Two-headed deer discovered in forest described as 'amazing' by scientists

'We can’t even estimate the rarity of this. Of the tens of millions of fawns born annually in the US, there are probably abnormalities happening in the wild we don’t even know about'

An “extremely rare” two-headed deer has been discovered by a mushroom hunter in a forest by a Minnesota.

The conjoined twin fawns appeared to have been stillborn, but they are the first ones known to have been carried to term and delivered by their mother.

After discovering the specimen while out foraging near the Mississippi River, the mushroom hunter delivered it to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, where Dr Gino D’Angelo was working at the time.

Fascinated by the unusual creature, the deer ecologist froze it until he was able to examine it in greater detail and investigate its anatomy.

“It’s amazing and extremely rare,” said Dr D’Angelo, who is now based at the University of Georgia. “We can’t even estimate the rarity of this. Of the tens of millions of fawns born annually in the US, there are probably abnormalities happening in the wild we don’t even know about.”

Together with his university colleagues, Dr D’Angelo carried out a full examination of the conjoined twins, and published the results in the journal American Midland Naturalist.

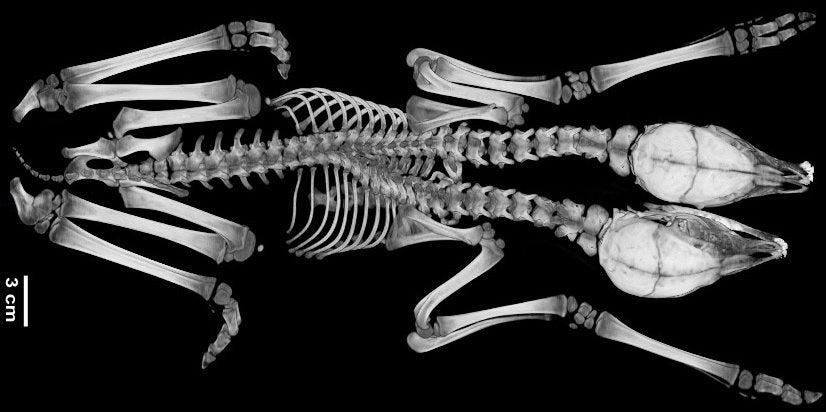

They dissected the fawns, but only after conducting CT and MRI scans of their shared body to understand the nature of their condition.

While the stillborn creatures had separate necks and heads, their spines were fused together so they shared a body – which was covered in “almost perfect” spot patterns running up their necks, according to Dr D’Angelo.

Their dissection showed that inside the deer had a shared liver, but separate spleens and gastrointestinal tracts, as well as hearts that were split but contained within a single pericardial sac.

Lab tests performed on the young deer’s lungs, however, showed that they had never breathed air and therefore must have been delivered stillborn.

“Their anatomy indicates the fawns would never have been viable,” explained Dr D’Angelo. “Yet, they were found groomed and in a natural position, suggesting that the doe tried to care for them after delivery. The maternal instinct is very strong.”

As part of their study, the scientists combed through the scientific literature dating back to 1671, and found only 19 confirmed cases of conjoined twins occurring in wild animals.

Previous cases had been confirmed in white-tailed deer – the species to which the Minnesota fawns belonged – but only in undelivered foetuses.

Conjoined twins occur in the human population at a rate of between one in 50,000 to one in 100,000 births, but the process that leads to the condition – in both humans and animals – is unknown.

“Even in humans we don’t know,” said Dr D’Angelo. “We think it’s an unnatural splitting of cells during early embryo development.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks