Scientists are eavesdropping on whales -- and it could save their lives

‘This system could become like satellites in the ocean’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists for the first time have developed a way to eavesdrop on the conversations of whales across vast expanses of ocean.

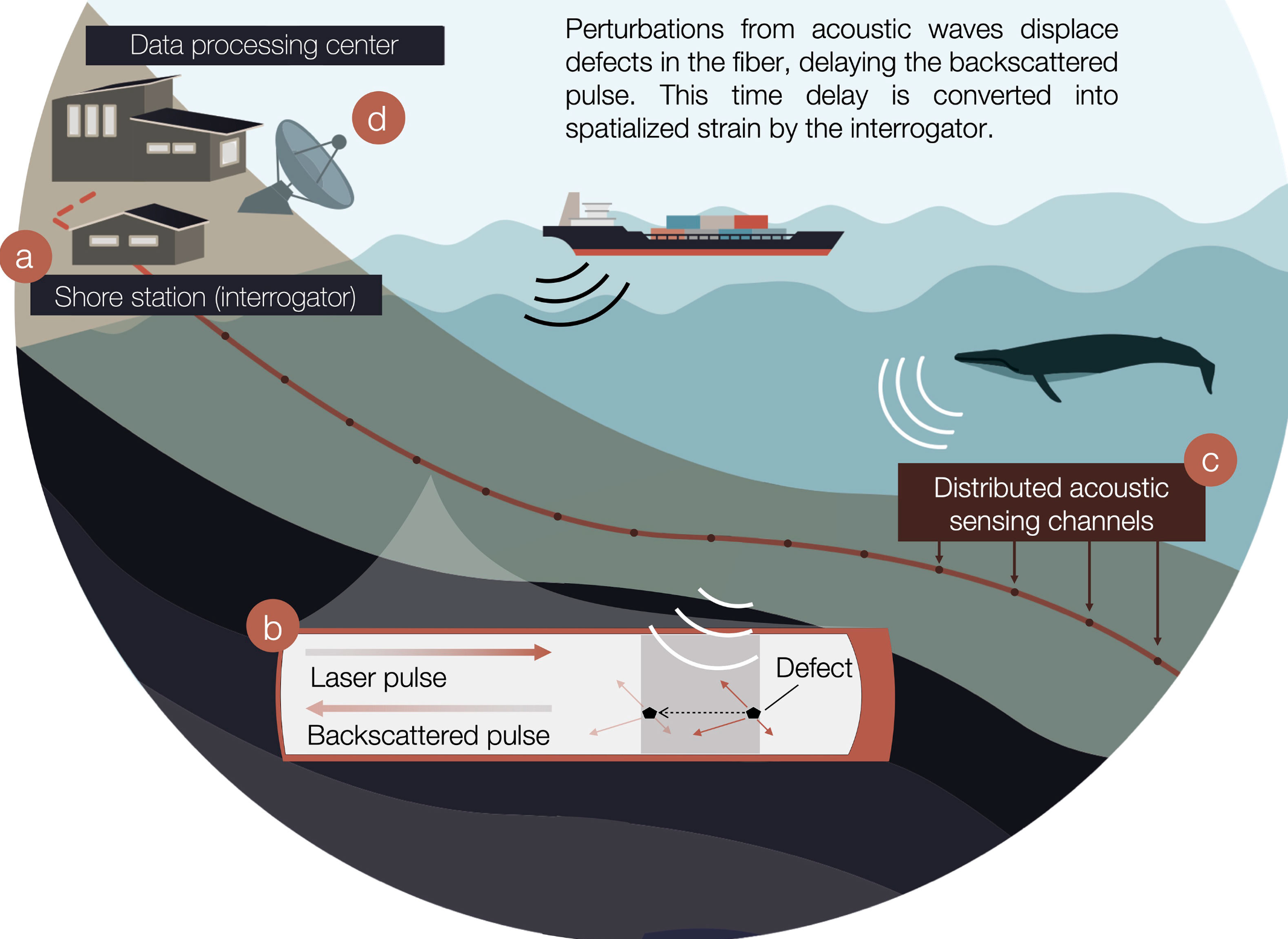

So-called Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) uses an “interrogator” instrument to tap into existing, underwater fibre optic cables, and converts unused fibres into a long line of virtual hydrophones - essentially, underwater microphones.

The research project was carried out in Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago between Norway and the North Pole, where baleen whales, like blue whales, forage in the summer months.

Whales are valuable indicators of ocean health, and following their underwater calls to each other is the best way to study the elusive large mammals.

For 40 days in summer 2020, researchers listened along 75 miles (120km) of cable buried beneath the seabed between the archipelago’s main town, Longyearbyen, and Ny-Ålesund, a research settlement.

Whale calls are normally monitored using satellite tracking, aerial surveys, sightings and individual hydrophones. However, studying a limited ocean area can make it challenging to understand whales’ migratory routes, for instance.

The difference with DAS is that it not only allows researchers to detect whale calls, but piggybacking on to a widespread fibre network allows scientists to locate where whales are in both space and time.

Dr Léa Bouffaut, a researcher at the K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics at Cornell University, described the significance of the innovation for the field of marine bioacoustics.

“Deploying hydrophones is extremely expensive. But fibre optic cables are all around the world, and are accessible,” she said in a statement on the study, published this week in journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

“This could be much like how satellite imagery coverage of the Earth has allowed scientists from many different fields to do many different types of studies of the Earth. To me, this system could become like satellites in the ocean.”

Researchers can also use DAS to “hear” other sounds carried through the water, from large tropical storms and earthquakes to ships passing by, said Martin Landrø, a geophysicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, who co-authored the paper.

The scientists underlined the importance of the system in the Arctic region -- where the climate crisis is causing warming three times as fast as the global average.

Last month, a severe heatwave in Europe led to record-breaking temperatures including in the Arctic Circle where temperatures in the far north of Norway reached an unprecedented 32 degrees Celsius.

Dr Bouffaut noted that while blue whales aren’t currently seen in the Arctic year round, this could change as ice sheets further disintegrate. Less ice cover also opens the possibility of more shipping, fishing and tourism in the region.

More vessels increases the risk of ship strikes of whales but DAS could play a role in combatting this danger.

If DAS data could be analysed in real time, the information could be relayed to ships travelling in waters where whales are feeding or socializing, and also help protect them.

Hannah Joy Kriesell, one of the paper’s co-authors, said: “[If] we have a means to inform ships about the location of whales in real time, we could stop or at least reduce the risk for ship strikes.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments