In pop culture, there are no bad police shootings

Hollywood has promoted the very myths that result in our being shocked when we see an officer shoot a fleeing person or fire into a parked car, as well as an inflated narrative of valour that generates a near-automatic presumption of the guilt of those killed by police

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

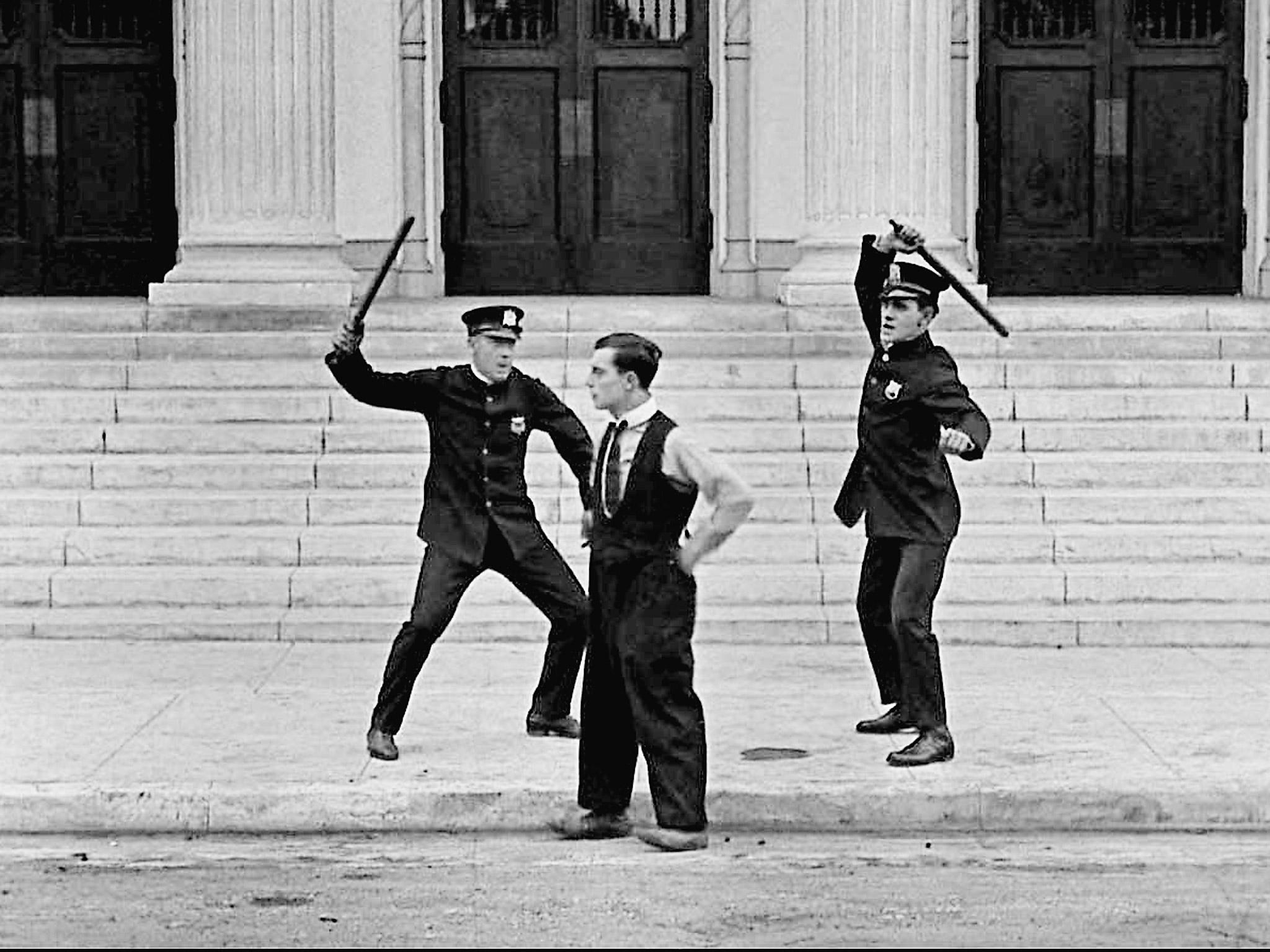

Your support makes all the difference.Buster Keaton’s 1922 short film Cops begins with a mistake. “The Great Stone Face”, as the actor was known, is driving a wagon when he wanders into the route of a Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) parade. If that isn’t enough to annoy the police commissioner, things get worse. Keaton’s character lights a cigarette on what he suddenly realises is a bomb fuse planted by an interloper, and then tosses the device away, frightening the policemen and wounding some. In the final moments of the film, the police find Keaton, and a mass of officers pulls him into a police station. The scene cuts out there, and the screen shows a grave marker with “The End” chiselled into the stone. Keaton’s porkpie hat hangs uneasily from the edge. The message is clear: Keaton’s character is dead, executed for another man’s crime.

Even by the standards of other contemporary silent films, including Keaton’s Convict 13, which includes an extended mock hanging, and Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, where mounted police charge at labour demonstrators and beat them with batons, Cops offers an exceptionally grim vision of police work. In the context of the next century, Cops becomes even more striking. Keaton was early in his decision to depict police killing a civilian in circumstances that are obviously, outrageously wrong. In the years to come, only a handful would do the same.

Just as the laws are structured so broadly that police officers are rarely charged or convicted when someone dies at their hands, American popular culture has spent decades telling audiences that there’s almost no such thing as a bad shooting by a police officer. This is not the first moment in which Americans have reacted with anger and horror to the killing of civilians by the police. But decade after decade, pop culture has continued to churn out stories that justify and even lionise officers who kill. These stories first turned shootings – and they are almost always shootings – into acts of last resort by noble policemen, and later into exciting executions of dangerous villains. Hollywood has promoted the very myths that result in our being shocked when we see an officer shoot a fleeing person or fire into a parked car, as well as an inflated narrative of valour that generates a near-automatic presumption of the guilt of those killed by police.

★★★

In the real world, two Supreme Court cases set national legal standards for officer-involved shootings. Tennessee v. Garner, decided in 1985, declared that officers couldn’t shoot fleeing suspects simply to stop them from escaping. Four years later, in Graham v. Connor, the court established a standard of “objectionable reasonableness” for police shootings: whether a reasonable cop in the same situation would have decided to open fire.

Yet for decades, pop culture has implicitly argued that fictional cops have been exceeding legal expectations when they shoot suspects, resisting even reasonable fears to act with great calm and precision. The result is a cultural narrative that simultaneously whitewashes the behaviour of police officers and sets a bar for competence and coolness under extreme pressure that real cops can’t possibly meet. Movies, television and novels have trained audiences to excuse almost any police shooting, including the deaths of children – until now, when the emergence and near-ubiquity of real-life videos have made the gap between fiction and reality undeniable.

Whether a shooting is legal is determined in part by an officer’s fear. But when the LAPD cleared scripts for television series such as Dragnet or Adam-12, “any shooting that was done on the shows was squeaky clean”, explained former detective sergeant Joseph Wambaugh, who worked briefly in the LAPD’s public information office, where the scripts were reviewed. “Any officer would have to be in total control.”

If this standard had nothing to do with how officers actually reacted after shooting someone, it was intended to bolster the audience’s confidence in police officers. In fact, officers on early cop shows such as Dragnet and Naked City were often presented as so decent that they questioned their own decisions to shoot and had to be convinced that they’d done the right thing. Often, the person doing the convincing was a parent or relative of the dead person.

The first time Joe Friday (Jack Webb), the archetypal stoic police officer, killed a person in the Dragnet episode “The Big Thief”, he was so distressed that his partner had to help him fill out his incident report. “I kind of wonder if there was another way,” Friday declared glumly, unconvinced that he was right to shoot even though the other man had a gun. Friday was ultimately reassured by the law itself, when the shooting was ruled a justifiable homicide.

Friday’s question hangs in the air, but it both casts and dispels doubt in a single sentence. If someone who cares as much as Joe Friday does couldn’t find a better solution when confronted with a dangerous criminal, then maybe one doesn’t exist. Friday’s concerns are themselves the proof that he would never do the wrong thing. Naked City, which premiered in 1958 as Dragnet was winding down and countered Dragnet’s narrow focus on crime with stories that exposed larger societal ills, embodied an even more agonized point of view about what happens when police pull the trigger.

The third episode began with the solemn warning that “to become the instrument of another man’s death … is to any sober-thinking person an act of shocking responsibility. It can haunt your conscience forever, torment a man beyond all reason, even when the cause is just. Even when there is no choice.”

In the show that followed, young Detective Jimmy Halloran (James Franciscus) killed a man for the first time, shooting an armed robber who was about to shoot him. Like Friday, Halloran received a verdict of justifiable homicide and wondered whether “maybe I could have done something else”. But where Dragnet ended on the verdict, in Naked City, Halloran spent the rest of the episode investigating the life of the man he killed.

Despite its liberal pretensions, Naked City reached a conclusion that would play out in pernicious form for decades to come. Though Halloran learned that his victim was popular at the local bar, generous with money and loved by his mother, he also discovered that the man abused and terrorised his wife. “Don’t feel sorry about Pete, Mr Halloran,” the widow said. “He wasn’t worth it.”

It might be regrettable for Halloran, with his finely tuned moral sensibility, that he had to kill a man. But the message in this episode of Naked City was undeniable: certain people are on an inevitable road to a violent end. These justifications showed up even in stories where the people who died were children. In Starsky & Hutch, Dave Starsky (Paul Michael Glaser) found himself at the centre of a racial maelstrom when he killed a black teenager, Lonnie Craig, who had shot a black policeman. Like Halloran, Starsky tried to learn more about the life he took and ultimately reached similar, if sadder, conclusions. Lonnie, it turned out, had escalated from running numbers to carrying out armed robberies.

“A mother knows what her son is. At least this mother knows,” Lonnie’s mother told Starsky, absolving him of the fear that he might have killed an innocent teen. By the end of the episode, Starsky was stopping by her house for smoothies and conversation. If the mother of a dead child could forgive the man who killed her son, the episode suggested, it would be churlish of us not to follow her example.

Indeed, as the crime wave that began in the 1960s endured, fictional police officers who expressed self-doubt after killing someone became increasingly rare. The archetype lingered for a time. In The Detective, Frank Sinatra’s principled cop resisted efforts to cover up a bad police shooting. And on Hawaii Five-O, Steve McGarrett (Jack Lord) warned protege Danno (James MacArthur): “It better tear your guts out every time you pull that gun, whether you use it or not.”

But even as Aaron Spelling pledged to members of his Mod Squad cast that their characters would never even carry guns, elsewhere the conviction hardened that some people simply needed to be killed, and any sense of regret or moral agony leached away. As the Seventies wore into the Eighties, officers emotionally debilitated by fatal shootings were depicted not as principled, but as weak.

The archetypal executioner was Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan, the embittered main character in the 1971 movie Dirty Harry. Harry began the movie deeply at odds with civilian authorities disgruntled by his quick trigger finger. “I don’t want any more trouble like you had last year in the Fillmore District. Understand? That’s my policy,” the mayor warned him. Harry responded: “Well, when an adult male is chasing a female with intent to commit rape, I shoot the bastard. That’s my policy.”

Rather than try to convince superiors that he’d done the right thing, Harry tossed his badge into the water and walked away. For him, at least, the law had become an obstacle to justice rather than the mechanism facilitating it

At the beginning of Dirty Harry, it’s unnerving to see Harry seeming to take cold pleasure in threatening a suspect with his gun. When a psychopath began stalking San Francisco, manipulating anti-police sentiments and Supreme Court rulings on suspects’ rights in order to continue his killing spree, Harry’s relationship with his department reached a breaking point. Harry first wounded the killer, then shot him to death when the man went for his own gun. Rather than try to convince superiors that he’d done the right thing, Harry tossed his badge into the water and walked away. For him, at least, the law had become an obstacle to justice rather than the mechanism facilitating it.

Later stories didn’t even attempt those philosophical questions, nor did they flatter the moral sensibilities of officers who showed an unwillingness to kill; instead, they suggested that such cops were fools. In the 1987 hit Lethal Weapon, Roger Murtaugh (Danny Glover) congratulated himself on shooting to disable a suspect, not kill him. But the man wasn’t sufficiently incapacitated, and when he rose, gun in hand, it was up to Murtaugh’s partner, Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) to finish the job.

Eight years later, in Bad Boys, Miami cop Marcus Burnett (Martin Lawrence) would indulge in similarly premature self-congratulation, leaving his partner Mike Lowrey (Will Smith) to shoot their suspect dead.

In 1988’s Die Hard, one of the defining movies in the cop canon, Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson), the patrolman who came to the aid of John McClane (Bruce Willis), explained that he had been exiled to a radio car for oversensitivity. “I shot a kid. He was 13 years old. It was dark. I couldn’t see him. He had a ray gun, looked real enough,” Powell explained. “You know, when you’re a rookie, they can teach you everything about being a cop except how to live with a mistake. Anyway, I just couldn’t bring myself to draw my gun on anybody again.”

The climactic, triumphant moment in Die Hard came when Powell regained the courage he needed to shoot the right people, taking down the surviving member of the crew that had commandeered Nakatomi Plaza.

There were exceptions to these celebrations of trigger-happy cops, of course. David Simon’s 1991 book Homicide and the television show adapted from it explored how policing was corrupted when departments shied away from taking responsibility for officer-involved shootings. And in 1983 on Hill Street Blues, Mike Perez (Tony Perez) shot a child playing with a toy gun, mistaking a shadow on a wall for a real weapon. Like Starsky before him, Perez received absolution from the child’s mother. Hill Street Blues suggested that Perez would punish himself worse than any court could: By the end of the episode, he had attempted suicide.

★★★

Though even the deaths of children were forgivable, there is one category of police shootings that pop culture through the decades has placed beyond the pale: incidents in which officers shot and killed other cops. And in a nifty bit of framing, pop culture tended to suggest that the very act of killing another officer expels a cop from the fraternity, stripping him or her of his identity as police officer. In the 1973 movie Serpico, the officers who tried to assassinate Frank Serpico (Al Pacino), who attempted to blow the whistle on departmental corruption, ultimately proved themselves less loyal to the values of the New York Police Department than Serpico himself.

In Insomnia, Pacino would reverse roles, playing a cop who shot his partner in the confusion of the Alaska fog. It first seemed like a tragic error, but later became proof that he was losing control of himself. And in FX’s drama The Shield, we first learned the true nature of Vic Mackey (Michael Chiklis) when he shot a young officer who had been assigned to Mackey’s strike team in order to investigate him.

That was bad, but the real horror of The Shield came in 2008. In the show’s final episodes, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who offered Mackey a job and immunity for testimony against his colleagues discovered that she has saddled herself with a cop killer. If a cop who killed other cops was bad, a cop who killed other cops and couldn’t be purged from the force is worse. He was a contagion, giving the lie to the idea that police departments can purify themselves. In the intervening years, The Shield vacillated between condemning Mackey and indulging in his dark allure. It would take another police show, set on another coast, to fully de-glamorise police shootings.

“The only police shootings we had were fucked up,” David Simon told me of the way The Wire approached gun use. Instead, The Wire defined its approach to guns with pitch-black humour and a keen attention to the bureaucratic processes surrounding guns. In one early scene, Detective Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West) drank beer by the railroad tracks with his best friend and partner, Bunk Moreland (Wendell Pierce), and listened to Moreland complain about being called home to dispatch a mouse from his wife’s closet. “I lit his ass up,” Moreland declared. “First shot killed my wife’s dress shoe. Got him with the second.” It was a perfect combination of mundanity and disproportionate response.

Later in that first season, Roland “Prez” Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost), who had already made a name for himself by shooting his own car, accidentally fired a shot inside the office. “You let one go, you got to write [a report],” McNulty told him. “You got to justify the use of deadly force.” “Against a plaster wall,” Detective Kima Greggs (Sonja Sohn) chimed in.

Over the next two seasons, Prez shed his flaky reputation by cracking the codes that drug dealers use on their pagers and showing a talent for complicated financial investigations. It seemed that his psychological shakiness was behind him when the inevitable happened: responding to a call for help in one of Baltimore’s confusing back alleys, Prez failed to identify himself before he shot and killed a black officer. That shot Prez fired into the office wall had, in a way, finally met its target; the consequences of his skittishness arrived in devastating, if belated, fashion.

“I’m not sure I was supposed to be police,” he said when the review board handed down its verdict on the shooting, finding him guilty of failing to identify himself as a police officer. The plot is a sharp break with the stories of decisive, disciplined shooters that populate much of cop culture.

★★★

It’s not just bad police shootings that are missing from much of pop culture, but also the truth of police officers’ reactions when they fire a fatal round. “In real life, I’ve seen guys just completely break into little pieces after shooting somebody,” Wambaugh reflected of his own time in the LAPD. “It’s a totally different proposition from the stoic, disciplined portrayal of a cop in a shooting on one of those television shows.”

Part of the problem is that Hollywood portrays police-involved shootings as a common occurrence for individual officers; in reality, they are rare. In 2014, the most recent year for which numbers are available, the 35, 000 officers of the NYPD discharged their weapons only 79 times. Of those incidents, 35 fell under the category of “intentional firearms discharges during adversarial conflict”. Another 18 happened when an officer shot an animal. When they do fire, it’s also hard for real cops to shoot with the same precision that their fictional counterparts do.

Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand), the heavily pregnant Midwestern cop at the centre of Joel and Ethan Coen’s pitch-black comedy Fargo, managed to keep her balance well enough to shoot to disable her quarry, even as he slipped and slid across a frozen lake. In Hot Fuzz, Edgar Wright’s savage satire of action cop movies, Nicholas Angel (Simon Pegg) took on an entire village’s worth of gun-toting preservationists without killing any of them. Whether he was precision-shooting a hanging basket of flowers onto one antagonist’s head or engaging in ferocious hand-to-hand combat in a miniature model of the town, Angel employed all sorts of creative techniques to ensure that he brought his targets in alive, notwithstanding that they had been murdering the town’s undesirables.

In this context, there’s something wistful about Paul Verhoeven’s dystopian 1987 action movie RoboCop. It’s a raw, often disturbing movie. But the prospect of an officer who has the programming that prevents him from ever killing an innocent person actually feels like an aspirational fantasy. Stories like these draw us directly to the contradictions in how both Hollywood and our police departments think about officers and guns. We want cops to draw their guns rarely, but to be outstanding shots when they do unholster their weapons. We want the police to feel the full weight of taking a life, and yet to pull the trigger in a state of perfect calm and conviction.

The way Dan Goor, the co-creator of cop sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine, has addressed these dilemmas is to try to avoid them. Keeping in mind that real officers rarely fire their guns, Goor and his writing staff try to keep his characters’ guns holstered as often as the imperatives of Hollywood storytelling will allow. Still, Goor told me in an interview, “sometimes you have to [pull a gun] because it’s a TV shorthand that everyone has come to accept.”

★★★

I’ve reached this point in pop culture history without saying very much about the people who find themselves on the wrong end of police officers’ guns, batons and fists. That’s not because the rosters of the dead, both fictional and real, are unimportant, but rather because pop culture rarely tells stories from their perspectives. And police stories face particular challenges in trying to humanise the people who die when cops pull the trigger. When police officers are the main characters in stories, and when those officers kill, the basic gravity of storytelling generally compels artists to sympathise with the cops, rather than with the people who end up dead. For stories that humanise people killed by the police, we have to look instead to fiction where police officers are secondary characters. Just as successive generations of cop stories are consistent in their presentation of police shootings as justified, characters in other kinds of fiction feel the same confusion and fear that Buster Keaton’s character did in Cops.

Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s 1989 chronicle of an alternately languid and tense summer day in Brooklyn, climaxes with the death of Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), choked by a police officer attempting to break up a riot. Tellingly, in Do the Right Thing, the normal polarity of a fictional police killing is reversed. The cop is essentially anonymous, while we’ve come to know Raheem’s love for Public Enemy and his loyalty as a friend over the course of the movie. As Raheem died, Lee focused closely on his straining face. And after Raheem’s death, the officers loaded his body into their squad car and drove away; whatever trauma the police might have felt was less important than the wreckage they left behind. The members of Raheem’s community, not the officers who killed him, were the people who would have to reconcile themselves to the realities of his life and death.

Ryan Coogler’s 2013 debut feature, Fruitvale Station, went even further, walking viewers through the closely observed last day in the life of Oscar Grant (Michael B Jordan) before he was shot and killed on a Bay Area Rapid Transit platform. By the time Oscar died, we knew more than his favourite song: we became acquainted with his sense of humour, his attempts to be a responsible partner and father, and his relationship with his mother. When the bullet that killed him arrived, Coogler didn’t give us a commonplace action set-piece. It was shocking and unusual; the look on Grant’s face when he was shot was uncomprehending.

Maybe that’s as it should be. In an attempt to grapple with the moral weight of police killings, Dragnet, Naked City and Starsky & Hutch suggested that such deaths were inevitable. In response to rising crime and to compete in an action-movie market that demanded escalating stakes, Dirty Harry, Lethal Weapon and Die Hard suggested that killing was necessary, even normal. Along the way, these stories obscured the truth Buster Keaton offered us in Cops. No matter how badly we want to be safe, no matter how heinous the offence, and no matter how clear a police officer’s justification, there’s no disguising the fundamental horror of taking a human life.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments