one in more than 10 countries, and number two in the US. And Cyndi Lauper became a legend.

“Girls Just Want to Have Fun” wasn’t her own song. One of the label’s regular songwriters, a man, had come up with it, but Cyndi rewrote it completely, all except for the chorus. The original had been about a womaniser whose huge number of conquests was down to the fact (it apologetically explained) that girls just want to have fun. In Lauper’s hands, this macho nonsense was transformed into a piece of working-class feminist affirmation. “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” is the greatest socialist song ever written.

My adolescent self didn’t think a socialist song should say, as this one did, that “when the working day is done/ girls they want to have fun”. What it should have said was: when the working day is done, the girls just want to appropriate the means of production via a violent uprising led by a revolutionary vanguard that will crush all capitalists and install a dictatorship of the proletariat. But even my adolescent self understood that it was difficult to turn Marxist adages into something that both rhymed and would get people singing and dancing along.

The same thing happens with Marxism as happens with religions: any literal reading of the sacred texts destroys the poetry contained. Marx’s son-in-law, Paul Lafargue, became the first heretic to read his father-in-law in his own distinctive way, going on to write a short, ill-fated opuscule called The Right To Be Lazy. That Lafargue was a Cuban mulatto with French blood has been the inspiration for a multitude of jokes. Who else but someone from the Caribbean could have been the first Marxist to defend the right to put one’s feet up? The German founding fathers were labourers who did piecework, and they believed their movement was all about working more, not less. Socialism didn’t build itself, and it didn’t come about letting idlers into the movement either. Revolutions are always for those who put their shoulders to the wheel.

Socialist orthodoxy promotes a useful kind of leisure, one that is oriented towards the complete realisation of one’s personality, something only possible in a world where class has been done away with. The dream of any good socialist is a society comprising disciplined workers who take responsibility for their actions, and who read Shakespeare and listen to Bach in their free time, thereby neatly appropriating bourgeois culture as well. Things were to be seized in the following order: first the factory must be appropriated; next the palaces and all the furniture they contained; and finally, culture itself. But nobody here is talking about having fun; it’s about sacrifices. It is a serious process involving men with beards.

This is the socialist idea that ended up with Stalin’s splashing about in his Sochi swimming pool. So utterly focused were they on the revolutionary task that they failed to notice that the person who steals from and murders a tyrant in order to occupy his place and move into his palace, will perforce end up becoming that same tyrant. Or something worse: a tyrant who believes he is in the right. The Greeks knew this very well: the sure-fire way to turn into your father is by murdering him.

The socialism of laziness, or Lauperian socialism, begins by washing one’s hands of power. Power brings out the despot in everyone. Not just that, but the simple desire for it reveals an authoritarian bent

The socialism of laziness, or Lauperian socialism, begins by washing one’s hands of power. What do I care who’s in charge, if those in charge always do things the same way? Power brings out the despot in everyone. Not just that, but the fact of wanting to exercise power, the simple desire for it, in itself reveals an authoritarian bent with which it’s better simply not to have any dealings.

Lauperian socialism resigns itself – with an elegance that Nietzsche would have applauded – to the fact that power is always going to be your undoing. Even if your best friend is the one in charge, it makes no difference. Power, in and of itself, is shit, and it comes raining down on any who submit to it. The starting point, therefore, is to recognise the way it functions among us. If socialism’s subject is people being screwed over, we should look to ourselves, the screwed over of the world, and come up with our own reading of the final stirring speech in The Communist Manifesto, the one concerning the proletariat having nothing to lose but its chains, and a world to win.

The bearded, frowning, industrious socialists believed the world they were playing for was that of political power. Hence why they sought to get their names on the ballot, in the places where ballot boxes existed, while others dedicated themselves to massacring the Tsar’s family, in the places where tsars with families existed. But Lauperian socialism isn’t gunning for the banal, foul-smelling world of politics. Winning the world doesn’t mean ruling over it, but living in it however the hell you choose. We Lauperian socialists want the world so that we can dance around and go for nice strolls in it, and enjoy it without having to explain ourselves or ask anyone else to explain themselves.

This, technically, wouldn’t be a socialist line of thought, but an anarchist one. Yet it enters indubitably socialist territory when the chorus says “When the working day is done”; a clear expression of the Lauperian socialist’s firm commitment to work. Having recognised that those being screwed over are, fundamentally, the people that go out to work, they don’t renounce work, which serves as a means of solidarity and social cohesion. The doctrine was born in Queens, among the offspring of Italian immigrants: work is the only thing that defines them. Okay, the idea goes, we’ll keep up our end. We’re workers, and we go out and earn a buck, but when the working day is done, we are ours and ours alone, we belong to us. And we make our own fun.

Being expressed in feminine terms, the doctrine is more resounding still, because even the most obtuse male socialists allow themselves a certain amount of fun, and some of the laziness of workers. On the way home from the factory, they could stop by the working men’s club (given that the pub is a place of pure alienation, and the cinema all about capitalist propaganda), but that didn’t go for the female of the species, with the children’s dinner to cook and the washing to do. Since the times of the Vestal Virgins, women have been the instrument of male fun, but not allowed to have fun themselves.

Since the times of the Vestal Virgins, women have been the instrument of male fun, but not allowed to have fun themselves

In the Galician village where we spend our summers, there’s still a washroom with a stone basin fed by the river on the banks of which the village stands. The council has put up some museum posters there, explaining the history of the place by way of a homage to the local women, for whom it was a social space, somewhere to have a chat and a laugh.

What a miserable thought. Those texts were saying that generation upon generation of women had lived as slaves in their own domestic situations, and the only time they were able to interact with people from outside their families, and to form friendships, was when pounding clothes against the wash stone on sunny winter mornings until the skin on their hands became cracked and dry. There, free of the surveillance of their husbands or the local vicar, they could express themselves openly, share intimacies, tell jokes and laugh and laugh until they were in stitches. Those girls had fun, yes, but a hysterical, hopeless kind of fun, very similar to that of prisoners allowed out for a couple of laps around the prison yard.

The revolutionary key to the hymn is contained in the line: “I wanna be the one who walks in the sun.” Fun is something social, it can’t be experienced in a washroom on the outskirts of the village, hidden from the censorious male gaze. The fun I have is not a private act of faith that you can simply ignore. My laughter has to rise all the way to your window. You aren’t going to be able to pretend I don’t exist any more. I’m here, I’m in the world, and if we cross paths, you’re going to see me in party mode. And maybe I’ll wake you up when you’re sleeping. And maybe I’ll offend you when you’re coming out of church with your family. And maybe I’ll make you feel uncomfortable, and ruin your well-mannered silence as you promenade around the public gardens. And if that happens, deal with it, because girls just want to have fun – you can take yourself off to the public washroom, I’m going to run through the city centre in my dirty clothes.

Her psoriasis covered almost her entire body in enormous plaques, leaving her quite deformed, more akin to a swamp monster or zombie with the flesh falling away in sheets

Cyndi Lauper puts herself out there as a girl who wants to have fun, and as an artist on a stage or the silver screen. Her body is just as expressive as her voice, and her fragile, child-like, almost porcelain appearance contrasts greatly with her spasmodic dancing and the feline way in which she swipes at the air. When she bursts on stage, or goes out in the street, you simply can’t look away. Her magnetism is such that she seduces record producers when they see her in a New York club in the wee hours of the morning. “I wanna be the one who walks in the sun” is a radical declaration of intent: she will never hide, never cover herself up, never make an enigma of herself. In Cyndi Lauper’s skin, the whole light of the world is reflected.

Which was why it was so tragic when a dermatologist one day confirmed the diagnosis she had been fearing: Miss Lauper, you have a very serious form of psoriasis.

The party girl who, in times past, would have been condemned as a witch, condemned to the kind of affliction suffered by witches.

The diagnosis came late on, in 2010, with pop iconicity long since having watered down her personality, and her body, her pale skin and her almond-shaped eyes become museum pieces and registered company brands. A really awful psoriasis that covered almost her entire body in enormous plaques, leaving her quite deformed, more akin to a swamp monster or zombie with the flesh falling away in sheets.

The outbreaks were very aggressive. In her own words, she felt like she was being boiled alive. She spent days in bed taking painkillers and antipyretics, because she kept having sudden fevers; her skin had ceased to be able to regulate her body temperature. The evil had taken its anger out on her in the worst way possible.

Anyone in her position would have sought refuge in smoke and mirrors. Lauper, who by this time was writing and producing Broadway hits – with some success, she had just won a Tony Award for Kinky Boots – could have gone and hidden backstage, turning herself into a masked shadow, but such a retreat would have been a betrayal of her very own war cry: “I wanna be the one who walks in the sun.” With her scaly skin – that fun-loving girl strutting her red-dressed stuff in the streets of a summery New York ancient history by now – she decided to stick to the guns of her Lauperian socialist doctrine. The world was going to find out all about her illness in the same way it had found out about her fun-loving urges.

Lauper has spoken in detail about what she calls – with no Hitlerian puns intended – her struggle. She has even released photos of parts of her body completely covered in erythemic lesions, more the kind of thing one would expect in a dermatology manual than a pop-music magazine. She wants to tell a story with a happy ending, and thereby help other people who are ill. This isn’t uncommon among the handful of famous women who have admitted to suffering from psoriasis: they put themselves on show as a way of normalising their travails.

For example, the Olympic swimmer Dara Torres, who by virtue of her profession has to be out there in a swimming costume. Or the model Cara Delevigne, who fills her social media channels with hang up-free, in-your-face photos of the blotches and plaques all over her body, her attitude like that of a gangster rapper, defying anybody bold enough to leave a comment. Or the unclassifiable postmodern star Kim Kardashian, who abstains from putting make-up on her lesions, or covering them in any other way, and talks about them with complete and unflinching openness.

As a general rule, famous women with psoriasis show more, and confess less than males of the species. They are moved, furthermore, by a didactic wish for solidarity that goes beyond self-esteem and chutzpah. The few women bold enough to make a show of their illness do it intending to help the thousands of sufferers whose experience is one of shame and angst.

They put it in perspective, they laugh at themselves, they give practical advice for overcoming the day-to-day difficulties, and take a leading role in associations for sufferers and dermatological institutions. Male psoriasis sufferers, on the other hand, don’t pose for the cameras, we hide our skin under shirts and jackets, and when we talk or write about our illness, do so in self-absorbed, tragical tones, without the slightest interest in helping others or putting ourselves forward as an example.

Psoriasis is our crown of thorns, and the story we have to tell is of a suffering passion, but with no moral to it, no promise of redemption, either for our own sins or those of humanity. Some powerful men may even seek to use it as an attribute of power, which is what we get a sense of from the Stalin tarot card.

It may be that this isn’t down to a difference of attitude between men and women, but rather that the best testimonies we have about the illness were written by intellectual males, and the women sufferers we know about are public figures, but not literary or political types. Perhaps what we are missing is a Simone de Beauvoir or a Virginia Woolf with psoriasis, capable of sublimating the experience of the skin through an intellectual feminist, feminine filter.

From the time of Cyndi Lauper’s diagnosis, she has felt the need to become a kind of Blessed Virgin, someone for the lepers and plague-sufferers of the world to come and present their votive offerings to. Saint Cyndi shows in her words how close socialism (even the Lauperian kind) is to religion, and how easily it can turn into it.

She put herself at the disposal of dermatological institutions and of patient collectives, talking widely about her experience and offering people advice. She places great emphasis on the avoidance of stress, something that she, naturally very highly strung, only managed through studying and practising reiki. Be careful what you eat, avoid fatty foods, chocolate and alcohol – these were also important.

What else? Well, dedicating time to yourself. Putting aside five minutes every day that nothing and nobody can violate. Have a space, a room to yourself. Yoga when you wake up in the morning. And meditate, meditate a lot. She followed a Tibetan guru, Pema Chödrön, whose voice took her to nirvana, or somewhere near to it, but she also recommended, as something more achievable for the public at large, a meditation app created by Russell Simmons . . .

And be good, of course . . . And smile, and love your family, and let yourself be loved . . .

Oh, come on, Cyndi! What guff.

Anyone suffering from psoriasis knows there’s no way to meditate when your skin is screaming at you to scratch it, and nothing changes if you cut a few ounces of chocolate out of your diet, or dunk a piece of bread in your stew, or take down a bottle of wine with supper.

What works are drugs. The hard ones, the expensive ones. The ones made by big companies who don’t have Tibetan gurus. And Cindy knows it. Of course she knows it.

In 2018, the pop star Cyndi Lauper put out her latest song, entitled “Hope”. Lightyears away from the majority of her hits, it’s a ditty offering high-fives of encouragement inspired by her struggle with psoriasis. It stays true to the core Lauperian socialist philosophy: look at me, it says, look at us. It is coherent with her insistence on bringing life’s bit-part actors and extras to centre stage. But, beyond that, “Hope” is a hideous piece of affectation unworthy of the freshness and fun of Lauper’s best work. It urges us to look at those whom society leaves hidden, or who hide themselves away out of fear of that society. It urges us to look at the monsters, but in the music video, those monsters are all scrupulously covered up. And that includes Cyndi herself, who at 65 years of age maybe doesn’t feel all that much like running along the streets of Queens in summer dresses any more.

Cryptic and banal, but a flat sort of banality, not like the militant, polymorphous banality of years gone by. “Hope” could only be uplifting to the simplest souls in the purgatory of plague victims.

I have no issue with Lauperian socialism, which was founded in order to vindicate working-class girls having fun, ending up as a tool of international capitalism. The disagreeable bit is that it should hide behind Reiki and meditation

But the important thing about “Hope” is neither the song, the music nor the lyrics. The important part is that it wasn’t produced by any label, or anybody in the music business. It was mixed and promoted by Novartis, one of the biggest pharmaceutical firms in the world and the company that markets Cosentyx, which is among the most effective psoriasis drugs available.

Cyndi Lauper can disseminate all the hope she likes with desultory verses, and give any amount of advice to meditate and regulate one’s breathing, but what has really saved her have been Cosentyx shots, a medication of great biological complexity developed in the most cutting-edge, jealously guarded laboratories in the world.

Novartis has spent many years focusing on treating the root causes of psoriasis. That is, they don’t look to treat the symptoms, as was once the case with the creams and corticoids on the market – and as is still the approach for less serious cases – but by de-activating the biological mechanisms that provoke them. Since they discovered that psoriasis is the cutaneous expression of a group of far deeper autoimmune illnesses, the research has focused on how to alter the patient’s immunological system so that it stops attacking itself. Because suppressing the body’s defences is easy, as any cancer sufferer knows: this, basically, is what chemotherapy does. The key is to do it in a way that is at once efficient (that is, which whitens the skin and eliminates the rest of the symptoms, like arthritis and rheumatic issues) and safe (that is, that doesn’t leave the patient shorn of an immune defence system, condemned to live their life in an aseptic bubble in order to avoid dying any time they catch cold).

I have no issue with Lauperian socialism, which was founded in order to vindicate working-class girls having fun, ending up as a tool of international capitalism. The disagreeable bit is that it should hide behind Reiki and meditation, and not be bold enough to speak its true name.

The Cyndi Lauper of 1983 who wanted to walk in the sun would have come out in favour of Cosentyx shots, and would have sung: when the working day is done, girls just want to cure their psoriasis through scientifically proven methods. Girls don’t want to waste their time with Tibetan mantras or drink chia water instead of coffee.

The Cyndi Lauper of 1983 would finally get together with her manager, her Sicilian mother and her loud-mouthed Queens cohort and, dancing with robotic jerks and spasms and a fluttering red dress, storm the Novartis factory and hand out Cosentyx shots among all her admirers who were suffering from psoriasis. She herself would do the injections with disposable syringes, while singing over and over that girls just want to have fun. The Cyndi Lauper of 1983 would get the Tibetan guru Pema Chödrön into a conga while transforming his sacred hymns into jokes.

Cyndi Lauper and I appear condemned never to meet on the same side of life. My adolescent self, so disdainful of her desire to have fun, and unable to understand the greatness of her socialism, would have taken Pema Chödrön’s meditation techniques and her current-day para-scientific advice very seriously, while decrying the instrumentalisation of her message by the Big Bad Pharma industry, and I’d have thrown in some adage by Subcomandante Marcos for good measure. Whereas my current day self, who admires and hold his hands up to the Lauperian socialism of the girls who want to have fun, can’t stand the orientalist mysticism of “Hope”. My younger self aligns with her older self, and her younger self aligns with my older self.

Something as big as “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”, the cultural weight of which was far superior to the majority of the artists and writers lauded in every culture section of every national newspaper, doesn’t lose all its lustre just because of a self-help ballad paid for by Novartis all these years later. The good thing about masterpieces that come early in an artist’s career is that they redeem all the subsequent self-indulgence: a spark of youthful brilliance inoculates against a disoriented old age.

The mange-ridden, the monsters, the witches, the lepers and all of those drifting downstream in the Ship of Fools, pulling up at the lazarettos on the banks, won’t find the slightest inkling of hope in “Hope” but we can have a good old dance to “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”, while those in their right minds, and those with their good looks, the athletes and the elegant folk, laugh at us from the shore.

We can go on proclaiming our right to walk in the fresh air and have a good time. Lauperian socialism vibrates in every one of the 20-plus versions of a song that rebukes us for feeling so sorry for ourselves. Don’t scratch yourself, show yourself. Look at others, and let them look at you. I would have liked to understand it in the years I wore black t-shirts and didn’t go walking in the sun, when I hid away at the backs of bars, but I wasn’t yet the monster then that I’ve now become.

Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead

To get a copy of the book click here Skin (politybooks.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments