Clothing brands need to learn how to embrace post-cancer bodies

Maternity brands that once hid baby bumps now embrace the chance to showcase them. But cancer patients rarely want to flaunt their changing bodies, writes Susan Gubar, and the industry keeps its distance

The conventional pants had been replaced by pull-up leggings long ago, but now the blouses wouldn’t close. Except for a few treasured tops that might fit my friend Julia, I popped the rest into a bag for Goodwill. A physical and psychological trial, living with cancer also poses the ongoing challenge of finding apparel for bodies altered by treatment.

During more than a decade as a cancer patient, I have gone through multiple operations, treatments and procedures. Every time doctors reshaped my anatomy, I found myself flummoxed in my closet. After debulking surgery for ovarian cancer, anything tight around the midriff hurt. At chemotherapy infusions, most garments hung off my skeletal frame. Interventional radiologists left me with a long, thick tube emerging from my right buttock and attached to an output bag.

Attire confounded me, so I resorted to sweatpants and rarely left the house. Yet I hesitated before purging my teaching togs. Perhaps I could recover my earlier body and my previous life as a professor. The old garb served as a promise that cancer would not alienate me forever from my former self.

Recurrently, I said goodbye to that pretty thought. When Julia hauled off my favourite shirts, the farewell finalised. I removed every item that did not conceal the port embedded in my chest, the ostomy pouch glued to my belly, and the skinny appendages as well as the thickened trunk that somehow emerged after four years of standard treatment and then another seven years on a targeted drug in a clinical trial. I was feeling quite sorry for myself when I told my husband that I had to go shopping.

“I remember shopping for Mary-Alice’s birthday,” he said. He was referring to his first wife who died too young of breast cancer. “I found a blouse, but she could not handle buttons anymore.” A courteous man, he always clarifies my thinking without calling me the ditz that I most certainly can be.

Acknowledging the gift of 11 post-diagnosis years, I sat at my laptop and went on a virtual shopping spree. I was looking not for T-shirts with witty logos but for solutions to problems that cancer patients encounter.

After lengthy searches, my No 1 find: “chest-access shirts”. For those with a port, this shirt has a zipper on the left- or right-hand front. No need to bare your breast in a public infusion room ever again. Just unzip the diagonal zipper from the collar to the area near the armpit and a flap unfolds. When I wore it for the first time for a blood draw in the hospital, a seasoned nurse marvelled: “It’s way beyond cool. It’s awesome!”

A second discovery: “catheter pants”. These trousers, which might be useful for people dealing with prostate or bladder disease, hide an output bag strapped to the leg while keeping it accessible. A long zipper or Velcro edging opens down the side seam from the waist to the ankle so that a urine pouch can be drained or changed. What they sacrifice in trendiness they make up for in convenience.

Though both garments were welcome news, I already knew about the ostomy paraphernalia on the web, which includes stealth belts and bands that don’t work for me. Pressing against the plastic bag on my belly, they cause what I euphemistically call buildup and blow out. The best ideas came from patients who underwent abdominal or colorectal surgeries recycling trousers created for other purposes: maternity pants with elasticized tummy panels and surgical scrubs with drawstrings.

But I am a bad shopper, both online and off. Perhaps some of you readers can assist correspondents who have asked me about lymphedema wraps that don’t look like bandages, bras for one breast, and footwear for feet with chemo-related neuropathies.

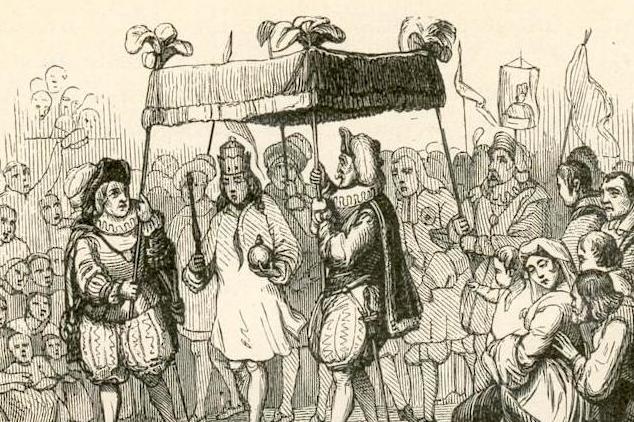

Stymied at finding camouflage, I started to wonder: whom am I trying to kid? The idea of delusional sartorial pride brought to mind Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Emperor’s New Clothes. Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee probably did not consider this tale when he composed his influential book about cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies, but it seemed somehow pertinent to my perplexity.

With our concavities and bulges, scars and bags, prostheses and appliances, skin sensitivities and problems handling buttons, men and women coping with cancer comprehend all too well how we look unclothed

The swindlers in Andersen’s tale claim to weave fine fabrics that, they say, will be invisible to onlookers unfit for public office. Government officials and then the emperor himself praise the nonexistent outfits because they don’t want to appear incompetent. As the naked leader parades himself in the illusionary finery, one child and then the townspeople realise that “he hasn’t got anything on”. Still, the monarch continues to strut about while his obsequious attendants gather up the royal train that is not there.

Andersen satirises the deceptions of hypocritical politicians and those who kowtow to them, even as he suggests that their charades may not be halted by truth-tellers: a timely admonition.

However, I take away a humbler point, namely the powerful protection of visible, palpable costumes. Neither the emperor nor the emperor of all maladies has inspired the creation of new wardrobes. Andersen’s vain monarch and his sycophants refuse to admit that no apparel has been created for him, but many patients know that designers and manufacturers haven’t found it profitable to outfit us in widely advertised or available garments.

With our concavities and bulges, scars and bags, prostheses and appliances, skin sensitivities and problems handling buttons, men and women coping with cancer comprehend all too well how we look unclothed. Undergoing recurrent physical exams, we experience what it means to be exposed and embodied … maybe more than healthy people do. Manufacturers of maternity clothes who once hid pregnant bodies under huge tents now embrace the chance to showcase the bump. But cancer patients rarely want to flaunt our changing bodies, and the apparel industry tends to keep its distance.

Fully cognizant that cover-ups are just that, I nevertheless need some help heeding Elizabeth Bishop’s sardonic injunction to an avatar of herself, the hairless and sick animal in her poem Pink Dog: “Dress up! Dress up and dance at Carnival!”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks