How the disturbing case of a TV weatherman shows the reality of reporting on the climate crisis

As the climate crisis grows, meteorologists, scientists and journalists alike are increasingly reporting on its impact on everyday life. But its not without risks, reports senior climate correspondent Louise Boyle

Chris Gloninger was at the barber’s shop when the death threat arrived.

After 17 years in television, the chief meteorologist for KCCI in Des Moines, Iowa, had grown a thick skin. But this was different.

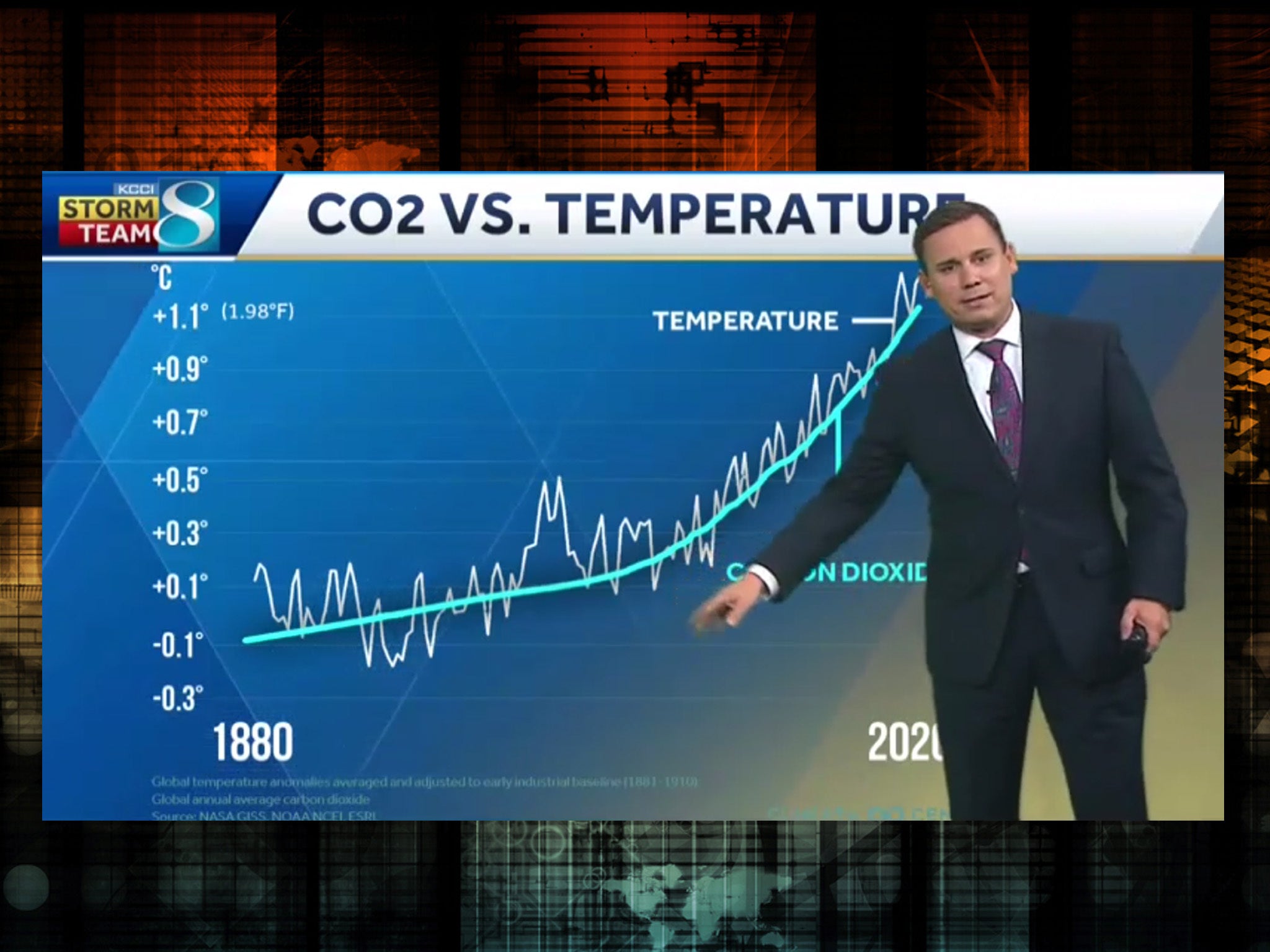

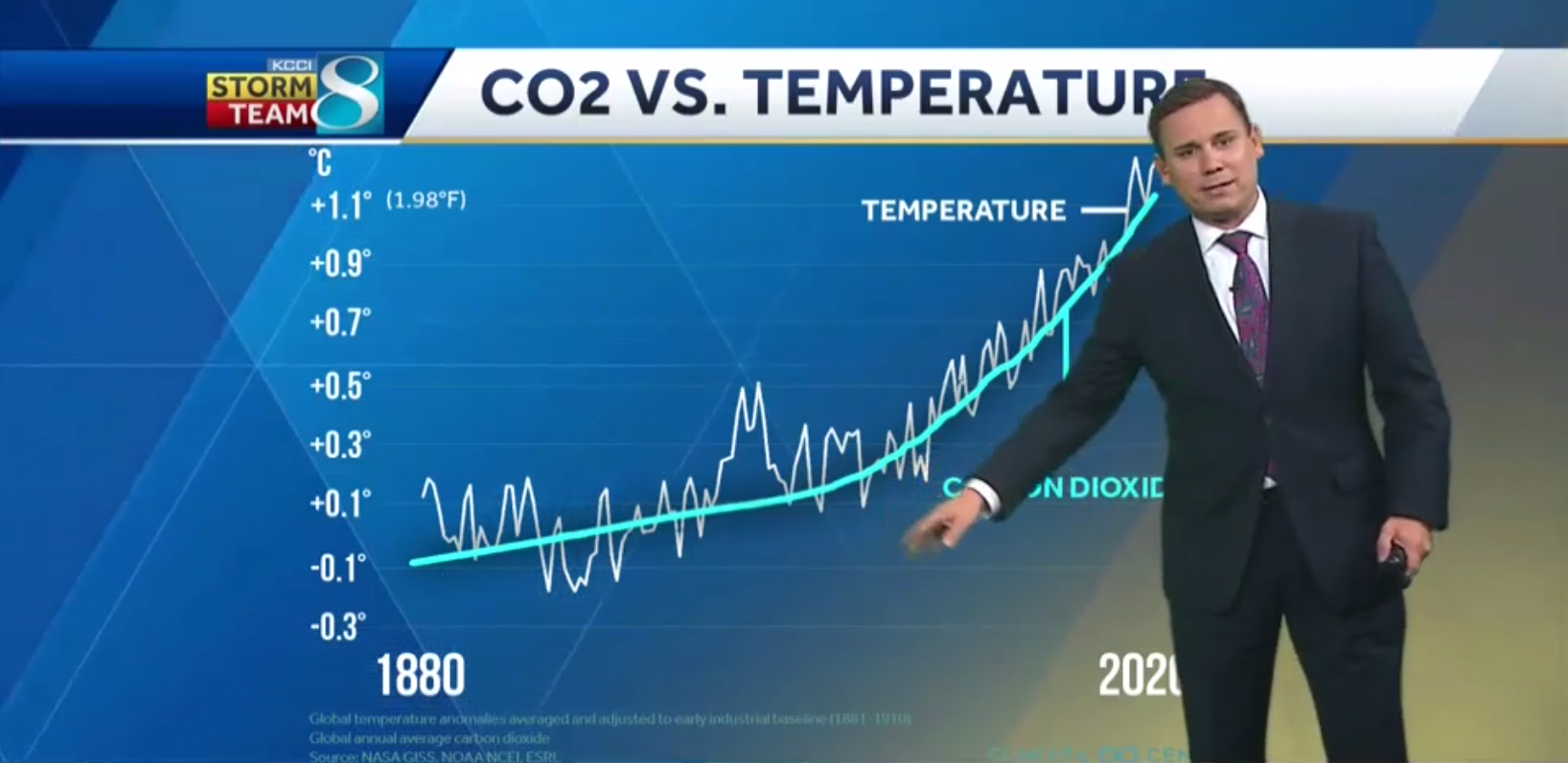

The emails started in June and were filled with anger over Gloninger’s weather forecasts. The forecasts routinely incorporated facts on climate change, a practice that he hoped would help viewers connect the dots between the global threat of a hotter planet and more extreme heatwaves, drought, and flash flooding at the local level.

“I think you can turn people off if you’re hitting them over the head with [climate change],” Gloninger told The Independent last month. “I don’t grasp at straws. I try to find connections that are meaningful and have an impact on viewers.”

The first email accused him of “liberal conspiracy theory on the weather”, adding that “climate changes every day, always has, always will, your [sic] pushing nothing but a Biden hoax, go back to where you came from”.

Gloninger, who grew up in Sag Harbor, New York, replied: “I’m sorry, it’s not politics, it’s science, and it’s supported by the vast majority of climate and atmospheric scientists. Thank you for watching.”

A few days later, another email dropped into his inbox.

“What’s your address, we conservative Iowans would like to give you an Iowan welcome you will never forget, kinda like the libtards gave JUDGE KAVANAUGH!!!!!!!” the message raged. The threat appeared to reference the news that a man had been charged with attempted murder after going to Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s home with a gun, knife, hammer, zip ties and other weapons.

“I was getting my hair cut and the email popped up and I just got this sinking feeling,” Gloninger said. “My wife was home, I was away, and I thought, I have to get home. I decided to call the police because it was more than just a mean email, it was a direct threat. Then it turned into an obsession.”

Gloninger became interested in weather as a child after Hurricane Bob hit his hometown in 1991, going on to graduate in meteorology from Plymouth State University and become a certified broadcast meteorologist with the American Meteorological Society.

Before landing the chief role in Des Moines, Gloninger worked at TV stations in Wisconsin, Michigan and Massachusetts. At NBC10 in Boston, he started the first weekly series on climate change, and reported on hurricanes, EF4 tornadoes, major flooding and ice floes.

Still, the email harrassment left him shaken, he said, fearing for his safety and his wife who was home alone when he worked late shifts at the TV station.

“I’ve never had mental health issues before,” Gloninger said. “It’s scary because there was a time, and there are still times, that I’m not okay after it.”

Following the death threat, KCCI’s parent company, Hearst, paid for the Gloningers to stay in a hotel while a security system was installed at their home. Security was also bolstered at the TV station, and at his public events.

“I’m blessed from that standpoint in this industry, especially [because] we don’t get that compassion as much anymore,” Gloninger said.

The harrassing emails continued for weeks. “I don’t watch your worthless weather forecast because your [sic] an idiot but someone else texted me and said you are still an idiot, go the hell back where you came from D********!!!” one read.

On 15 July, an email referred to Dr Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases who has led the US Covid-19 response. It told Gloninger to “go east and drown from the ice cap melting you dumbf***!!!!!!!”

Somewhat to his surprise, Gloninger said, police in Des Moines took the death threat and the harassment seriously. The digital crime detective took charge of the case and subpoenaed Google for phone data.

Danny H Hancock, 63, of Lenox, Iowa, was later fined $150 for sending the emails.

Gloninger’s experience appears to have been rare among colleagues. “When I connected with other meteorologists doing similar work, no one has ever experienced anything that dramatic,” Gloninger said.

Climate Central, a nonprofit which assists meteorologists with research and provides visual tools like graphics and maps, reported that the vast majority of meteorologists who have integrated climate science into their weathercasts have received less pushback than expected - even in very conservative areas.

However Gloninger’s experience also underlines a rise in online harrassment more broadly of those who talk and write about the climate crisis. The issue has become so dizzyingly politicized that even speaking the words can trigger a backlash.

“If you hear that your colleagues are getting harassed for putting information on social media or in media outlets, that has to have some sort of chilling effect on scientists,” Dr Jacob Carter, research director for the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told The Independent.

Overall, one-third of US-based journalists report being harassed on social media, according to polling by the Pew Research Center, with threats of physical harm the most common.

Journalists’ gender, race, and/or sexual orientation play a role in how much harrassment they experience. A quarter of both Black and Asian journalists (27 per cent) say they have experienced threats or harassment based on race or ethnicity, as do 20 per cent of Hispanic journalists, according to Pew. About one-in-six journalists who are women (16 per cent) say they have been sexually harassed by someone outside their organization, versus 3 per cent of men.

Science reporters, including those who write climate change, also appear to attract particular ire, according to a survey from journalism professors at George Washington University.

Joan Meiners, a journalist with the Arizona Republic, referenced the data in a recent article about the hatemail she has been sent on her climate reporting. Her interviews with colleagues around the country discovered many similar experiences.

For climate scientists, academics, and activists, some of whom have spent decades warning about oncoming devastating impacts even while the media was slow to catch up, speaking out has not been without risks. More than 1,700 people around the world have been killed for defending the environment in the past decade, a recent Global Witness report revealed.

Few scientists understand the threat better than Dr Michael Mann, a presidential distinguished professor of earth and environmental science, and director at the Penn Center for Science Sustainability and the Media, who regularly appears on TV to talk about climate change and has written dozens of articles. Such is his public profile that last year he was name-checked by Leonardo DiCaprio as his inspiration for the scientist he played in the movie, Don’t Look Up.

In the late Nineties, Dr Mann became the target of a vicious hate campaign after his research discovered that the sharp uptick in global temperatures over the past 150 years was unprecedented in at least 1,000 years and coincided to when humans began burning fossil fuels with abandon. More than 99.9 per cent of peer-reviewed scientific papers now show that climate change is mainly caused by humans.

In the wake of his study, Dr Mann’s emails were stolen and manipulated. He received thousands of abusive emails and death threats, and an envelope of powder was sent to his home, triggering an FBI response (it turned out to be corn starch). Ken Cuccinelli, a former Republican attorney general, called for his academic credentials to be removed. (Dr Mann later wrote a book about his experiences).

“I considered retreating into the lab, shunning the attention,” Dr Mann told The Independent, in an email this week. “But it just wasn’t in my constitution. I was always a fighter. I would fight back against bullies twice my size in grade school, because it was the right thing to do.

“And the fossil fuel industry and their henchmen—they’re the biggest bully on the planet. I knew I had to fight back, because the stakes were too great. It was just about defending my name and my research. It was about the greatest battle we face as a civilization. I feel privileged to have ultimately had an opportunity to participate in the effort to inform the public and policymakers about this defining challenge.”

He concluded: “You fight the good fight. Because it’s the right thing to do.”

While social networks and conservative media have played a sizeable role, the arteries of climate misinformation flow from the fossil fuel industry, which has known for nearly half a century that greenhouse gas emissions from oil, gas and coal use are heating the planet.

Fossil fuel companies have denied any campaign to mislead Americans, despite a publicly-available wealth of documents and statements to the contrary. The industry’s long-running misinformation campaign was the subject of Congressional investigation last year and has led to at least 20 lawsuits filed by US cities and states.

The deceptive tactics have taken a toll on the US public’s understanding of the climate crisis -- even as more communities face extreme heatwaves, droughts, wildfires and hurricanes.

While there is growing concern among Americans about the climate crisis overall, data shows, the political divide has deepened in the last 20 years.

Gallup polling in 2021 found that 32 per cent of Republicans attribute the rise in Earth’s temperatures over the past century to human activity, a drop from 52 per cent in the early 2000s. The percentage of Democrats who say humans have caused climate change has risen from 68 to 88 per cent over the same period.

It’s that divide that Gloninger said factored into his decision to take a chief meteorologist job in conservative-leaning Iowa, where talking about climate change could have deeper impact than “preaching to the choir” in more liberal Boston.

Climate change is personal, he pointed out, no matter where you’re from. Where Gloninger grew up on eastern Long Island, there was once a booming commercial fishing industry. As the ocean has warmed, that industry moved up to Maine and is shifting further north still, to Nova Scotia.

His hometown of Sag Harbor transformed into a weekend destination for well-heeled New Yorkers.

“It survived but in other parts of the country, they don’t always have that luxury,” he said. “I think people need to understand that [climate change] is not a future problem, that we’re starting to see these changes, with agriculture in Iowa, for example. These things make it real to people. How does it affect them? Why should they care?”

Gloninger debated at length with his wife on whether to speak publicly about the harrassment and death threat, and still worries about retaliation.

“I was so torn because what they’re doing the media and to science is scary and on the verge of being dangerous,” he said. “But I fear that if you let it go, that emboldens a certain part of the population that think it’s okay to be filled with hate, anger, and think that threats are fine to make.

“There’s been a tide change in the coverage of climate change, it’s becoming more mainstream but we’re still getting pushback. If people don’t realize that, then they’re not getting the accurate picture of climate communications.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments