Initially criticised by Hamilton and Verstappen, how the halo has saved lives in Formula 1

Guanyu Zhou’s harrowing crash at the start of Sunday’s British Grand Prix was another victory for Jean Todt, the former FIA president who pushed for the halo’s introduction in 2018

On the eve of the 2018 Formula 1 season, Jean Todt was receiving pelters from all angles. The then FIA president was passionately defending the introduction of the halo cockpit protection device – and the aesthetic change it would bring to single-seater racing cars – from hardline traditionalists. Of course, the true irony was that, in reality, it was literal pelters in the direction of drivers in the danger zone which the French supremo was primarily concerned about.

Guanyu Zhou’s harrowing crash at the start of Sunday’s British Grand Prix was another victory for Todt and the FIA technicians who acted on the concerns of drivers back in 2015. The likes of Jenson Button and Sebastian Vettel were pushing for mandatory head protection, particularly in the wake of Justin Wilson’s death in IndyCar that year and Henry Surtees’s sad passing in an F2 race in 2009. Jules Bianchi also lost his battle in July 2015 after his horrific crash at the Japanese Grand Prix nine months earlier.

Yet in the years since, there have been no driver fatalities in Formula 1. Impressive, frankly, considering the scale of accidents we have seen in recent years with Zhou’s the latest in a long list of crashes where the consequences could have been fatal.

While in the 2018 build-up Toto Wolff remarked on the halo, “if you give me a chainsaw I would take it off”, a matter of months later we saw the first instance of its very genuine functionality amid the propelling speed and forces of a Formula 1 car.

At the start of the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, the halo played a vital role in minimising the damage to Charles Leclerc, after Fernando Alonso’s car was launched in the direction of the Monegasque’s Sauber. Leclerc, then 20, avoided direct contact with Alonso’s McLaren due to the halo’s sturdy presence around the cockpit. Wolff was, to some extent, made to eat his words as he said afterwards: “I think the aesthetics are terrible. But having saved Charles from harm and injury makes it all worth it. It could have been very nasty.”

Romain Grosjean’s horrific crash into a metal barrier in Bahrain two years later was another triumph for architects of the halo. Seen the world over given the dramatic fireball, the 67G collision was one of the most dramatic incidents in Formula 1’s 70-year history. Yet there was no fatality. In actual fact, with the halo sheltering the Frenchman’s head and body from coming into contact with the barrier, he scurried out unaided from the ball of flames.

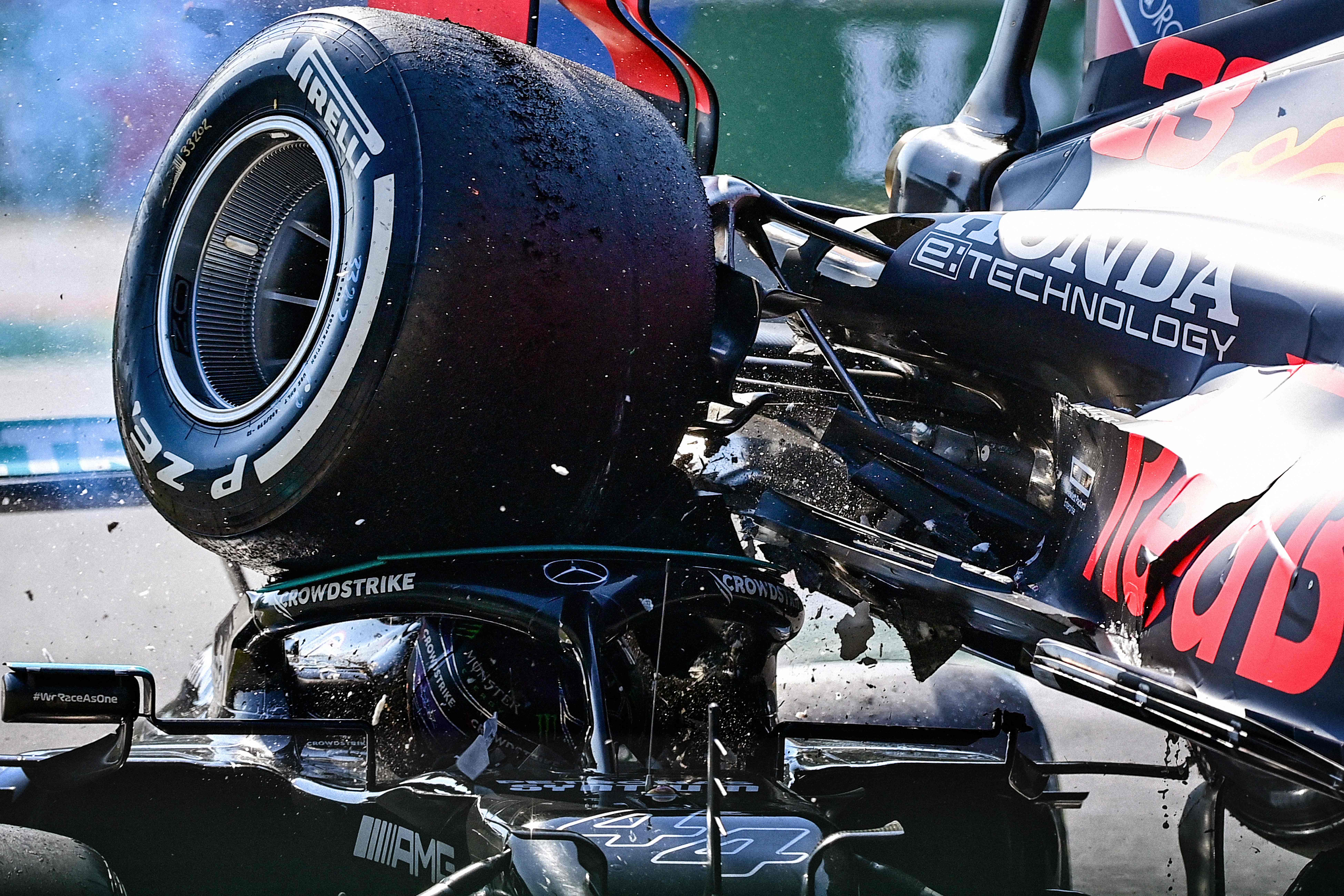

Even last season, the device contributed to the incredible title battle between Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen. Hamilton had in 2016 described the halo as the “worst-looking modification in Formula One history”, with Verstappen commenting that it “abused the DNA” of Formula One.

But when Verstappen’s Red Bull ballooned into the air off the sausage kerb at the first chicane in Monza, straight on top of Hamilton’s Mercedes, the halo and roll hoop protected Hamilton’s head from further damage. The Brit said afterwards: “Thank God for the halo. That ultimately saved me. And saved my neck.”

This time round at Silverstone, with Zhou’s Alfa Romeo careering across the gravel upside-down, his head was protected from lethal contact from the ground below due to the halo’s presence. Following that, with the Chinese rookie hanging in his car between the catch fencing and tyre barrier, he was momentarily trapped inside the cockpit. Trapped, but safe. Again quite remarkably, given the violence of the crash, Zhou escaped without a fracture.

Hours earlier in the Formula 2 race, Dennis Hauger’s car was launched through the air off another sausage kerb – a track aspect which should be evaluated more closely given events in recent years – on top of Roy Nissany’s car, with the halo taking the brunt of the impact.

All three drivers – Zhou, Hauger and Nissany – were shaken following the incidents but such is the power of the halo, all three intend on racing again in Austria in just four days’ time.

By now, all critics of the halo have quite rightly swallowed their medicine. There can be absolutely no doubt of the simple device’s quite supreme powers of protection. Lives have been saved, tragedies prevented, measures justified.

Todt, now the UN secretary general’s special envoy for road safety, timely tweeted on Sunday: “Glad I followed my convictions in imposing the halo, despite a strong opposition!”

Right you are, Jean, right you are.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks