Giant ice sheet that could flood London is more resilient than previously thought

However the current rate of sea level rise is expected to cause serious problems for major coastal cities over the next century – and Pacific islands are already disappearing beneath the waves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The vast West Antarctic ice sheet – which contains enough water to raise sea levels by up to nine metres – does not have appear to have suddenly collapsed over a few decades the last time the planet was warmer than it is today, according to new research.

There is concern that once the temperature hits a certain point, ice sheets will disappear increasingly quickly and then disintigrate.

The Greenland ice sheet, for example, lost a trillion tonnes of ice between 2011 and 2014, compared to nine trillion tonnes in the past 100 years.

Researchers at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have been trying to work out what happened to the much bigger West Antarctic ice sheet during a natural warm period some 128,000 years ago.

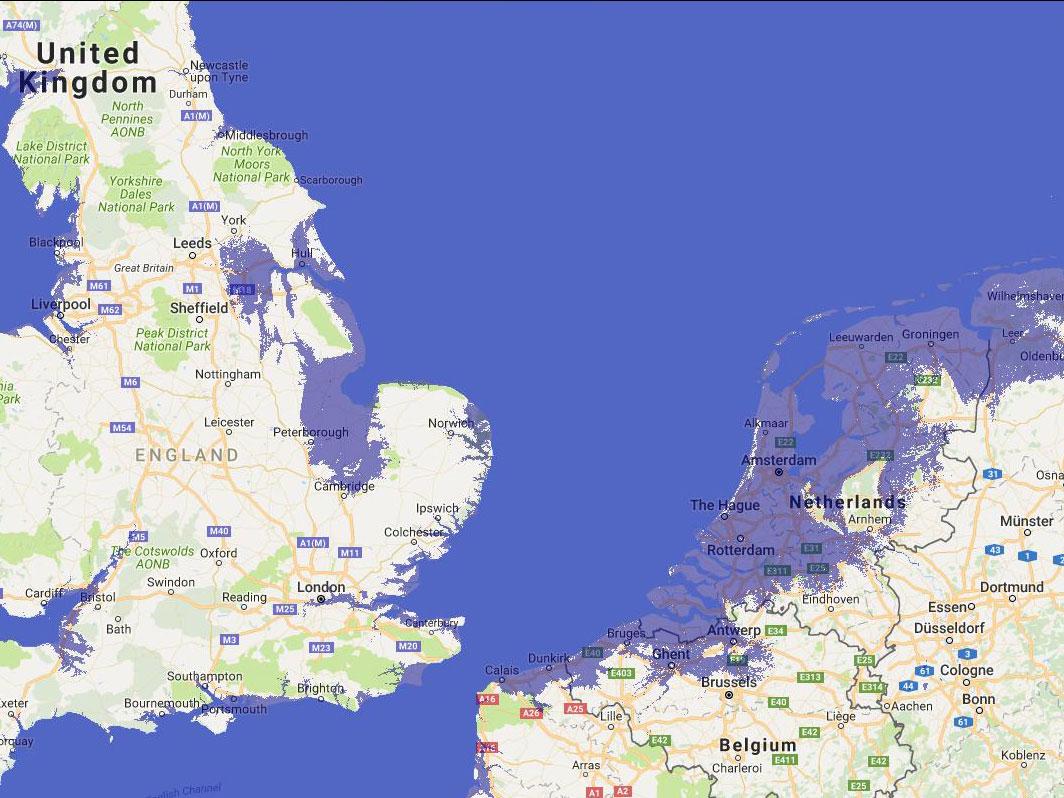

The interactive map below, developed using Nasa information by Alex Tingle of firetree.net, shows the effect of different degrees of sea level rise. At nine metres, vast areas of Yorkshire are submerged, the Wash expands dramatically and much of central London is underwater, while the Netherlands virtually disappears:

About 128,000 years ago, the world was hot enough to allow hippopotamuses to wallow in the Thames Valley.

Dr Louise Sime, a palaeoclimate modeller at the BAS, told The Independent that ice core samples suggested humans might have more time to come to terms with major sea level rise than some had feared.

“We think possibly the West Antarctic ice sheet doesn’t sort of collapse instantly over a very short period – and that’s been a worry,” she said.

“But it certainly may be susceptible to continuous melt over a longer time period.”

She said their results suggested the ice sheet had not melted within about 50 to 200 years – a ‘sudden’ change in these terms. “It probably took longer than that,” she said.

Dr Sime, co-author of a paper in the journal Nature Communications, said this was “potentially” good news, but added there was also some bad news.

“We have found out that sea ice is susceptible to huge losses and that has massive implications in terms of … life under the sea ice,” she said.

“We found out from this [study], that the sea ice is probably responding more quickly than the land ice.”

The sea ice around Antarctica shrank by about 65 per cent in winter during this natural warm period, they found.

While melting sea ice does not raise sea levels, it does increase the pace of global warming as white ice has a cooling effect, reflecting more sunlight back from the Earth’s surface than dark water.

The current rate of sea level rise is already more than enough to cause significant problems for low-lying Pacific islands, which have started to disappear.

Coastal cities like New York and Shanghai are also expected to see more severe floods over the next century with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicting sea levels are “likely” to rise between 26 and 82cm by 2100.

The broader lesson from 128,000 years ago is somewhat concerning. The temperature was higher than today even though the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere reached just 300 parts per million (ppm), compared to 400ppm today.

“The climate [today] hasn’t had time to respond fully to the CO2 we’ve put into the atmosphere,” Dr Sime said.

“We are now heading for a time that will be almost certainly warmer than the last interglacial. It’s just we haven’t got there yet.

“It’s really interesting to look at the past because the climate had long enough to adjust to higher levels of CO2.”

Dr Sime said she and others in the US were now planning to do more research to try to work out how long it took the Western Antarctic ice sheet to melt.

She stressed that the past was only an indication of what might happen in the future, not what would certainly happen.

Professor David Vaughan, the BAS’s director of science, who works on trying to predict what the planet’s future climate will be like, said the melting of ice sheets was an increasing threat.

“We have sea level rise which is higher than it has been historically. All of our projections suggest sea level rise will continue to accelerate through the next few decades. The question is really how much will it accelerate by,” he said.

“We will begin to have real, serious issues with maintaining the security of coast cities long before we get to nine metres.

“If you are talking about how we adapt to sea level rise, the first metre is really important.”

Professor Vaughan said researchers like Dr Sime were trying to work out what had happened in “almost a blink of an eye” in the Earth's history.

“There’s a huge difference whether the collapse occurred over 100, 200, 500 or indeed 1,000 years,” he said.

“We have to get down to that detail if we are hoping to use it to inform our projections.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments