Coronavirus and America’s urgent need for universal healthcare

The pandemic suggests that Darwin’s theory of survival of the fittest will no longer hold true; it will become survival of the richest. The virus is now one of the strongest arguments for Medicare for All, says Ahmed Twaij

With the rapid global spread of coronavirus causing more than 170,000 infections as well as the collapse of economies around the world, its effective containment is becoming more important. President Donald Trump’s plan for the management of the disease, officially named Covid-19, is typical of a for-profit private healthcare system. The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the reasons why universal healthcare coverage is vital, and the disease has become one of the strongest arguments for Medicare for All.

Fears linked to coronavirus – or “caronvirus”, as an ill-prepared Trump called it – have caused New York’s S&P 500 and London’s FTSE 100 to record their biggest daily losses since 1987’s Black Monday. The collapsing US economy, which the president had previously incorrectly boasted as being “the best it has ever been”, forced Trump to announce a plan to tackle the virus, nearly two months after the World Health Organisation declared it a global emergency.

“Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”, the fundamental rights penned by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, are seven crucial words held dear by all Americans. These inalienable rights, however, are denied to millions of Americans who do not have access to basic healthcare, and with growing concerns over coronavirus, these principles are even more at risk.

The US healthcare industry is founded on the notion of free-market capitalism, assuming that competition between healthcare providers autoregulates the industry to deliver the best, most affordable service. Given that health has been defined as a basic human right, the spread of coronavirus has revealed the cracks in this private health economy. In essence, private healthcare providers can charge patients any price they want, leaving those most vulnerable at risk of remaining untreated and simultaneously facilitating the spread of infection.

The virus, much like the common cold, is an airborne pathogen. Anyone can catch it, from the young and fit to the rich and powerful. Even a British health minister, Nadine Dorries, has tested positive for the disease. A sneeze, cough or simply being in the vicinity of someone with the infection is all that’s needed for transmission, which has rapidly transformed the disease into a public health emergency.

The US’s private healthcare system means that treatment for the virus will only be available to Americans who can afford it. As the rate of uninsured Americans continues to increase year on year, those unable to access coronavirus diagnosis and treatment also increases. Without universal healthcare, effectively managing the spread of coronavirus or a more lethal epidemic will be impossible.

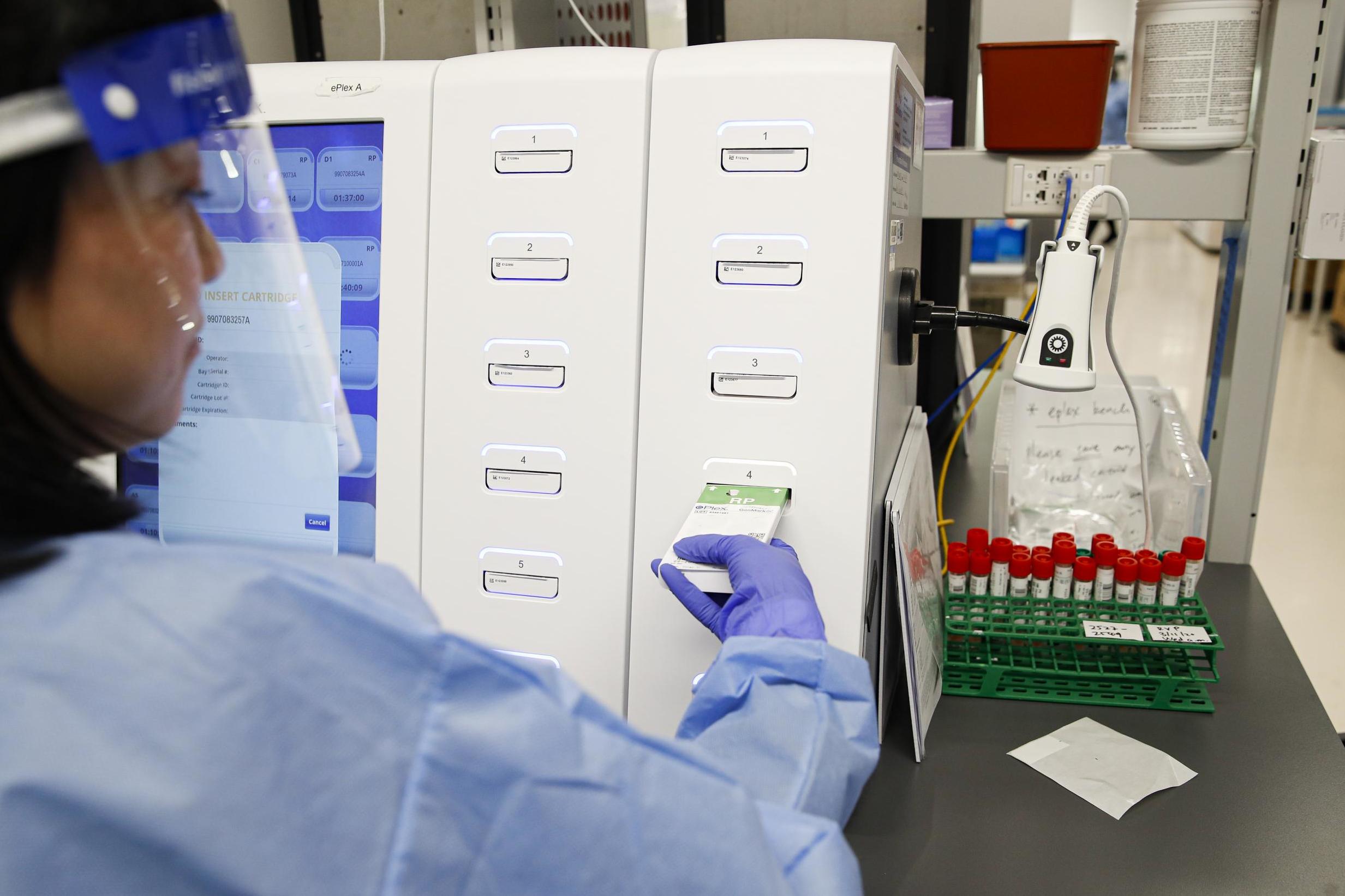

Across the US, it’s been found that 44 per cent of Americans have skipped doctor visits because of the cost. Often, many leave visiting a doctor too late for any treatment to be beneficial. In one case, a Florida man’s concern that he had caught coronavirus racked him up a bill of $3,270 for merely obtaining a blood test and nasal swab, as well as doing the right thing for protecting public health.

It can be expected that many more Americans will follow in the president’s stead and avoid seeing their doctor, brushing off symptoms and potentially igniting an epidemic

So far, though more than 4,000 individuals have been diagnosed with coronavirus in the US, the chances that you will catch the disease in a country of over 300 million remain low. But the number of uninsured Americans reached nearly 30 million last year. To save $3,270, many will probably hedge their bets on just having the flu and avoid seeing a healthcare provider. The ensuing lack of quarantine will make containing the disease impossible, and the crisis in Italy will likely be replicated across the globe.

Trump, setting a dangerous precedent, initially refused to get tested for the virus after potentially being exposed. Downplaying the disease, he claimed: “I don’t think it’s a big deal, I would do it but I don’t feel any reason – I feel extremely good.” Worryingly, he failed to understand that it takes up to 14 days for individuals to show any symptoms, while they still remain contagious. It wasn’t until Friday that he deigned to be checked out, the negative test result being announced the following day by Sean Conley, the White House physician.

It can be expected that many more Americans will follow in the president’s stead and avoid seeing their doctor, brushing off symptoms and potentially igniting an epidemic by spreading the virus, oblivious of their risk to the public. As the disease spreads, millions will be left unable to afford treatment. Darwin’s theory of survival of the fittest will no longer hold true; it will become survival of the richest. Were a form of universal healthcare to exist, such as Medicare for All, these concerns would never exist, and containing the disease would be possible, with people willing to seek professional healthcare advice.

The US economic system celebrates individualism through a free-market economy, a system that has paved the way for the wealthiest three Americans to amass more wealth than the bottom 50 per cent. This political ideology snowballed throughout Ronald Reagan’s presidency, who, in his inaugural speech as president, famously announced: “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.”

What Reagan implied is that government-imposed regulations slow the nation’s economic growth. What he didn’t comment on is the impact of deregulation on the living standards of the average US citizen. Sure enough, under Trump, the US economy has grown through his pro-corporate policies. However, the US has witnessed an increase of seven million adults without health insurance.

Reagan’s economic ideology, shared by the then British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, paved the way for widespread neoliberal reforms, mass privatisation and market deregulation. Healthcare was included in these sweeping changes. Hospitals began to be run as for-profit businesses, with caregivers now no longer accountable to their patients, but to directors, shareholders and the bottom line.

The Reagan-era zeitgeist allowed for healthcare spending to soar, but without reflected gains in life expectancy. No longer were patients seen principally from a human rights perspective – it became the age-old story of supply and demand, with patients seen as customers and profit maximisation as the priority. This form of individualism allows for the American Dream to prosper: that is, if you work hard, you too can become a billionaire, even if at the expense of the health of others. For this reason, many in America who can afford private healthcare are impervious to the needs of those who cannot, and continue to want their individual choice of healthcare access.

When assessed through an economic lens, if a patient gets an individual-specific, non-contagious disease like cancer and cannot afford the treatment, then it is not so bad: only the patient and their loved ones suffer – a devastating thought, but a manageable concern. The cost of cancer treatment in the US can reach up to $100,000 per month, and 63 per cent of cancer patients report financial struggles following their diagnosis. If a cancer patient delays seeing a doctor for fear of the costs involved, the worsening of the disease only impacts their own life expectancy. With broader American society fearing all aspects of socialism, including universal healthcare, such deaths due to lack of funds are often brushed over.

Over 20 pharmaceutical companies are already in a ‘race’ to discover an effective vaccine, a product projected to make $20bn in stock market value

But the highly contagious coronavirus has become a global pandemic, and the more people infected, the wider it will spread. It has already left whole regions of Italy under quarantine. Across Europe, football games, normally played in front of tens of thousands of fans, were held behind closed doors before being called of altogether. In the US, Democratic presidential candidates have cancelled campaign rallies due to coronavirus fears (while Trump continues to announce more events).

Unlike with cancer, if patients catch coronavirus and cannot afford to see a doctor, and so choose to ignore their symptoms or leave the treatment too late, not only will they suffer – all those who have been in contact with the patient, rich or poor, will be at risk too. The fallacy of individual choice in healthcare cracks when diseases are of public concern.

To effectively combat the virus, preventative measures are being planned across the US, including the development of a vaccine. The prospect of a new vaccine being needed by all Americans will likely have the pharmaceutical industry salivating from the potential earnings. Over 20 pharmaceutical companies are already in a “race” to discover an effective vaccine, a product projected to make $20bn in stock market value. Two companies, Gilead and Moderna, witnessed their stock prices rocket by 10 per cent and 31 per cent respectively as they announced their vaccines entering phase I (Moderna) and phase III (Gilead) trials.

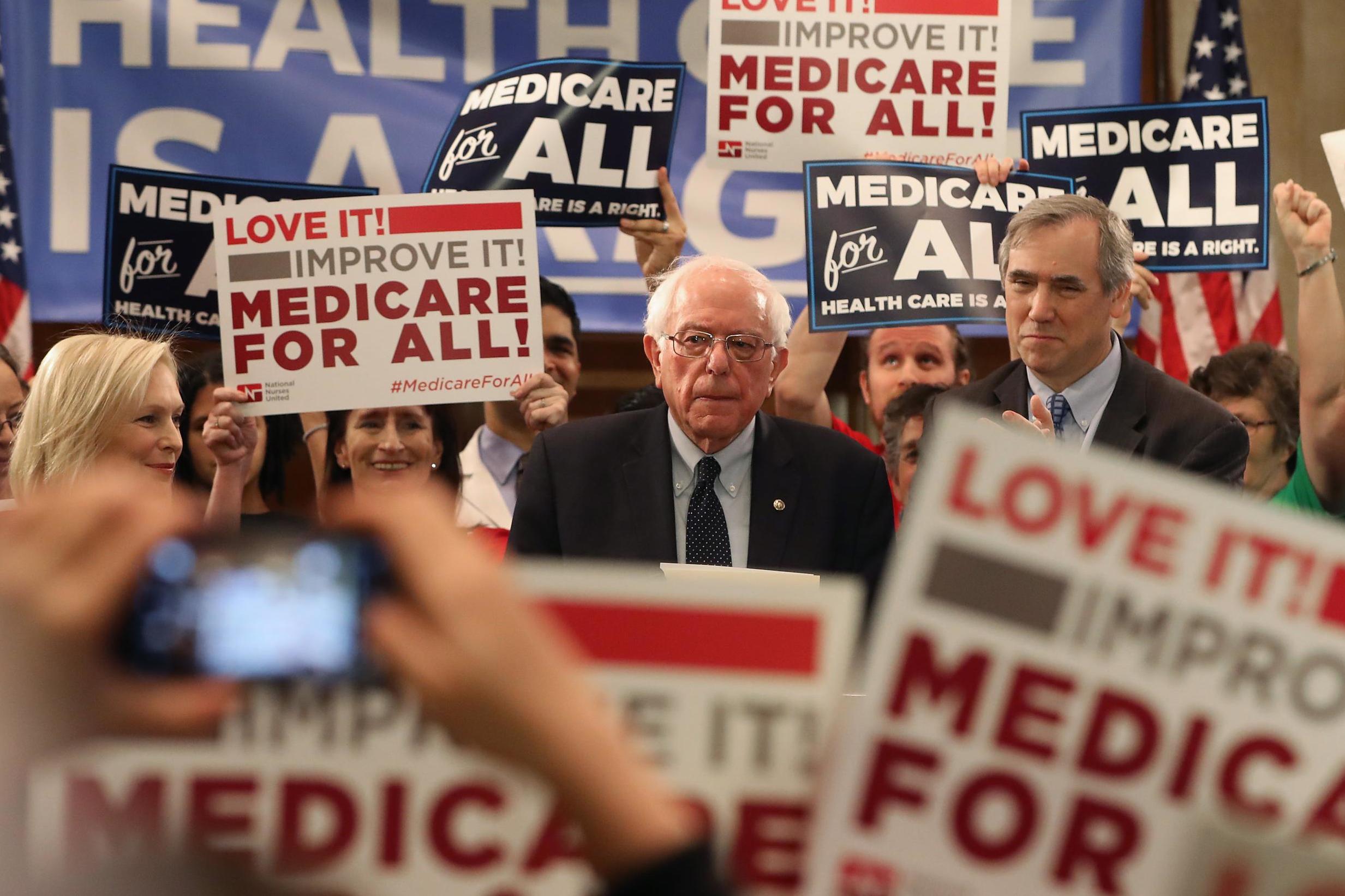

US health secretary Alex Azar has declined to promise that a coronavirus vaccine will be affordable to all Americans, stating: “We need the private sector to invest … price controls won’t get us there.” Leading Democrat Nancy Pelosi has also refused to demand a free vaccine. Senator Bernie Sanders is the only presidential candidate calling for the vaccine to be free, and has faced criticism for doing so.

The US healthcare industry has long been held hostage by Big Pharma’s pricing of life-saving medications, which has sent millions of Americans into bankruptcy for seeking treatment. It’s even left some Americans trying to “go viral or die trying”, using crowdfunding schemes to fund expensive, potentially life-saving treatments. This is down to the unregulated healthcare sector allowing pharmaceutical companies to dictate prices. NerdWallet has estimated that medical bills resulted in 57.1 per cent of all US personal bankruptcies, despite many people being covered by insurance. Private insurers can be unreliable, and charge high prices for premiums that leave many costs uncovered – so much so that a secondary, supplemental health insurance industry exists to cover these remaining costs.

Patients with life-threatening conditions can be left to choose between paying the extortionate prices set by a pharmaceutical company or death. If a company like Apple decides to exponentially increase the cost of the iPhone, it will notice a reduction in sales. But with medications, disease sufferers have no other option. In 2015, Martin Shkreli, aka the “Pharma Bro”, acquired a life-saving antiparasitic drug, Daraprim, and immediately hiked up the price from $13.50 per pill to $750. With patent laws meaning no other options for treatment were available, the 5,000 per cent overnight price increase left many facing either financial ruin or death.

The Daraprim example is not an isolated incident. Lomustine, a vital cancer medication, saw its cost increase 15-fold in 2017. Shockingly, cycloserine, a medication used for dangerous multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, had its price increased from $500 for 30 pills to $10,800 after being acquired by Rodelis Therapeutics. Unjustifiable exploitation of the vulnerable reflects the moral bankruptcy of an unregulated healthcare system.

Under pressures from the pharmaceutical industry and its own targets, the FDA has at times rushed through ineffective drugs or those with potentially adverse effects

The widespread need for a coronavirus vaccine could be vulnerable to similar profiteering, considering this administration’s refusal to ensure regulation of the vaccine. And without a mass uptake of vaccination, the disease will continue to threaten lives across the globe. If we are serious about Covid-19 prevention, not only should the government regulate the cost of the vaccine, it should also provide funds to enable free access for all.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for approving which medicines make it to market. Under pressure from the pharmaceutical industry as well as its own targets, the FDA has at times rushed through ineffective drugs or those with potentially adverse effects. Hurried approvals have been noted to have double adverse effects. Tamiflu, seen as the almighty saviour to 2009’s swine flu pandemic, was swiftly approved by the FDA “under the pressure of providing pharmaceutical solution to a pandemic disease”, wrote Yogendra Gupta, a professor of clinical pharmacology.

Tamiflu was later found to have no effect on reducing dangerous complications nor on preventing the spread of the flu. This discovery was too late, considering the US had already spent $1.3bn and the UK £424m on the ineffective drug. With the potential of a coronavirus vaccine being teased to the public, a focus on efficacy is vital, and the pressures of profit margins should not dictate the race to approval.

Profiteering in healthcare has not always been so common. The patent for insulin, for example, was sold for $1 in 1923 as the discoverers, Frederick Banting, James Collip and Charles Best, refused to put their name on the patent. Feeling it unethical for doctors to profit from discoveries that would save lives, Banting wanted all those who needed the treatment to be able to afford it.

Given that thousands donate to charities such as Cancer Research UK, and that almost 17 per cent of all drugs approved in the EU originated from not-for-profit organisations, it is immoral that the prices of drugs are hiked up once they’ve been acquired by the pharma industry. Bill and Melinda Gates have pledged to donate $60m through their foundation to research a coronavirus vaccine. If the market value of the vaccine, once discovered, prices out many from receiving it, then such donations are enabling exploitative policies by Big Pharma, and the money may be better spent on ensuring universal access to healthcare.

A common argument against universal healthcare is the cost. Throughout the Democratic primaries, the cost of a Medicare for All bill has been estimated at around $32 trillion for its first decade. To be clear, that’s $3.2 trillion per year – such figures have instantly been made available to prop up the collapsing US stock market in the past. The US Federal Reserve dramatically injected money into the market amid the coronavirus meltdown, most recently pumping in $1.5 trillion overnight. As Sanders reminds us: “Every other major country has made healthcare a right for all. Anyone who says the United States cannot do the same is selling the American people short.”

It was not until the rise of the Cold War that such socially beneficial policies were scolded for being too communist

Part of the problem here is that the unregulated healthcare market has allowed for soaring costs – of all OECD countries, the US already spends the highest percentage of GDP on healthcare, paying nearly 17 per cent in 2018. This magnifies any potential burden of Medicare for All on the taxpayer, making it less appealing. For instance, the cost of an infusion of saline, a likely baseline treatment for coronavirus infection, can reach hundreds of dollars, when the manufacturing price is as low as 44 cents.

In contrast, in the UK the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme and the NHS National Tariff help set guidelines to keep drug and treatment prices to a minimum. As an example, the cost to the NHS of a CT scan of the lungs, a likely investigation needed for treating coronavirus patients, is £100, whereas in the US, the national average for a CT scan is over $3,000. Such price regulation has helped the NHS continue providing care for free to its patients, and it has now expanded its free coronavirus testing to all patients, regardless of residency. Although other factors also play a role, the current mortality rate from coronavirus infection in the UK, with its universal healthcare coverage, is at just over 1 per cent, compared with the US at over 3 per cent.

The unaffordability of universal healthcare is a myth. The Lancet has published a paper showing how a single-payer healthcare system in the US would save $450bn in taxpayer dollars, as well as 68,000 lives, every year. Considering the federal government is already spending $10,500 per capita on healthcare, this reduction in pricing would allow for greatly increased access to healthcare. Despite these figures, Sanders has often had his Medicare for All plans lambasted as being too radical. But it was not until the rise of the Cold War that such socially beneficial policies were scolded for being too communist. Celebrated postwar president Harry Truman pitched the idea for universal healthcare in 1949. More recently, Jimmy Carter had plans for universal healthcare during his presidency, and continues to write about the issue.

Trump, to avoid direct responsibility for the containment of coronavirus, placed vice-president Mike Pence in charge of tackling the disease, a tactic he often employs when seeking to avoid criticism for failed plans – something which former House speaker Paul Ryan bore the brunt of when laying out the administration’s new healthcare plan. Let’s hope Pence’s plan to combat coronavirus is not limited to thoughts and prayers, like his former plan to treat HIV in Indiana, particularly since Trump continues to seek a “miracle” in combatting the virus.

Avoiding scientific reasoning has become a trend with the current administration. In 2000, Pence proclaimed he did not believe smoking causes cancer, as well as having previously promoted conversion therapy. Pence infamously said: “Frankly, condoms are a very, very poor protection against sexually transmitted diseases.” Besides the fact Pence is not a doctor nor a scientist, pushing him to be in charge of managing a global emergency is a recipe for disaster.

Similarly, Trump has used the coronavirus epidemic to reaffirm some of his campaign pledges. Going against science, to combat coronavirus the president tweeted that “we need the Wall more than ever”. The first case of person-to-person spread of the virus in the US was from an individual returning on a flight from Wuhan, China. No wall could have prevented that.

To budget for a coronavirus response, Trump plans to cut funding to winter heating assistance, as the virus has become the latest excuse for his war on benefits. It has been well documented that viruses such as the influenza virus and coronavirus are transmitted better in colder conditions, which is partly why they are so prevalent in winter. And amidst the collapsing economy, Trump has also pushed forward with his plans for a payroll tax cut, likely to benefit only the most affluent workers and also undermine Medicare and social security, both of which are dependent on those taxes and vital to effectively managing coronavirus.

Echoing the Reagan era’s zenith of minimising government, promoting private industry and battling social services, Trump’s 10-year budget plan proposes cuts to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health and other agencies. Despite the CDC’s crucial role in containing coronavirus, Russ Vought, Trump’s acting director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, doubled down on the proposed cuts. Without effective disease prevention in the future and a lack of universal healthcare, coronavirus and future pandemics are likely to uncontrollably spiral. Successful treatment and prevention of similar infectious diseases will remain a parable for as long as the fallacy of unaffordable universal healthcare coverage persists.

With the number of Americans qualifying for effective healthcare dropping, the impact of coronavirus, should it spread, is likely to affect America’s most vulnerable, and Big Pharma will seek to make a quick profit once more. To avoid any catastrophes in the future, a presidential candidate seeking to regulate healthcare providers, the pharmaceutical industry and provide healthcare access to all should be considered. Universal healthcare coverage should be available sooner rather than later, otherwise, we could all suffer the consequences.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments