Don’t go there

In his first book, Pierre Bayard argued you needn't read books to discuss them. Now he writes that it’s perfectly legitimate to talk about foreign parts without visiting them

There are few names in the history of travel as glorious and symbolic as that of Marco Polo (1254-1324). Even more than Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama, his name is linked to the idea of adventure and the discovery of unknown lands. He practically symbolises the association of physical courage with knowledge.

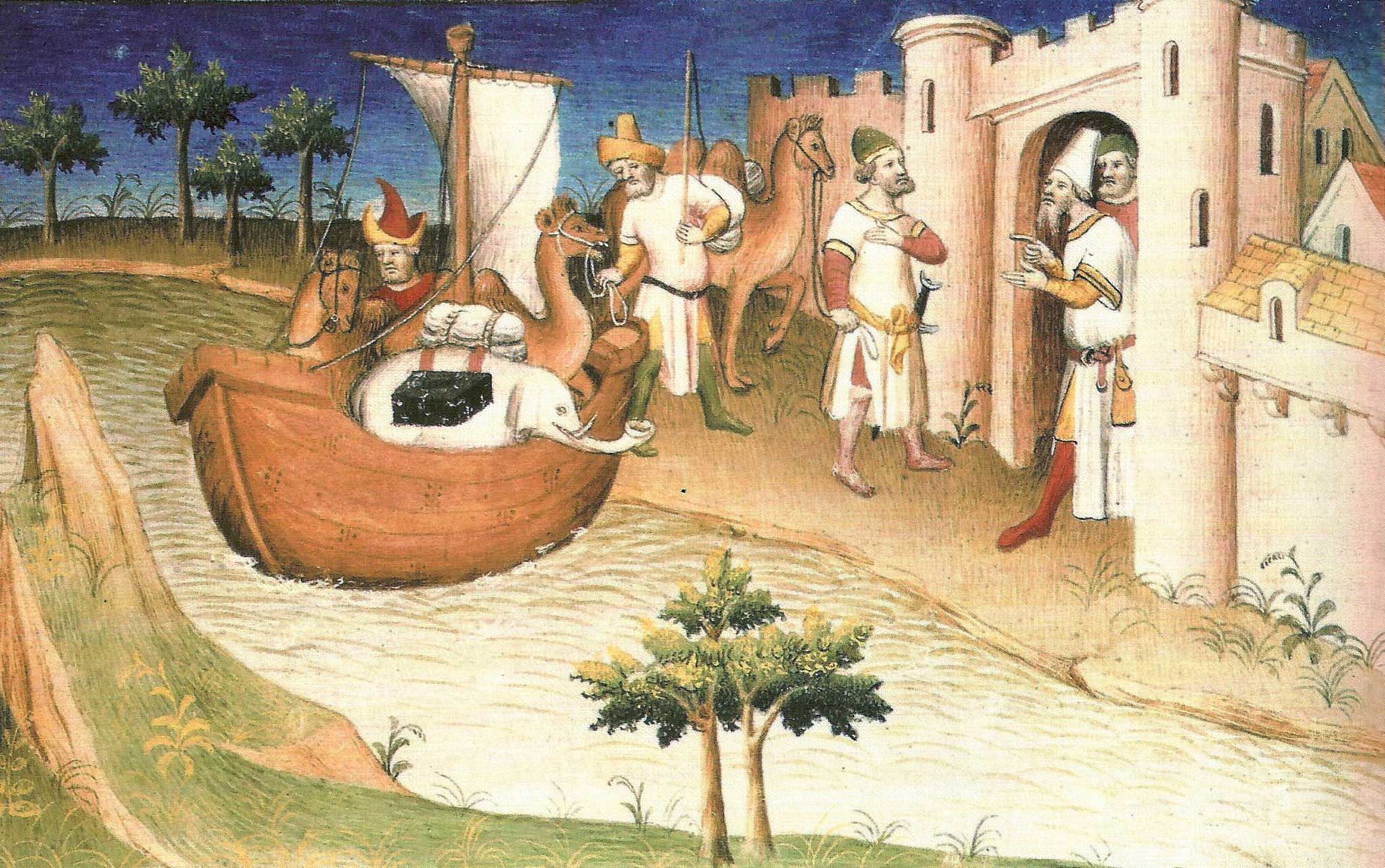

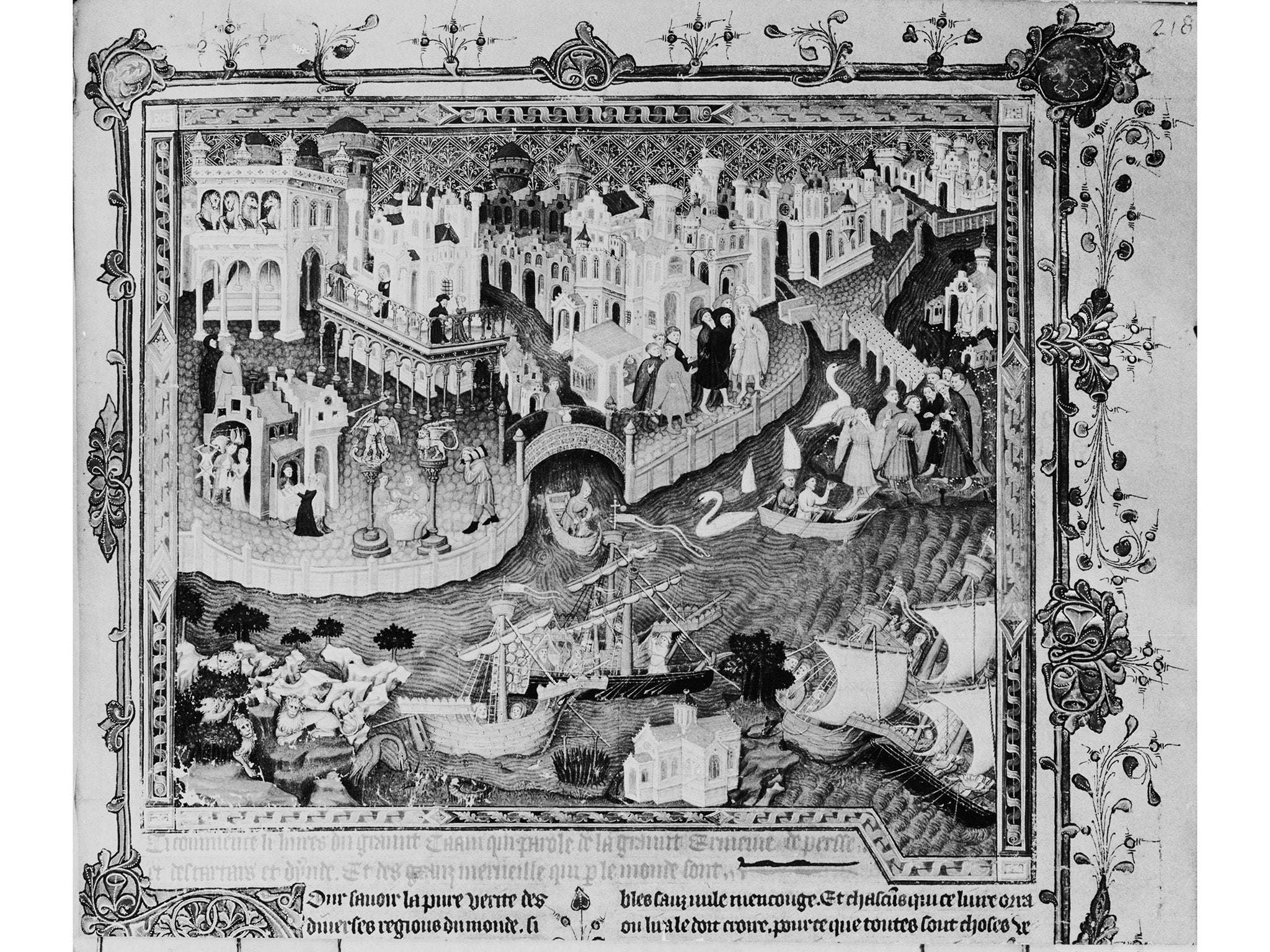

Our private hearing of Marco Polo does not only take into account the journeys he made and his long sojourns abroad but also the particularly well-documented accounts he left behind. It is these, passed down through the centuries by scrupulous copyists, that, being first-hand, give us exceptional insights into the medieval Asiatic world and in particular the Chinese empire, which was largely unknown to the West before Marco Polo arrived and lived there awhile.

The life of this Venetian merchant was an extraordinary adventure. He was 15 when his father and uncle, travelling merchants from Venice, returned from a long voyage in central Asia where they had met the Mongolian emperor Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, who had given them a letter for the Pope.

Two years later, Marco accompanied them when they returned to China and discovered Kublai Khan’s court for himself. He entered into service with the Mongolian emperor and, charged with various missions in China and other Asian countries, he took on increasingly important functions at court. This gave him an exceptionally broad overview of the Chinese empire and its management, as well as of its neighbouring countries.

Gone from his native country for more than 20 years, Polo returned after long peregrinations, and, thanks to a fortune accumulated in China, went on to arm a galley in order to fight in a war between Venice and Genoa. He was taken prisoner during a naval battle and incarcerated in Genoa - where he dictated an account of his travels to a fellow captive, the writer Rustichello da Pisa.

The original text, most likely written in 1298 in Old French, has not reached us, but numerous editions were in circulation in the Middle Ages, and these can give a clear enough impression of its form and content.

And today these editions allow us to access Marco Polo’s fabulous travels with as much of a sense of wonder as his first readers had. Marco Polo’s contribution is actually of vital importance to gaining a complete picture of medieval Asia. He left behind accurate information about all the countries, regions and towns he passed through and described them one by one, from the Middle East to Japan, reviewing the customs of the inhabitants, geography, currency, agriculture and religion.

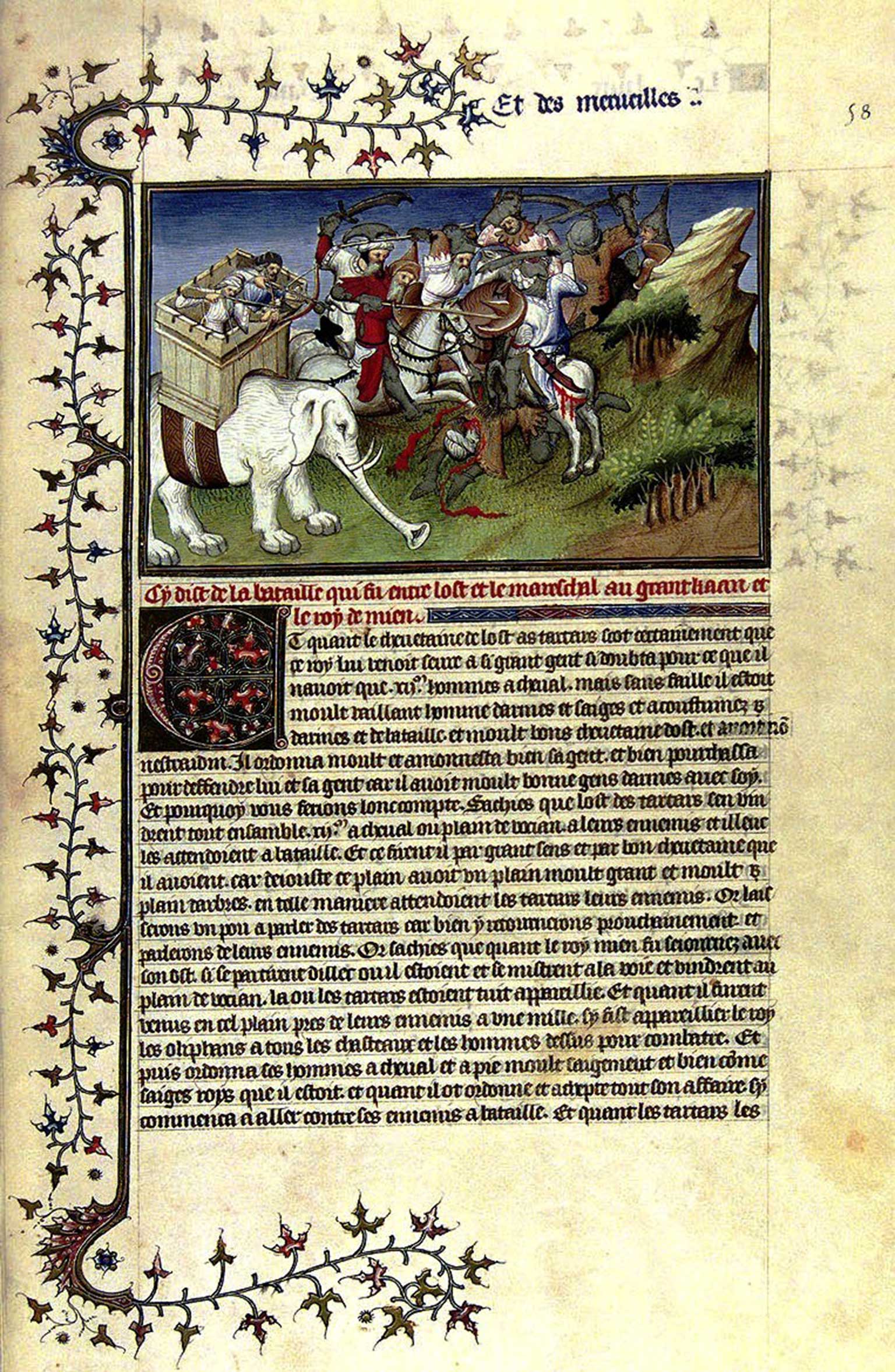

His information is all the more significant because it takes the form of an objective, systematic account. Whatever town or country he passed through, Polo stopped to fill in a comprehensive report, taking great care to note down any factual or scientific information that might be needed by anyone deciding to follow in his footsteps. The country he covered the most comprehensively was China. He lived there for 17 years and knew it through and through. His book is particularly rich in information on the imperial capital and its fortifications, on the palace of the Great Khan, the Mongolian army and its composition, on the distribution of command posts or surprise tactics - one of which was pretending to flee - all of which allowed the Mongols to triumph over their enemies.

He goes into just as much detail about the Mongolian administration. Marco Polo was employed there for a long time and describes its workings exhaustively. The reader learns how the empire was divided up into 12 administrative districts, how mail circulated around the whole empire between the capital and the provinces via a sophisticated messenger relay system, how the empire protected the population from epidemics or famine, and which technical processes were used to mint money.

But Marco Polo’s input isn’t only important for the knowledge it provides on the army or the imperial government. His work also comprises a wealth of well-underpinned information on everyday China and daily life there, from religious practices and celebrations to clothing and food.

Marco Polo’s work offers us a unique first-hand account of the amorous customs of the inhabitants of the countries he travelled through or stayed in. Its power derives both from its narrative quality and the original information it provides. This is particularly the case in the area around Xichang - Marco Polo gives us an unembellished report of the sexual habits of its inhabitants: “I would like to add that, in this region, there is a custom I will tell you about concerning people’s wives. The menfolk do not consider it a disgrace when a stranger or another person dishonours their wife, their daughter, their sister or any other woman in their household; they consider it a great blessing for them to be bedded and they say that, thanks to this, their gods and idols are better disposed and give them an abundance of the riches of this world.”

This is how we learn that, when welcoming strangers into their homes, the inhabitants of Xichang order their wives to satisfy their guest’s every whim and fancy and then voluntarily leave the house and don’t come back until the stranger, who might have spent three or four days there, has left. During this time, the stranger has been able to freely avail himself of all the women living there: “This is why they give their wives with such generosity to strangers and other people, as I told you. Note that when they see that a stranger is looking for a place to stay, everybody is glad and happy to invite them into their homes and, once he is installed, the master of the house goes out immediately and orders his wife to satisfy all the stranger’s desires forthwith. Then, once he has given the command, he goes out to his vineyards or his fields and doesn’t return until the stranger has left. Hence the stranger sometimes stays three or four days in the poor devil’s home, having a good time with his wife, his daughter, his sister or whoever he chooses.” To ensure that his satisfaction is complete, it is important to avoid disturbing the stranger in his pleasures.

The inhabitants of Xichang invented an information system of great simplicity that afforded their guests the necessary peace and tranquillity: “While he is staying there, the stranger’s hat is hung from the window or the door or some other signal is given so that the master of the house knows that the other man is still there: as long as the sign is there, he will not dare return. This custom is practiced across the entire region.”

The Xichang region, however, is not the only part of China where travellers are offered such sexual hospitality. The same goes for “Tibet” [by which he means the mountainous part of Sichuan], where a woman’s value is proportionate to the number of partners she has had before marriage. This functions as an incentive for the women to offer themselves to any overnight guests, going so far as to collect souvenirs so as to be able to prove the intensity of their sex lives to their future husbands:

“The woman with the most medals and trinkets who can show she has been touched the most is considered the best, and a man marries her with the greatest pleasure because it is said that she is the luckiest.”

Of great interest, we learn, for its unexpected revelations about the hospitality and sexual customs of locals, The Travels of Marco Polo is equally fascinating for the descriptions it offers of the fauna of the places traversed, of which the book provides incomparable descriptions in scientific terms. This applies to the passage dedicated to portraying animals on the island of Java, in particular the unicorn, whose exact nature has fuelled debates since antiquity before being definitively established by Polo, who puts an end to the legendary representations: “They have great numbers of elephants and also great numbers of unicorns, which are not much smaller than the elephants. Here is what they look like: they have the same hide as a buffalo, feet like an elephant, and they have very thick, black horns in the middle of their foreheads. The unicorn does not injure with its horn but with its tongue since it has lengthy spines on its tongue. It has the head of a wild boar and always carries its head pointing downward. It likes to dwell in lakes and bogs. It is a very ugly creature, not the kind one could capture with the breast of a young virgin as they say at home: no, quite the contrary.”

Just as instructive in scientific terms is the description of Andaman Island, whose inhabitants have certain morphological features that were revealed only by Polo: “Andaman is a very large island. Its people don’t have a king, they are idolatrous and are veritable wild beasts. I should add that the men on this island of Andaman have dogs’ heads, their teeth and eyes too: their faces perfectly resemble large mastiffs. They have large quantities of spices, they are very cruel because they eat everything they can catch as long as it is not their own kind.”

And the same applies to the island of Mogadishu and certain of its creatures, about which the travelling merchant provides crucial information: “The griffin is so strong it seizes an elephant with its talons, lifts it up very high then drops it again, breaking the elephant’s bones, then the griffin sits on top and eats its fill. The people of the island call them ‘rucks’, and they have no other name, so I do not know whether there is a larger bird or whether this bird is a griffin.

Still, it does not have the shape we lend to it - half lion, half bird - but is gigantic and resembles the eagle.” We see the extent to which, in terms of the inhabitants’ customs but also those of animals, Marco Polo’s accounts should be praised for making us change our often overly rigid mental habits and adapt to alternative worlds whose discovery can only serve to enrich us intellectually.

Surprising in what it describes, Marco Polo’s work is also surprising in what it fails to describe, as if the narrator’s focus on certain aspects of the countries he visits is bizarrely accompanied by a prudent reserve about others. First of all, it should be noted that the explorer showed great discretion in China, the country in which he claims to have lived for the longest time. Such great discretion that the imperial archives, which are, moreover, very comprehensive, bear no trace of his passage, despite the fact that he says he was assigned important duties.

Equally astonishing are certain gaps in his account, as though he was suddenly blinded or became distracted at certain moments. It is surprising that someone might describe China for dozens of pages without the slightest mention of the thousands of kilometres of the Great Wall that he is supposed to have crossed at several occasions during his peregrinations.

Though he pays attention to the smallest stories, Polo doesn’t find anything to say about the bound feet of Chinese women, nor about the tea ceremony, nor cormorant fishing. And generally attentive to the linguistic particularities of the places he visits, he doesn’t appear to have noticed the existence of ideograms. All of these improbabilities have led authors of sceptical persuasion – including the sinologist Frances Wood in Did Marco Polo Go to China? – to express certain doubts about his actual presence there. Wood comments that the book appears more like an accumulation of records than the account of a real journey, whose stages, moreover, it would be very difficult to reconstruct from the incoherent information offered to us.

Following her reasoning to its logical conclusion, Frances Wood challenges most of Marco Polo’s travels, advancing the theory that, in reality, he got no further than Constantinople, where his family had a bar which numerous travellers passed through, their stories feeding his reverie. Though we usually recognise the acclaim for his courage and the scientific quality of his information, if we consider the evidence, we see that what Marco Polo did possess was a great deal of imagination - a quality insufficiently stressed by critics of his work.

If we consider this Venetian trader, his women offered to all-comers and his men with dogs’ heads, what he relates and what he omits to say, it is difficult to believe that he did actually go to Kublai Khan’s China at all. Might it not actually be that his text powerfully illustrates the important fact that the travelogue is a favourable place for the practice of fiction - since the reality of Polo’s travels clearly didn’t prevent him from witnessing improbable scenes or being affected by hallucinations sufficiently pervasive that they continued to haunt him during the writing of his account. These scenes are close to the ones that populate dreams, where sexuality crops up constantly when not directly represented, or composite creatures are produced by condensing images, or an ideal world dominated by infantile omnipotence substitutes, in a kind of narrative euphoria, the depressing everyday reality.

This permanent link between the travelogue and the practice of fiction means that we are placed in a different register of truth than in traditional narratives, which are forced to choose between truth and lies. It is a register where fiction - or at least indecision about the authenticity of the reported facts - is considered to play an active role in the narrative and therefore doesn’t shock the reader in the slightest since he accepts the principle.

Actually, it should be noted that this Freudian “other scene” is not an isolated construct but pluralistic. Marco Polo’s accounts functioned equally well in his day because they corresponded to an expectation and belonged within a collective imagination where no one was surprised to come across dog-headed men in their readings. And they continue to be received today as credible documents, even though they seem to have been infiltrated by imaginary beings and fantasies.

What they help to build therefore is a space for reverie, outside of the constraints of science. If Marco Polo’s travels recall the role that fiction plays in every travelogue, they also question the boundaries between travel and “non-travel”. The fact that, centuries after the tribulations of one of the most famous explorers in history, medieval specialists are incapable of coming to an agreement about whether he actually made it to the Far East or whether he wisely remained at home speaks volumes about the difficulty of separating travel from non-travel, and in so doing, the complexity of attempting to grasp the notion of travel with any rigour. In fact, there are many intermediate cases between travel and non-travel - as there are between reading and non-reading - and being in a situation where unknown places are discussed is, in fact, much more common than we think and not limited to the extreme case of travellers remaining in their homes.

This uncertainty about the boundary between travel and non-travel is intimately tied up with the fiction that accompanies any description of a place. The capacity of human beings to imagine things means first and foremost that descriptions linked to real travel should always be nuanced – realising just how much they are mixed up with personal fantasies, whether the author has intended this or not, and that a traveller is capable of recounting in good faith scenes or imaginary locations he has ended up believing in.

Furthermore, this recognition of the active role of fiction in the travelogue presumably dissuades many potential travellers from travelling. They have become aware of the fact that the essential point is the quality of the reveries produced about the places to be visited, plus the narrative force of their account - a reverie and an account that in order to germinate and grow, won’t necessarily gain anything from being founded on an authentic trip.

I have often asked myself where Marco Polo spent the 20 years he disappeared for and what mysterious occupation kept him in the mysterious place he chose as a sanctuary. I doubt, unlike Frances Wood, that Marco Polo ventured as far as Constantinople. His piecemeal knowledge of China can be explained in quite a different way: in talks he had with travellers returning to Italy. I am more inclined to believe that he chose to retreat to a secluded, peaceful place somewhere near Venice.

And if we run with this theory, how is it impossible to think that it was for the love of a woman that Marco Polo shut himself off from the world for so long - a woman to whom he enjoyed recounting the imaginary travels he invented for her and the purely fictional countries he struggled to cross, braving a thousand deaths in his mind?

Extracted from ‘How to Talk About Places You've Never Been: On the Importance of Armchair Travel' by Pierre Bayard (Bloomsbury, £18.99), to be published on 19 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments