Cervical cancer screening is at the forefront of preventative medicine – but at what cost?

It’s widely acknowledged by the medical profession that some women are being treated for a cancer which they may not have – and this treatment can be traumatic and damaging, writes Jessica Brown

You might’ve felt nervous when you went for your last smear test, but you probably persevered, knowing it was the right thing to do. That’s not a coincidence – it’s the consequence of carefully curated messaging around the cervical screening programme.

“Research suggests it can be better to set people’s expectation that there may be some discomfort, because then it may be less of a shock,” says Sophia Lowes, health information manager at Cancer Research UK.

“People can respond better to any pain they might experience because they’ve been prepared for it. We don’t want to put people off, but need to make sure they’re informed, which is a fine balance.”

Navigating this balance is crucial. Cervical cancer a preventable disease but more than 3,000 people are diagnosed with it every year in the UK, and only half will survive.

Read More:

However, thousands of people who have further preventative treatment following their smear tests suffer complications they say are being dismissed by doctors. They argue that this balance between telling people what to expect but not putting them off, is dangerously distorted. Sometimes only the correct information, free from distortions, will allow people to make the right decisions for themselves.

Everyone who’s had a smear test in England over the past year has been tested for the 30 cervical cancer-causing strains of HPV, the most common STI, which cause around 99 per cent of all cases. If the immune system doesn’t clear them, they can cause pre-cancerous cell changes within a few years.

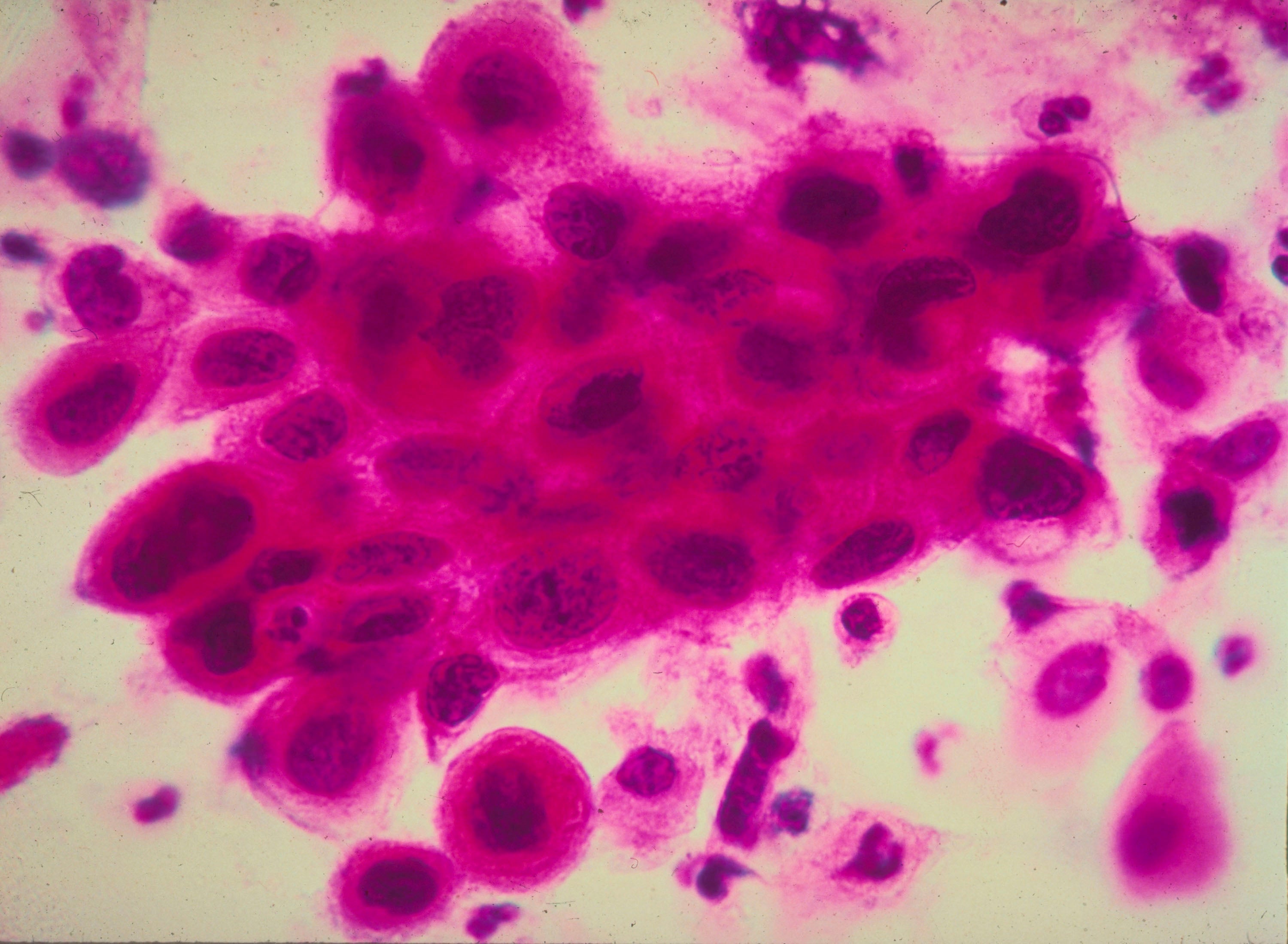

National HPV screening replaced “cytology” tests after trials showed it more accurately detects who’s at risk of developing cervical cancer. The cytology test, where patients’ cells are looked at under a microscope, is now only carried out on those who first test positive for cancer-causing HPV.

Any cell changes are then graded either low or high. Around four in five people with a positive HPV result and high-grade changes will have pre-cancerous cells. Those with healthy immune systems will usually clear the HPV virus within nine months, but there’s no test that shows whether someone will be in the one of five who don’t. Therefore people are being treated for a cancer they may never have.

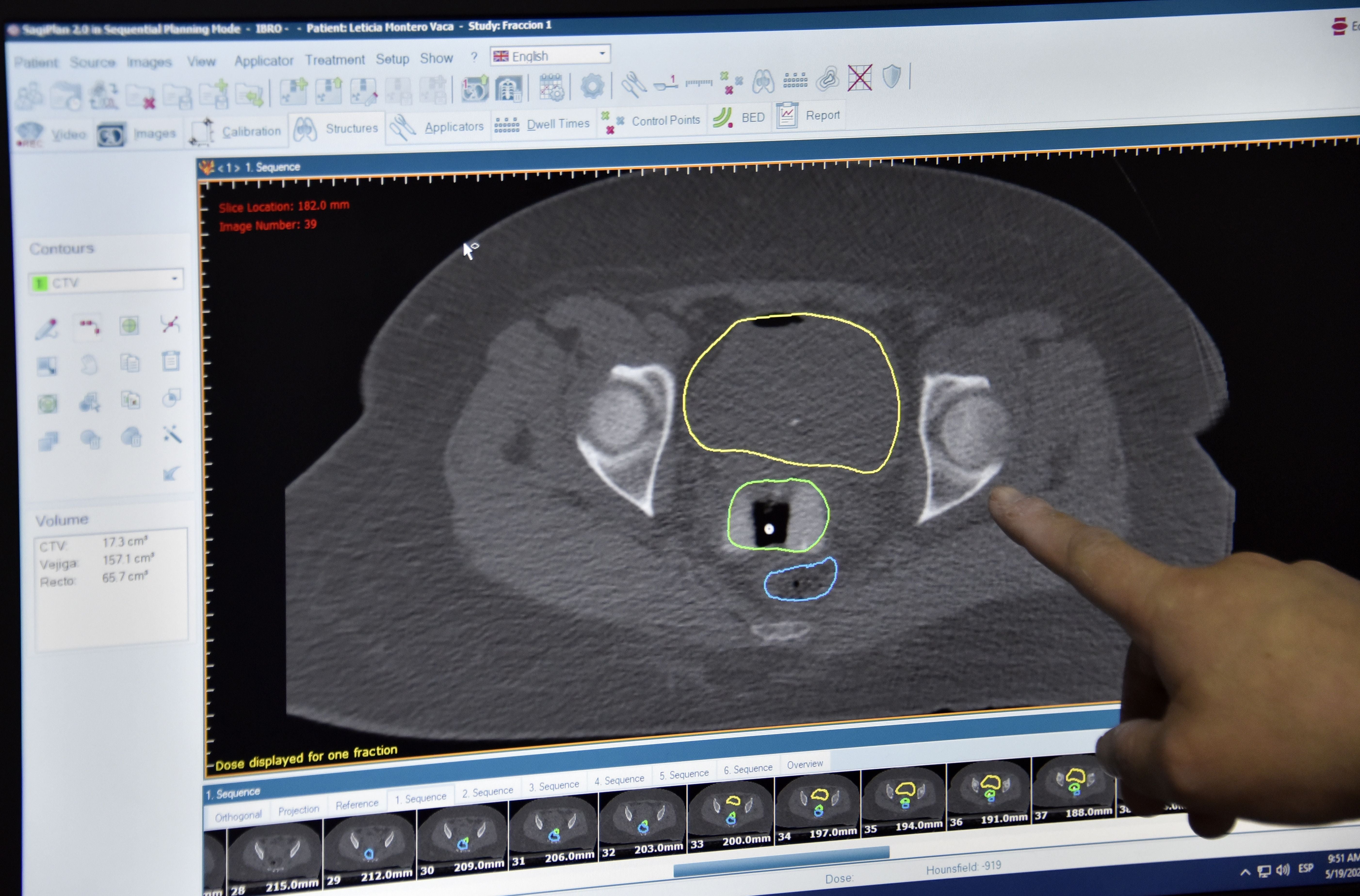

Abnormal cells don’t usually turn into cancer unless left untreated for decades, but those with high-grade changes are referred to their local hospital’s colposcopy clinic for examination, and often, further treatment.

Clinicians examine the patient’s cervix in a procedure similar to a smear test, and will either treat them immediately, or take biopsies of the cells first. Patient’s cells are graded low (CIN1), medium (CIN2) or high-risk (CIN3). Now that doctors are also armed with a patient’s HPV status, they are more inclined to treat, rather than watch and wait, according to research.

Each year, 22,430 people in the UK have further treatment, which has contributed to a reduction in deaths from cervical cancer, which have almost halved in the past 20 years in the UK – although, it’s impossible to say how much of this is due to national screening.

The most common treatment is the large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) procedure. Nine in 10 people who have the LLETZ procedure, during which the cervix is numbed with local anaesthetic and a wire loop cauterises a layer of the cervix, don’t have cell changes again.

“Many women who have LLETZ probably wouldn’t have got cervical cancer,” says specialist nurse Jean Slocombe. “But because we don’t know who’ll develop cancer and who won’t, we offer treatment to everybody with high grade cells.”

Pregnancy aside, of 100 people who have LLETZ, around 85 experience bleeding afterwards, 67 people experience pain and up to 14 will get an infection

LLETZ is already carried out on more people than desired, and the new HPV smear test picks up more pre-cancerous cases than the previous method. Peter Sasieni, professor of cancer prevention at King’s College London, predicts this will lead to a rise in the number of people referred for further treatment over the next five years.

Patients are warned about the risks associated with LLETZ, including an increased risk of miscarriage in the second trimester, and pre-term birth. Sadly, the average age patients are diagnosed with pre-cancerous cells is 30, just one year older than the average age people in England give birth to their first child.

Andreas Castanon, senior epidemiologist at King’s College London, has found no increased risk to those who have less than 10mm of their cervix removed. Only around 20 per cent of all LLETZ procedures in England take away 10mm or more, which makes it responsible for 2.5 per cent of all preterm births.

Castanon says his findings have fed into recommendations to make doctors aware they need to minimise the amount of tissue they remove. Nevertheless, anyone who’s had the LLETZ and goes on to conceive is advised to tell their midwife.

There’s a procedure that can halve the risk of preterm birth in cases where the procedure has made the cervix weaker. But this procedure, where a stitch is placed around the cervix to keep it closed, comes with risks, too, says Sarah Stock, clinical career development fellow at Wellcome Trust and honorary consultant of maternal and foetal medicine.

“It can cause bleeding, damage to cervix, rupturing membranes or can cause miscarriage when you put the stitch in,” she says. “It’s not a good idea to do unless absolutely necessary; it can do more harm than good if it’s not done carefully.”

Pregnancy aside, out of 100 people who have LLETZ, around 85 experience bleeding afterwards, 67 people experience pain and up to 14 will get an infection. Up to 14 people will develop cervical stenosis, where the passage between the womb and vagina becomes blocked.

Patients are usually warned about these risks and side-effects, but thousands experience dozens of other debilitating side-effects that aren’t mentioned. A third of people, for example, will feel pain during or after sex following the LLETZ. For one in five of these people, the pain will go on for more than five years after treatment. Just over one in four will bleed during or after sex.

Some patients say the LLETZ makes their periods more painful, including Tina (not her real name) who underwent a cone biopsy, similar to a LLETZ, last summer under general anaesthetic.

“I wasn’t given much information about the side effects of the procedure. The nurse said the procedure was painless and recovery would be quick.

“When I woke up from surgery, I found out they did a cone biopsy instead of LLETZ, which wasn’t discussed during any of my appointments, and also a biopsy of my vulva, which I only found out a couple of weeks ago during my follow up smear.

“Upon waking I had horrendous pain, but was told by the doctor I shouldn’t be in that much pain. He gave me painkillers and told me to go home. I ended up in hospital three times after that with severe bleeding. I had to have my cervix stitched and silver nitrate applied to stop the bleeding. I lost so much blood that I struggled to walk without being dizzy.

“Even now, six months later I’m still getting random pains and my periods have become so heavy and painful. It was really traumatic, and I think about it a lot.”

Tina isn’t alone in feeling traumatised by the procedure. More than two thirds experience anxiety afterwards, and almost a quarter feel depressed. But the mental impact especially is massively overlooked, across primary and secondary healthcare, says Imogen Pinnell, head of information at cervical cancer charity Jo’s Trust.

“People are feeling more strongly that they’re left in limbo. It’s this weird in-between state where they don’t have cancer but they’re still going through treatment and monitoring and the physical and psychological effects they can bring, but society doesn’t tend to talk about them.”

“It’s unique to have that stage of cell changes,” says Pinnell. Most of the time you either have cancer or you don’t, and you don’t have the chance to prevent it. But it’s this lack of awareness, of the impact of cell changes, that feeds into the issue of a scarcity of information, support and communication.

One way to limit trauma is to offer patients a general anaesthetic, like Tina, instead of local. But it seems many patients aren’t given this option. Andreas Obermair, gynaecological oncologist and professor at the University of Queensland, was trained to do LLETZ in both outpatient clinics, using a local anaesthetic, and in operating theatres with patients under a general anaesthetic. But after seeing how stressed outpatients were, he vowed to do every procedure under general anaesthetic as soon as he finished his training.

“I declined to do LLETZ in an outpatient setting,” he says, “I believe it’s bloody insane.”

It’s cheaper and quicker to do the procedure in an outpatient setting with a local anaesthetic, Obermair says, which is where the attraction comes from. “But the vast majority of women want to be put under. In the outpatient clinic, there’s more pain and anxiety – it stresses me out as a surgeon. I don’t want to do that.”

There’s a growing awareness among some professionals that fewer people should be having LLETZ. There’s no question CIN3, which is the closest stage to cancer, should be treated, but CIN1 and CIN2 can regress, says Philippe Mayaud, professor of infectious diseases and reproductive health at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. But it seems there are inconsistencies regarding who doctors treat.

Two weeks after she had the LLETZ last year, Leah, 33, went for an hour’s walk, and when she got home she started bleeding heavily. She had to have a second procedure to insert gauze that stopped the bleeding.

“When they were putting it in, I felt like I was being violated,” she says. “I was told my recovery period started again. I was signed off work for three weeks, which I mostly spent on bed rest, and i finally felt normal again two months later.”

“The whole thing has really distressed me. My first three periods afterwards were unbearable – I nearly fainted with the first one.”

She’s also worried about whether the procedure will affect her if she decides to have a baby in the future, but doctors didn’t ask her if this was in her plans. “I’m not desperate to have children but if I meet someone soon there’s still a chance,” she says.

I don’t feel the same level of arousal with sex now, it’s just different, and sometimes it hurts. I wasn’t told it could affect your sex life or give you any symptoms afterwards

Leah says she isn’t the sort of person to ignore a doctor’s recommendations, but she now wonders if the LLETZ was the right thing to do. She’s waiting to get the results from her follow-up smear, to make sure the abnormal cells were successfully removed.

“I’m worried about it coming back,” she says.

But Leah was told she only has CIN1. “All of the side-effects could be reduced, along with the number of people having LLETZ unnecessarily, if we used tools that tested to see how the HPV is behaving and if it’s likely to become more aggressive,” says Mayaud.

One way to do this would be to test for methylation, which can switch on cancer-causing genes, Mayaud says – but while this test already exists, it needs more research to prove its effectiveness.

“It’s bad luck to get cervical cancer, but at the moment we don’t know what that lottery is. We don’t have good tools to say a person could wait another five years, so it’s easier to treat earlier in ways that could have biological and psychosexual consequences that people pay little attention to.”

Some people only realise after they’ve had the procedure, that they could’ve perhaps waited to see if the cell changes reversed. Debbie Maton, 62, had LLETZ last April. She started suffering with hot flushes, after never having them during the menopause, and her sex life completely changed.

“I don’t feel the same level of arousal with sex now, it’s just different, and sometimes it hurts. I wasn’t told it could affect your sex life or give you any symptoms afterwards. It’s affected how I feel about myself. It’s angered me that I only had CIN1 and CIN2. I didn’t need to have that operation, but I’ve got to live with this now.”

Sasieni argues that any side-effects beyond what patients are warned about are probably a coincidence, and that it’s always worth doing. “Far more women are being treated than would develop cancer,” Sasieni says, “but we feel, for most women, treatment is minor enough that we’d much rather they have it than wait to get cancer.

“We feel the harms are outweighed by the benefits for the majority. There wouldn’t be a national screening programme otherwise.”

Kris Lynn, 30, tells me she’s seen a common theme in Facebook support groups of a lack of informed consent. “If presented with the choice of the complications I have now and risking cancer, I may have very well made the same choice. But that is my choice to make,” she says. She puts this down to the field being overwhelmingly male.

“I don’t believe that doctors are out to get us; I think women’s healthcare is overlooked and primarily this care is provided, or taught, by men. It’s not the procedure, it’s the lack of information we’re given because someone without a cervix doesn’t feel these side effects are worth mentioning.”

It’s widely but quietly acknowledged by the medical profession that more people than necessary are having treatment

Historically, data from medical studies hasn’t included differences between male and female bodies, and experts argue we haven’t fully evolved from the days when conditions such as endometriosis are often overlooked as “hysteria”.

“Gynaecologists are increasingly female, but not surgeons, and men cannot talk about what they don’t understand, in terms of reproductive organs. All surgeons check for cervical competence – the ability for the patient to carry a baby – even if they don’t understand all the psychological connections, but that aspect probably suffers,” Mayaud says.

It’s no secret that healthcare is historically tailored to men more than women, says Pinnell. “We’re keen to see more informed care; the thread that follows from screening all the way to the procedures we’re talking about are incredibly invasive. It all comes back to having clear guidelines and consistency, and raising awareness that all the things people are feeling are not in their heads. It’s a very real thing that can impact people for years.”

One consensus among people the charity has spoken to, says Pinnell, is a lack of consistency with what they’re told before and after their procedures. “We want everyone to have the same experience when they’re in the colposcopy department, one that doesn’t depend on a postcode lottery, where they have time and are given the space to process everything,” she says.

Thankfully, far fewer people will need the LLETZ in years to come. England's national vaccine programme protects against four types of HPV that cause more than 70 per cent of cervical cancers in the UK. Since it was introduced a decade ago, more than 80 per cent of women aged 15 to 24 have been vaccinated.

Read More:

But in the meantime, it’s widely but quietly acknowledged by the medical profession that more people than necessary are having treatment, and that this treatment can be traumatic, and damaging in more ways than we acknowledge.

While writing this article, I came across a leaflet tucked away in my desk drawer from December last year, when I had the LLETZ procedure. I’m reminded that, while it was traumatic, while I did have complications and felt like I wasn’t always listened to by doctors, I had it relatively easy.

Every patient I’ve spoken to is enormously grateful there’s a procedure that can prevent cervical cancer. We just hope that, soon, the communication around it can be as advanced.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments