The Big Question: Does screening for breast cancer help or hinder treatment?

Why are we asking this now?

A report yesterday claimed that breast screening saves two women's lives for every one who receives unnecessary treatment.

It is the latest salvo in a long dispute about the benefits and risks of screening for breast cancer (and indeed screening for other cancers) and will be seen as a vindication of those who support screening. The report, by Professor Stephen Duffy, Cancer Research UK's expert in cancer screening at Queen Mary, University of London, and colleagues concluded that screening saved 5.7 lives per 1,000 women screened over 20 years, and caused just under half that number, 2.3 women per 1,000, to undergo unnecessary treatment.

How can screening for cancer be damaging?

Being told you have a life-threatening condition is no joke. The disease may be harmful, but so can the knowledge that you have it be. This is not widely understood by patients. There is an assumption that, if you have cancer, the sooner you know about it, the sooner you can do something about it and the better your chance of a cure. While this can be true, it is not always so. In some cases, the cancer detected in screening does not need treating, either because it resolves naturally or because it is very slow-growing (so you die of something else). In these cases, the only result of screening is that you spend more of your life living in the shadow of cancer, without living longer. You may be treated, and suffer pain and anxiety, to no avail.

How is a woman to make up her mind?

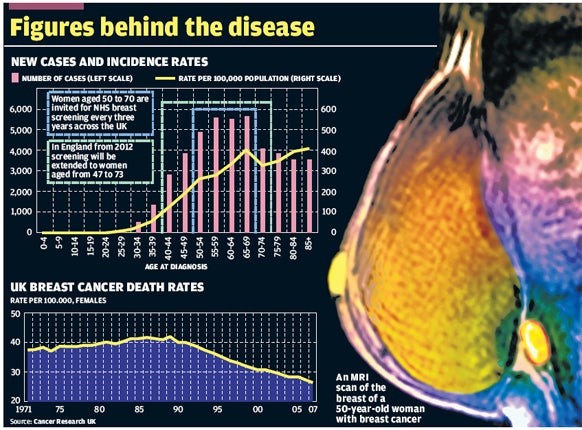

With difficulty. The national NHS breast screening programme was introduced in 1988 and women aged 50 to 70 are invited for screening every three years. The programme is being extended to include women aged 47 to 73 by 2012. The NHS Cancer Screening Service estimates that breast cancer screening saves 1,400 lives every year, one for every eight women diagnosed. Figures for 2006-07 show screening detected almost 13,500 cancers.

Isn't that good news?

It would be if there were no downside. But some of those women were either wrongly diagnosed with cancer, and later cleared, or diagnosed with a form of breast cancer that may not need treatment and resolve naturally. One sort, called ductal carcinoma in situ, is described by some specialists as pre-cancer on the basis that it often does not progress to cancer. There are other forms that also do not require treatment in all cases. But everyone who has cancer detected at screening is offered treatment.

How much of a problem is over-diagnosis?

That has been the subject of dispute ever since the breast screening programme began. A series of papers in the last year from Scandinavian researchers – who have a longer history of breast screening and a long history of scepticism about it – have suggested it is much higher than Prof Duffy found. One analysis, published in the British Medical Journal, concluded that for every woman saved, 10 underwent unnecessary treatment – which can include surgical removal of the breast (mastectomy) – and up to 500 had at least one false alarm, half of whom would have had a biopsy (removal of a sample of breast tissue).

Where does this leave women?

Gilbert Welch, a professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy in the US, said in an editorial published with the BMJ research: "The question is no longer whether, but how often, over-diagnosis occurs. Mammography [breast screening] is one of medicine's close calls – a delicate balance between benefits and harms. Mammography undoubtedly helps some women but hurts others. No right answer exists, instead it is a personal choice."

Isn't it better to be safe than sorry?

Some women take that view and opt to have treatment, even including mastectomy, if anything suspicious is found. They then have peace of mind. But it is a heavy price to pay if the "cancer" detected was of the kind that would have resolved naturally, without treatment.

What is happening with breast cancer?

Both good and bad. The good news is that deaths from the disease have fallen to a record low. After rising from 12,000 deaths a year in the early 1970s, to peak at 15,625 deaths in 1989, mortality has plummeted, bringing the number of women dying below 12,000. More than 75 per cent of women diagnosed with breast cancer survive more than five years today, compared with 50 per cent in the early 1970s. But while the death rate has fallen, the incidence of the disease has soared, doubling since 1971 to more than 45,000 cases a year. Breast cancer is now Britain's most common cancer, even though it principally affects only one sex (there are a few hundred male cases per year). Almost 40 years since statistics on the disease were first collected, and after the expenditure of billions of pounds on research and treatment, we have twice as many women being struck by the disease and almost the same number dying.

What about other forms of cancer screening?

The same problems apply. There is a risk of over-diagnosis and unnecessary treatment which has to be balanced against the clear benefit of detecting cancer early and treating it while there is the best chance of a cure. The NHS has screening programmes for cervical cancer and bowel cancer but has resisted pressure to screen for prostate cancer because the existing tests are considered not sufficiently accurate – ie carry too high a risk of over-diagnosis and unnecessary treatment.

Is age a factor in screening?

Always. Screening for bowel cancer, which is still being rolled out around the country, begins at 60. Bowel cancer is the second-biggest cause of cancer death (after lung cancer) so it is a very serious disease. About half of those who are diagnosed die but 90 per cent of cases can be treated successfully if caught early. Charities argue that screening should start at 50. Experts are resistant because 83 per cent of cases occur in the over-60s. In the case of cervical screening, demands for the starting age to be reduced from 25 to 20, after reality TV star Jade Goody's death from the disease last year, have been rejected for the same reason that there are too few cases and too high a risk of over-diagnosis.

Should breast screening continue?

In the mid-1980s, Britain's death rate from breast cancer was the highest in the world. Since then it has fallen faster and further than in comparable countries. The main reason is the recognition that the earlier cancer is diagnosed the easier it is to treat and that women treated by a breast cancer specialist (as opposed to a general surgeon) have a better chance of survival. Screening has played a part in ensuring that more women are diagnosed earlier. But some doctors argue that the money spent on breast screening – £40m a year – would save more lives if it were used to provide more treatment.

j.laurance@independent.co.uk

Should women get themselves screened for breast cancer?

Yes...

*Early detection and diagnosis of breast cancer provide the best chance of long-term survival

*The lives of about 1,400 women a year are saved according to the NHS screening service

*It is better to know than to not know, and to be safe than sorry

No...

*There is a risk of some forms of 'cancer' being over-diagnosed and then unnecessarily treated

*A positive result indicating cancer may cause needless alarm

*It is possible to have cancer and die with it, rather than from it

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks