The rise of the female cyclist: From the medal-winning track-speedsters to school-run mums

Sexism, apathy, injury, death… From city commuters to elite professionals, women in the saddle have had it too tough for too long. Finally, female cycling is about to step up a gear

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A year ago, Peter Sagan, a jockish Slovakian road racer, pinched the bottom of a young podium girl as she kissed the winner of the Tour of Flanders. As a scandal, it was minor by cycling standards, but it symbolised a major issue. The cyclist, who had finished second in the Belgian classic, apologised, but his actions and their fall-out had already said something more about a sport in which women have often been valued for their bearing in tight dresses. Because what few fans gleaned in the coverage of the pinch was that, on the same day, the brilliant Dutch cyclist Marianne Vos won the women's version of the race. Typically, it had not been televised.

It was sad, the cycling columnist Jane Aubrey wrote afterwards, that, "Instead of celebrating one of the most prolific athletes in the sport… we were again left to consider ways in which cycling sets women back and an industry that perpetuates a misogynistic attitude."

But wheels of change are finally turning in what should be a breakthrough year in cycling. In May, Vos will lead the world's best riders in the inaugural Women's Tour of Britain. More symbolically, after a campaign led by Vos and Emma Pooley, the British Olympian and former world champion, women will no longer be reduced to podium decoration at the Tour de France: they'll be lining up along a start line, too.

"Fifty years ago, they said that women couldn't run long distances," says 31-year-old Pooley. "Kathrine Switzer jumped into the Boston Marathon [in 1967] to prove them wrong. Today, people still say women can't ride the Tour de France, but there's no question that it's doable. And if they can [have equality] at Wimbledon and in marathons, why not at the most high-profile race there is?"

The women's race, called La Course by Le Tour de France, will be staged in Paris on the morning of the last stage of the men's event, crossing the same finish line on the Champs-Élysées. It is a pedal stroke in the right direction that follows earlier, failed attempts to stage a women's race that could be the Tour's equal. And it arrives at a time of progress in every area of cycling. From the velodrome and country lanes on a Sunday morning to the daily commute and school run, women are fast closing the gap in a male-dominated world. And they do so in defiance of the greater risk they face, particularly in our cities, and an establishment that has until now neglected them.

To the surprise of many in the industry, a chain of inspiration has been shown to link the exploits of British women leading the world on road and track not only to recreational riders and racers, but everyday women cyclists for whom Lycra and gritted teeth are anathema.

Caz Nicklin is now a veteran of the modern women's cycling movement. About seven years ago, however, she faced a dilemma familiar to millions. "I needed exercise and to save money; cycling made sense but I was scared on the roads and didn't want to have to wear Lycra," she recalls. "But then I saw a woman cycling in the park who looked amazing in normal clothes and I thought, I can look like her."

Back then, fewer people cycled regularly and the proportion who were women was lower. Today, according to British Cycling, of those people in England who cycle once a week, around 525,000 (27 per cent) are women. Of those who cycle once a month, 1.2 million (33 per cent) are women. The number of commuters among them has risen by 40 per cent since 2008, a boom which Nicklin believes is being significantly boosted by cyclists like her, who lend cycling the image of a "normal", accessible pursuit.

"When I started, it was still a trend bubbling under the surface but now it's become so much more mainstream," says the 34-year-old, who started the London Cycle Chic blog and online store in 2008, and is the author of a new book, The Girls' Bicycle Handbook. "It's about representing a desirable image of cycling that's encouraging to more women."

Nicklin was pleasantly surprised to observe a significant and permanent rise in sales and interest after Team GB's women won five medals to the men's six in London, including three golds on the track. "Something happened during the Olympics," she says. "I can't quite put my finger on why, because sporty cycling can seem so far removed from the everyday, but somehow it put something out there that there was a positive vibe about cycling – and that was contagious."

This is music to the ears of professional role models. "Sport should always look at how it can get involved at the grass-roots level, because only then can you say you're useful to society," says Pooley. "Otherwise, riding around in circles is fairly pointless."

It's an approach being embraced by the organisers of the Women's Tour of Britain, which starts in Northamptonshire on 7 May. Guy Elliott is a dedicated cyclist who once ran a cycling academy for children. Girls were equally as interested but Elliott became frustrated that their chosen sport treated them as "second-best". As the director of SweetSpot, the events company which revived the men's Tour of Britain 10 years ago, he set about creating a tour for women. "The barrier in continental cycling has always been tradition," he says. "Big races such as the Tour de France thrive on their history. Britain is now viewed as an innovative country in cycling and we have a genuine opportunity to create our own history. There's no reason why the Women's Tour can't be the best in the world from year one."

Elliott has engaged authorities along the route to stage festivals aimed at engaging girls and women. But for his grand vision to work, he needs corporate investment and sponsorship.

In France, this year's La Course is a fresh start after the fraught history of the Grande Boucle, formerly known as the Tour Cycliste Féminin, a women's stage race born in 1984 that spluttered to a cash-starved halt in 2009 (when Pooley won). Yet enlightened backers such as Honda, which sponsors the Belgium-based Honda Wiggle women's team (its riders include British Olympic winners Laura Trott, Dani King and Joanna Rowsell), still remain the exception. "Less than 1 per cent of commercial sports sponsorship in the UK goes into women's sport, which is a damning, shaming statistic," Elliott says. "And this at a time when every FTSE 100 company preaches a diversity agenda."

But, the 96 male chief executives among those 100 companies might argue, there isn't the demand to justify serious investment. To which women say: balls. "It's so easy for people to suggest that," says Pooley, "and it's hard to prove otherwise – just as it's hard for them to prove their case, because there aren't the viewing figures to prove it."

The exception is the Olympics. More than 5.7 million people tuned in watch Mark Cavendish fail to win the men's road race in London. The next day, 7.6 million people watched Lizzie Armitstead win silver in the women's event. "So many people contacted me afterwards saying they hadn't realised women's racing was so exciting," Pooley says. "They asked me where they could watch more, and I had to say they couldn't." This year, ITV4 is extending its coverage of the men's Tour of Britain and Tour de France to their new sister events.

Joanna Rowsell says her continental teammates at Wiggle Honda have already been impressed by the level of roadside support in Britain. "We raced in London last June and they all said how amazing it was that we had so many people in the crowds. It's such an exciting time to be a female cyclist."

Between Rowsell's and Caz Nicklin's ends of the cycling spectrum, women are desperate for more opportunities to ride and race. Victoria Pendleton lends her name and celebrity to the increasingly popular Cycletta series of women's bike rides, while last year, British Cycling and its partner, Sky, set out its ambitious vision to get a million more women riding every week by 2020. In 2010, it launched its Breeze Network of events for all levels. Natalie Justice, who runs Breeze, has a background in developing women's football. "In both cases, women just want to have a go," she says. "And the past 12 months have been a massive breakthrough. The industry is finally switching on and realising the demand."

Whether demand or supply comes first, persistence is key to cultivating women's cycling. Wiesia Kuczaj found this at a local level at Herne Hill velodrome, site of the historic 1948 London Olympics. Four years ago, the amateur racer, who works in cycling public relations, began putting on weekly women's nights at the velodrome. "Sometimes just one or two women would turn up but we always ran the session because continuity helps development. Now we get up to 50 every week."

The message is clear: invest and they will come. Yet, if inertia in the industry and cycling establishment is finally being challenged, the biggest barrier to greater participation, particularly in our cities, is fear. According to a Government survey on transport attitudes published last July, two-thirds of women say the roads are too dangerous to cycle on. Never has this fear been greater than during a bloody fortnight last November, when six London cyclists were killed. Their deaths prompted a national scandal, with "die-in" demonstrations and the controversial deployment by the Metropolitan Police of 2,500 officers at dangerous junctions. After the fourth death, an image of one felled cyclist's mangled bike appeared on the cover of a million copies of the Evening Standard, London's free newspaper. The headline: "Woman Killed in Latest Horror."

Few cyclists have had a clearer view of Britain's boom in urban cycling than Stephanie Bartczak, a French bike messenger who has worked in London for 15 years. She remembers an influx of women on bikes after the 2005 terror attacks in London spread fear of public transport. Now a different sort of fear could send them back underground. "I remember feeling in more danger at the time of the [cycling] deaths because there was so much in the press," she says. "A lot of the coverage was, oh, yeah, it's the cyclists' fault they're getting killed, and I felt the behaviour of drivers got even worse."

The coverage also masked less gloomy statistics. By the end of the year, 14 cyclists had died on London roads, which is 14 too many but the same number who died in 2012, and fewer than the 16 cyclists who died in 2011. Meanwhile, the number of London cycle journeys continues to soar, to more than half a million a day, or double the number of journeys made in 2000.

But figures alone, which tell similar stories in cities with smaller bike booms, won't banish the perception of risk. Rachel Aldred is a cycling sociologist and senior lecturer in transport at the University of Westminster. "If you're going to tell people cycling is safe but their experience is close overtakes by HGVs, it's not comforting," she says. "We need to create an environment that is not just objectively safe but which feels safe."

Last December, Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London, announced plans for a comprehensive grid of quiet, bike-friendly routes that he hopes will "de-Lycrafy the bicycle, reduce the testosterone levels of cycling, and move towards a continental-style cycling culture, where cycling is normal". Across the country, local authorities are similarly waking up to the need for improved infrastructure – and not before time.

More still needs to be done to change attitudes on both sides of the windscreen, and to tackle the threat of lorries, which were involved in nine of the 14 deaths last year. Also troubling is the widely reported (and therefore off-putting) disproportionate number of female victims. In 2009, perhaps the worst year for women cyclists, eight out of 13 cycling deaths in London were women killed by lorries.

Perceived wisdom tells us women tend to be more nervous and cautious, and that this puts them at greater risk, particularly around larger vehicles. But, Aldred says, "I'd worry about saying women are doing the wrong things because, ultimately, when you look at these deaths they are often people who are experienced, competent riders. When you look at who's responsible for these deaths," she adds, "it's overwhelmingly men. Are people investigating what that says about driving styles?"

As the culture of cycling changes, and the safety debate rolls on, riders waiting for a better deal have power only over their own bicycles. For Caz Nicklin, training, which is subsidised for new riders by many authorities, is the best way to feel safer.

For Pooley, Vos, Armitstead and the rest, being seen remains the biggest battle. As the first female winner at the Tour de France steps on to the podium for La Course in July, it's not clear whether a young, nameless man will be required to kiss her. Regardless, this time the revolution will be televised.

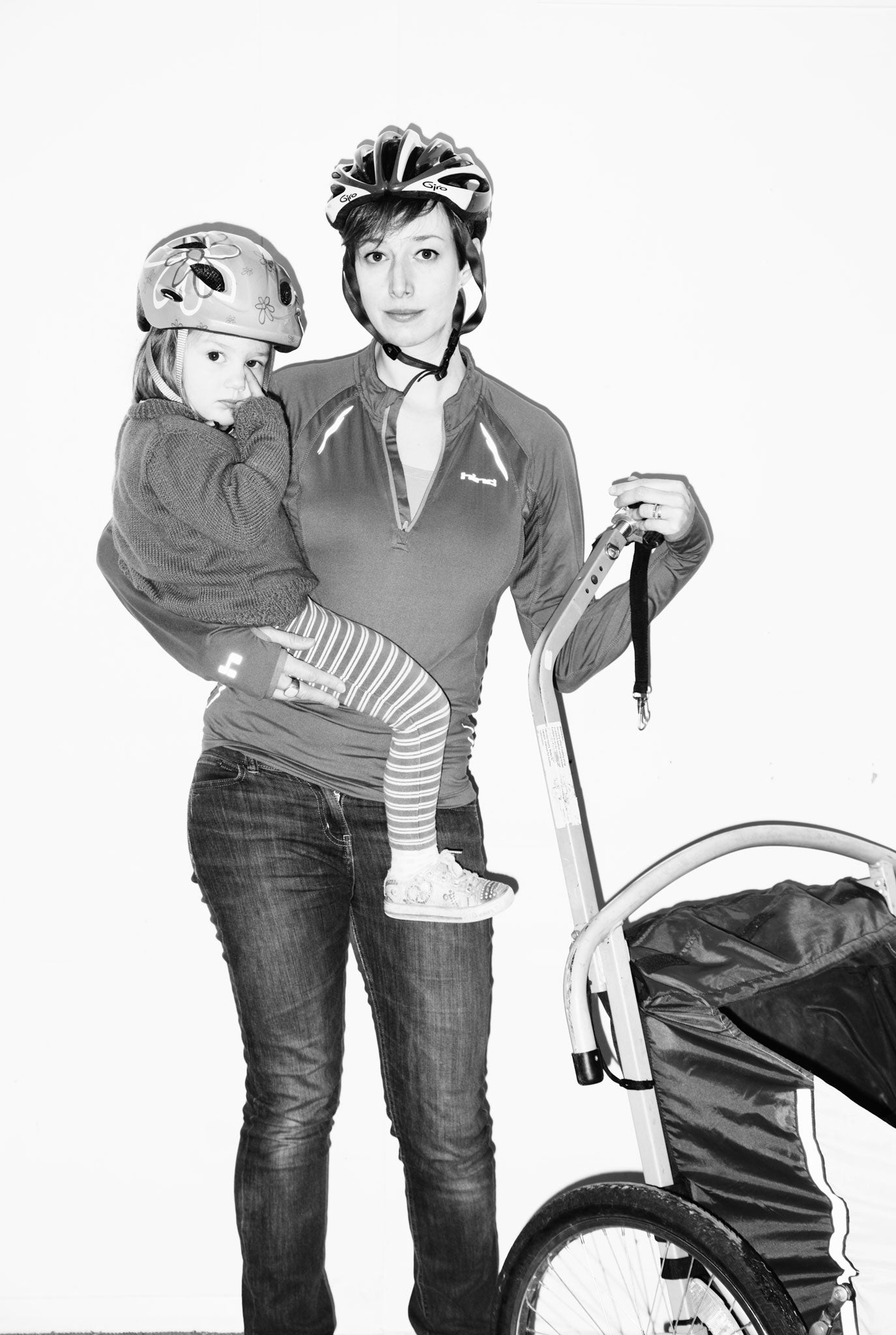

Portraits taken at the Herne Hill Velodrome

Stephanie Bartczak, 39

Bicycle courier

"Only one in 30 couriers in London is a woman but there's never a feeling that we're inferior. I've been doing this for 15 years and when I've done a 10-hour day in snow or rain, and covered up to 70 miles, nobody's going to turn around and say I'm not as good as them.

"I have a courier friend in Berlin who's worked all over the world and says the only place she's been scared of cycling is London. But then other people say it's fun to ride here. I don't know why I still do it because the money's not as good as it used to be, it's tiring and it's dangerous. But it's easy go get hooked. It's the freedom of riding a bike and a sense of community you don't get anywhere else."

Jess Bowie, 29

Everyday commuter

"I cycled as a student in Cambridge because it was the only way to get around. When I brought my old bike to London, the traffic and size of the place was a shock, but you get used to it. And there are no downsides – it's free and gives me 50 minutes of exercise a day.

"If my commute were longer I'd probably change once I got to the office, but luckily I can get away with cycling in my normal work clothes. I'm loathe to say it but often women care more about how they look, so might think cycling will make them a bit disheveled. But if more of us do it, and female commuters look out the bus window and see women like them on bikes, it would definitely help."

Wiesia Kuczaj, 32

Amateur racer

"I started competing about six years ago and I used to have to travel all around the country to find races. Now in summer I can race almost every night of the week just in London. The whole scene is becoming a lot more professional, with more teams and sponsorship. It's going in the right direction.

"Having the Women's Tour of Britain really takes it to the next level and I hope it filters down so we see even more leagues and grass-roots initiatives. From where I am, women's cycling is growing exponentially. We're also showing that there's a friendly side to the sport – it doesn't have to be macho."

Rebecca Hinshelwood, 34

School-run mother

"Jemima's five, Bethany's three and I'm 20 weeks' pregnant – and we cycle everywhere. Depending on how many children are with me, I put them in the trailer or bike seat for the school run. Or now I can walk and they cycle – neither of them has stabilisers.

"I'm usually fine but if I do feel intimidated on a day when everyone's being mental, I just step on to the pavement. Probably the most hairy moments come on the school run from other mothers who are driving.

"We have a car but I don't want my kids to think the only way to get anywhere is to be dropped off. It's good to get fresh air and exercise, and I want them to grow up believing that."

The best cycling gear

Kryptonite Evolution, £50

The more regularly you ride (and the more valuable your bike), the more you must invest in a lock (pictured above). This Kryptonite D number carries the Sold Secure gold standard.

Chrome Citizen Messenger, £132

Messenger bags take some getting used to but are voluminous, comfortable and leave smaller sweat patches than rucksacks. Chrome’s bags are both waterproof and rugged.

Sidi Genius, £170

Stiff-soled shoes aren’t always practical for walking around, but nothing will do more to add power to your pedalling. Sidi is a top Italian brand

Linus Sac Pannier, £50

Panniers needn’t be style disasters, as this wax canvas bag (pictured above) proves. Inspired by vintage boat bags, it comes with rack hooks and a brass padlock to secure it to your bike.

Bern Lenox helmet, £50

Skater-style helmets are de rigueur among everyday commuters. This jaunty number, available in several shades, has a female-specific fit.

Knog Blinder 4, £35

Do away with cumbersome and costly triple-A batteries with Knog’s range of fiercely bright USB lights. Just plug them in to your computer to charge.

Ana Nichoola mitts, £29

High-end, goat-skin gloves (pictured above) from the pioneering women’s brand founded by London racer Anna Glowinski.

Oakley Radar, from £175

Lizzie Armitstead launched an appeal after losing her lucky pair of sunnies at the 2012 Olympics. The choice of pros and amateurs alike looks the part and won’t steam up.

Lazer Helium, £180

The gold-plated GB stars of Team Wiggle Honda ride under these lids, which include a unique adjustment system and water-based pads for cooling and comfort.

Islabikes, from £130

Kids deserve better than the hulking machines you grew up riding. Isla Rowntree’s bikes (pictured above) are light, well made, and come in sizes for all ages.

Hamax Kiss, £60

Norway’s leading child-seat firm makes a range of sturdy, comfy units. The Kiss fixes to bikes with or without luggage racks and is for kids older than nine months.

Christiania Light Classic, £1,898

Trailers are cheaper, but cargo bikes such as this are useful when the children are a little more grown. This Danish model is designed for two – or several more shopping bags.

Cycling statistics

525,000

Of those in England who cycle once a week, more than half a million (27 per cent) are women

40 per cent

The number of female bike commuters has risen by 40 per cent since 2008

7.6 million

watched Lizzie Armitstead win silver in the London 2012 Olympic women's road race (2 million more than watched the men's race)

1.5 million

British Cycling wants to treble the number of women riding every week by 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments