Forget Grand Theft Auto – Heavy Rain was the most sadistic video game ever made

Quantic Dream’s slow-going PS3 noir felt like a breath of fresh air when it was released 10 years ago, but the game’s leering sexism and disturbing violence have left it with a complicated legacy, writes Louis Chilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I should have adored Heavy Rain. As a teenager who grew up obsessively watching police procedurals like The Shield and NYPD Blue, and noirish serial killer films such as Se7en and Zodiac, I felt like Heavy Rain was designed specifically for me. Here was a PS3 game that let you experience a deadly mystery for yourself, placing you in the shoes of four interconnected characters who orbit a spree of child murders.

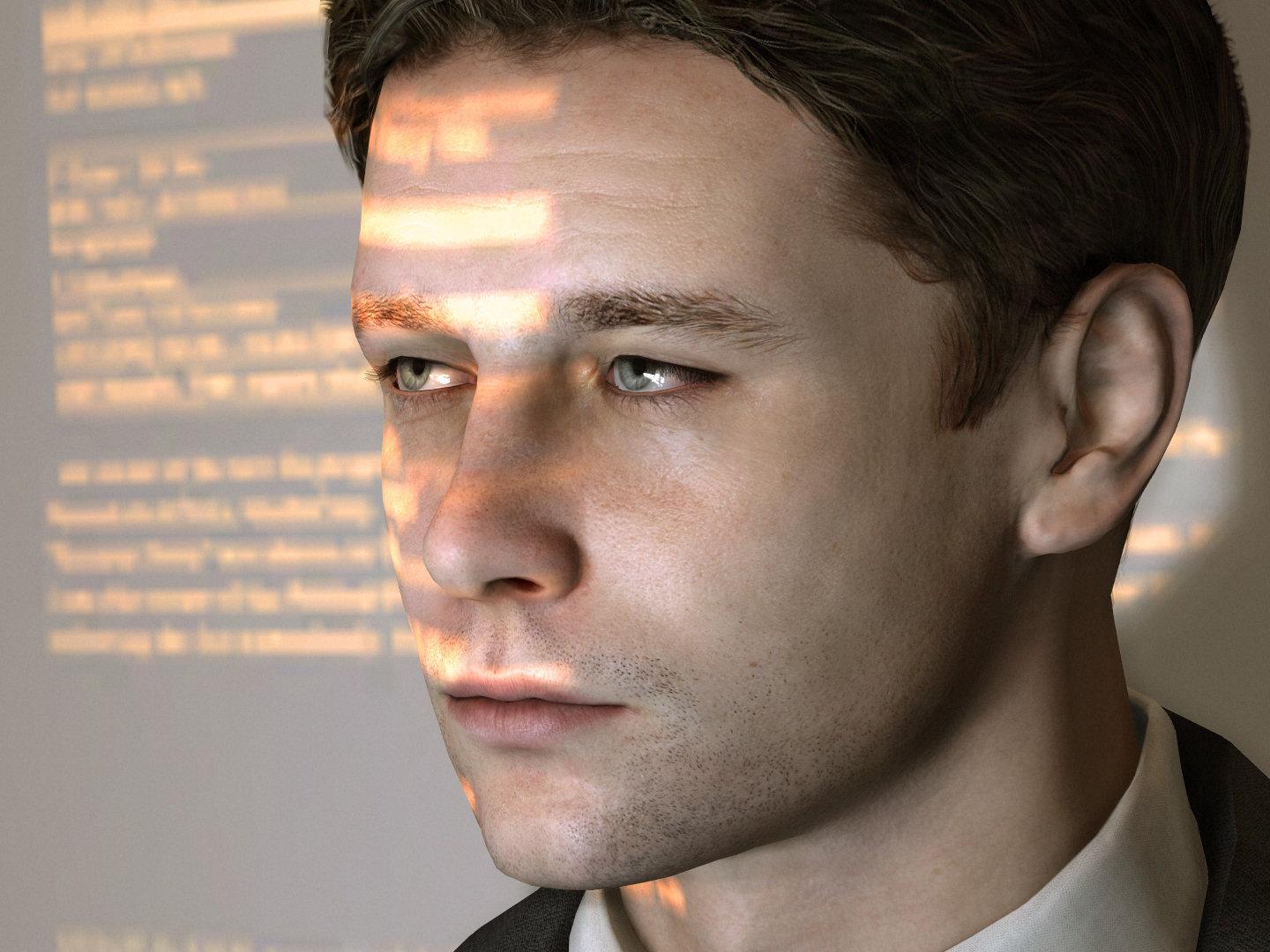

Released 10 years ago on 23 February 2010, Heavy Rain was described ubiquitously as an “interactive film”. That is to say it was a game with no real technical challenge, where enjoyment was derived from the strength of the story, the knowledge that you can pull the narrative in different directions or nudge it off-course with an errant judgement. There was no “Game Over” screen if one of your characters died; the story simply continued without them. This was exactly the sort of game I had been craving.

From the very first sequence in the game, though, something felt wrong. Ambition leapt off the screen, sure, but also cruelty. In the sequence, you play as Ethan Mars, a married father of two, as he loses one of his young sons in a shopping mall. As Ethan, you wander around, shouting his son’s name, scanning the throngs of people for any trace of his boy. Eventually, he is spotted; walking out into the street, Ethan arrives in time to witness his son be hit and killed by an oncoming car.

It’s a tense scene, lent impressive cinematic heft, but it soon becomes clear that the child’s death was mostly just a pretext to give Ethan some serious psychological baggage, raising the stakes of the game’s central storyline in the process. Heavy Rain is a game that deals in emotional manipulation, and it has a fearsome appetite for collateral damage.

The ticking clock at the core of the game is Ethan’s other son, who, years later, is kidnapped by the “Origami Killer”, an elusive serial killer who murders children by drowning them in rainwater. Happy to draw a second calling card from the deck, the killer also leaves tiny origami figures on the bodies of his victims. Silence of the Lambs it ain’t, but this faintly ludicrous premise seems right at home in some of the pulpier corners of the serial killer genre.

Many critics lavished praise on Heavy Rain when it was first released. Most of the few dissenting opinions focused on aesthetic or technical concerns, such as the game’s motion-capture acting performances, which varied in quality, or the suffocatingly slow pace of certain gameplay segments. Nonetheless, the game won a host of industry awards and has now sold over 5m copies (when its 2016 PS4 re-release is taken into account), making it one of the PS3’s highest-selling original properties.

Throughout the game, you control four characters. In addition to Ethan, there is journalist Madison Paige, FBI profiler Norman Jayden and private eye Scott Shelby – all of whom conduct their own separate investigations into the killer’s identity. There’s a certain amount of sadism at play in Ethan’s story, which finds him having to complete a series of tasks mandated by the killer in order to save his child. These escalate from driving the wrong way down a motorway, to electrocuting himself, to severing his own finger, to murdering an innocent man, and, finally, to suicide.

The whole thing sits somewhere between the Book of Job and the Saw franchise. Fail even one of the tasks and there’s a good chance Ethan’s son will drown at the game’s end. Heavy Rain is never mentioned in the same breath as the scandalising Grand Theft Auto or Manhunt 2, but perhaps it ought to be. At least in Grand Theft Auto, children are off-limits.

Indulgent cruelty is far from the game’s only problem, however. FBI agent Norman spends the game suffering withdrawals from a fictional drug called “triptocaine”. His is intended to be a narrative of addiction, which the player can either opt to overcome, or succumb to, depending on the merest press of a button. His drug habit, however, is treated with all the worst cliches, and the withdrawal tends to surface in such jarring bursts that it’s always tempting to trigger a relapse just to end the scene quicker.

Madison Paige, the game’s sole female player-character, is continuously leered at by the camera; it takes only a few minutes of playing as Madison for the game to ask her to undress and shower. One low point sees her re-routed to a seedy nightclub for a side-quest of spurious journalistic value. After applying makeup and ripping her skirt, she inveigles her way into the club’s back office and stripteases to land what she can only assume is the big scoop. Another crass non-sequitur sees her drugged and tied up in a man’s basement.

Madison is one of few women of note in the game; the second-biggest female role takes the form of Lauren Winter, a sex worker whose son had been murdered by the “Origami Killer” years before. Women in Heavy Rain are defined almost entirely by their capacitiy for sex and motherhood. Being charitable, I suppose you could interpret the game’s sexism as a misjudged homage to the insipid female archetypes found in old (and many not-so-old) detective films. But there is no reason to be charitable at all.

Heavy Rain was masterminded by David Cage, a French game designer who had found critical success in 2005 with the release of the PS2 and Xbox game Fahrenheit. In the decade since Heavy Rain’s release, Cage’s company Quantic Dream has released Beyond: Two Souls, a supernatural thriller starring Ellen Page and Willem Dafoe, and Detroit: Become Human, a visually breathtaking sci-fi parable about discrimination and revolution in a robot-filled dystopia.

Both games carried over features from Heavy Rain: its slow-going gameplay, interactive control schemes and branching narrative arcs. But they carried over its flaws, too: its gratuitous shower scenes and emotional tone-deafness. Opprobrium rained down on Detroit for its wretched stabs at racial-political allegory, with one infamous segment giving a light-skinned android the chance to make a public speech emulating Martin Luther King. In the light of those problematic misfires, it seems that Heavy Rain’s ugliness is not just surface deep, but part of the very fibre of its making.

Heavy Rain’s success proved just how desperate audiences were for mature, complicated crime storytelling in games – they still are to this day. But as time goes on, people will look back less and less fondly on Heavy Rain’s cruelty, its sexism, its stigmatising attitudes to mental illness and sex work. Even now, with just a decade having passed, Heavy Rain often feels like a curio from another age. Subsequent games have imitated and improved its gameplay formula, like the great B-movie-inspired horror Until Dawn. With any luck, others still will keep building on the game’s successes, leaving its failures to trickle away with the rain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments