Climate change fuels surge in wildfires sparking concern of ‘devastating consequences’ if left unchecked

Milder winters, and longer, drier springs and summers mean UK is likely to experience fire risk more akin to the Mediterranean

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The number of wildfires recorded in England and Wales so far this year has already surpassed the 2021 total, fuelling concern for what the future might hold if the climate crisis is left unchecked.

There were 243 wildfires from January to April, compared to 237 for the whole of last year, according to figures logged on the National Fire Chiefs Council National Resilience reporting tool, shared exclusively with The Independent.

Firefighters and wildfire experts warn the intensity and frequency of larger wild blazes have increased in recent years, likely due to a dangerous mix of climate change, a lack of land management, arson attacks and accidental fires.

“I am very fearful that a member of the public or a firefighter is going to get seriously hurt,” said Craig Hope, a wildfire tactical adviser at South Wales Fire and Rescue Service, who said more prevention work is needed, along with better training for firefighters who tackle the blazes before the problem got worse.

“For politicians and policymakers there is a window of opportunity which is now,” he said.

Paul Hedley, the lead on wildfires for the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) who is also chief fire officer for Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service, said when he joined the service in 1987 there were examples of large fires but they were infrequent.

“You used to get really significant seasons for wildfire, and then you’d get a period of four or five years where everything would drop down,” he said. “What we’re starting to see is annual increases, where we’re getting more of these fires.”

Milder winters, and longer, drier springs and summers mean wildfire-supportive conditions are becoming more prevalent, Mr Hadley said.

And while the “fire season” was once considered to be from late March to the end of September, last year the first was recorded on 11 February and the last on 2 December.

“We’re seeing fires more regularly through the whole course of the year,” he added. “Climate change is making it easier for those fires to occur.”

Mr Hedley’s analysis is backed by Thomas Smith, an associate professor in environmental geography at London School of Economic and Political Science, who said climate change is increasing the frequency of heatwaves and dry spells in the UK, which helps set the conditions for wildfires.

“Without rapid mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, we are committing ourselves to a future when the UK will experience fire risk more akin to the Mediterranean region, with the potential for extreme fire risk every year,” he told The Independent. “The consequences of this could be devastating for our unique ecosystems and crucial forestry carbon stores which are themselves an important climate change mitigation strategy.”

The NFCC reporting tool only records significant wildfires that meet one or more of its criteria, which includes that it impacts an area bigger than one hectare, has sustained flame lengths of more than 1.5 metres or presents a serious threat to life, environment, property and infrastructure.

It was introduced in 2018, and while the data for 2018 and 2019 is considered patchy, the past three years have seen annual increases in the number of blazes, rising from 146 in England and Wales in 2020, 237 in 2021 and 243 by the end of April this year.

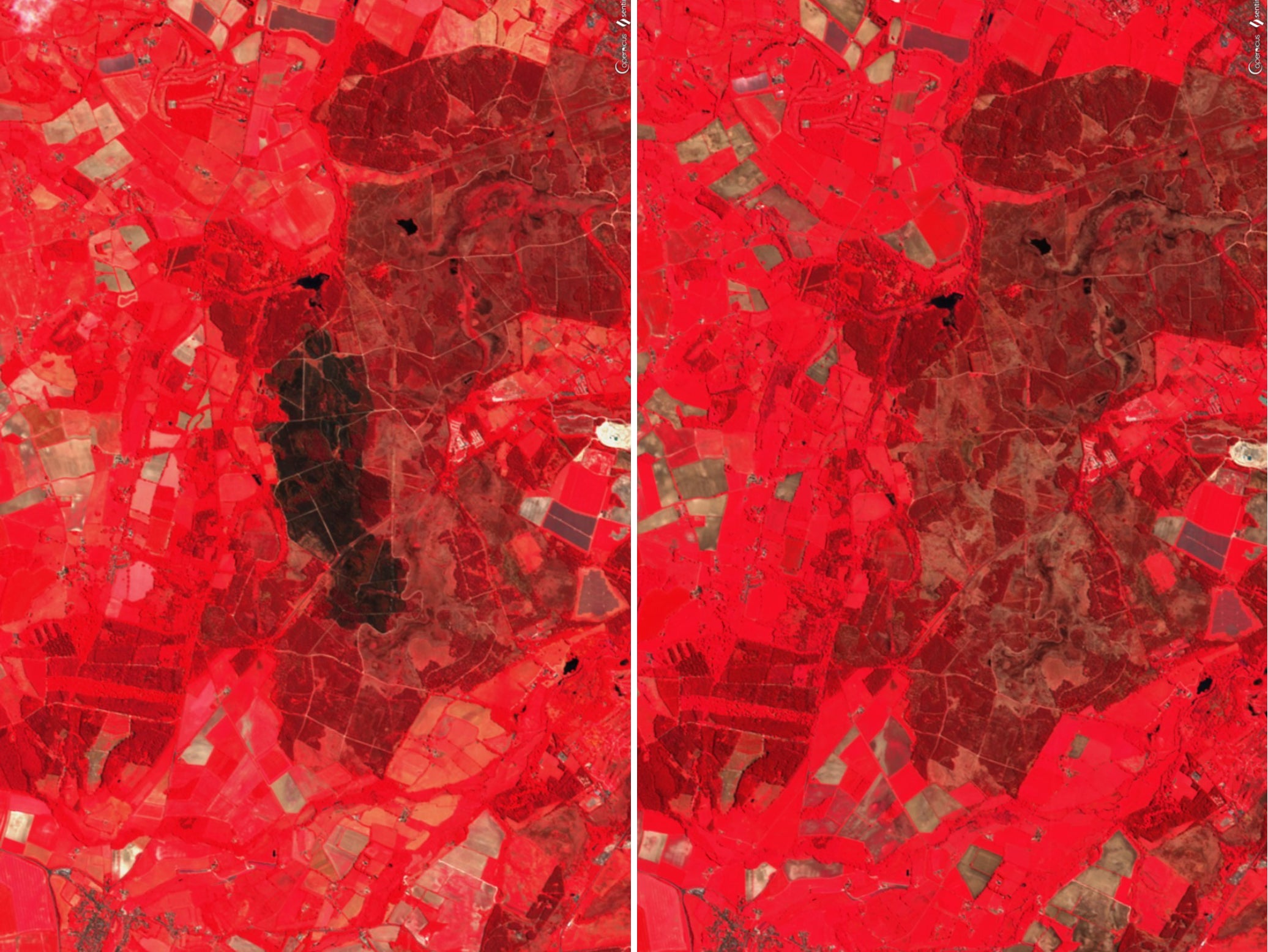

The increase in their number and severity is also reflected in other data. Dr Smith has found that the number of fires in the UK has increased year on year since 2014, with a marked increase from 2018 onwards, according to satellite data from the European Forest Fire Information Service.

The scale of the burnt area has also increased, indicating the fires are becoming more intense. He cautioned that the satellite data did not go back far enough to establish a long-term trend but said the increase in the areas affected in the past four years was clear.

Beyond climate change, firefighters and Dr Smith said changes in the way land and vegetation – or fuel – on the ground is managed may also have played a part in their frequency and spread.

“We’re seeing an increase in the amount of fuel out there,” said Robert Stacey, wildfire team leader at Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service. “If we’ve got more fuel and we get a fire into it it becomes a more difficult fire to extinguish and suppress.”

In Northumberland, for example, planned burning of heather in the uplands has declined, and there is now a blanket ban on burning deep peat, he said. There has also been a decline in farming, meaning animal grazing on the land has declined and vegetation is allowed to grow and can pose a risk. Such land may also be at a higher risk of catching light if not properly managed, as the vegetation can turn into a fuel during a dry spell, firefighters warned.

It is a similar picture in south Wales, where sheep have been moved from the uplands into paddocks lower down, increasing the risk of upland fires where the grasses are very fine and easily catch ablaze, according to Mr Hope.

The good news is that land management is an area where the community can have an impact, by introducing fire breaks in the vegetation, planting fuels that are more fire resistant and reintroducing grazing, the firefighters said.

“We can’t control the arsonists, and we have tried, we can’t control the weather, and we’re seeing that, especially now, but we can control the vegetation,” Mr Hope said, explaining that south Wales also has a particular problem with deliberately lit fires.

Wildfires can affect any land type with vegetation, whether agricultural standing crops, forestry, heath or scrubland, firefighters said. They tend to occur more frequently in rural areas, but can threaten settlements and break out in urban areas. In 2018, for example, a huge blaze tore through a grassy area in Wanstead Flats, in east London.

Andy Elliott, a wildfire tactical adviser at Dorset and Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Service, fought the Canford Heath fire in Poole, Dorset, last month that resulted in homes being evacuated.

“No properties were damaged or lost,” he said. “But if you’re a resident there, understandably they’re going to be very concerned and scared by that.”

Mr Elliott, who has been a firefighter since 1983, said he had also noticed the frequency of high-intensity wildfires had increased.

“This has to be linked to climate change,” he said. “And it’s set to get worse.”

Mr Elliott said the fire service recognised the problem and was increasing the quantity and quality of wildfire training, which started with the introduction of national wildfire tactical advisers in 2018. But he agreed more could be done to better prepare firefighters across the UK.

He said he was alarmed, for example, to see photographs of firefighters fighting wildfires in T-shirts because they’ve stripped off their heavy gear to climb remote hills where the fires often are. In south Wales, the service has developed lightweight firefighting kit specifically for fighting wildfires for that very reason, he said.

“It’s no longer an anomaly, these fires are here to stay,” he said.

Mr Hope said dealing with wildfires could also slow down the service’s ability to respond to other incidents.

Mr Hedley said wildfires were resource-intensive and can last days or even weeks, meaning other units may have to be called upon to help. That happened at the Saddleworth Moor fire, near Manchester, in 2018, where it took more than three weeks to extinguish the blaze.

Mr Hedley said the country had developed a group of around 50 wildfire tactical advisers from services across the UK, who can support the incident command team in their tactical and strategic plan for tackling the wildfire.

England has also recently published a wildfire framework to help firefighters work with the government and local communities to better mitigate risk, while their counterparts in Scotland and Wales were working on their own.

“We’ve come an awful long way in 10 or 11 years,” he said. “We just need to keep this momentum going.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments