A sealife mystery is tearing a community apart – but authorities have stopped looking for answers

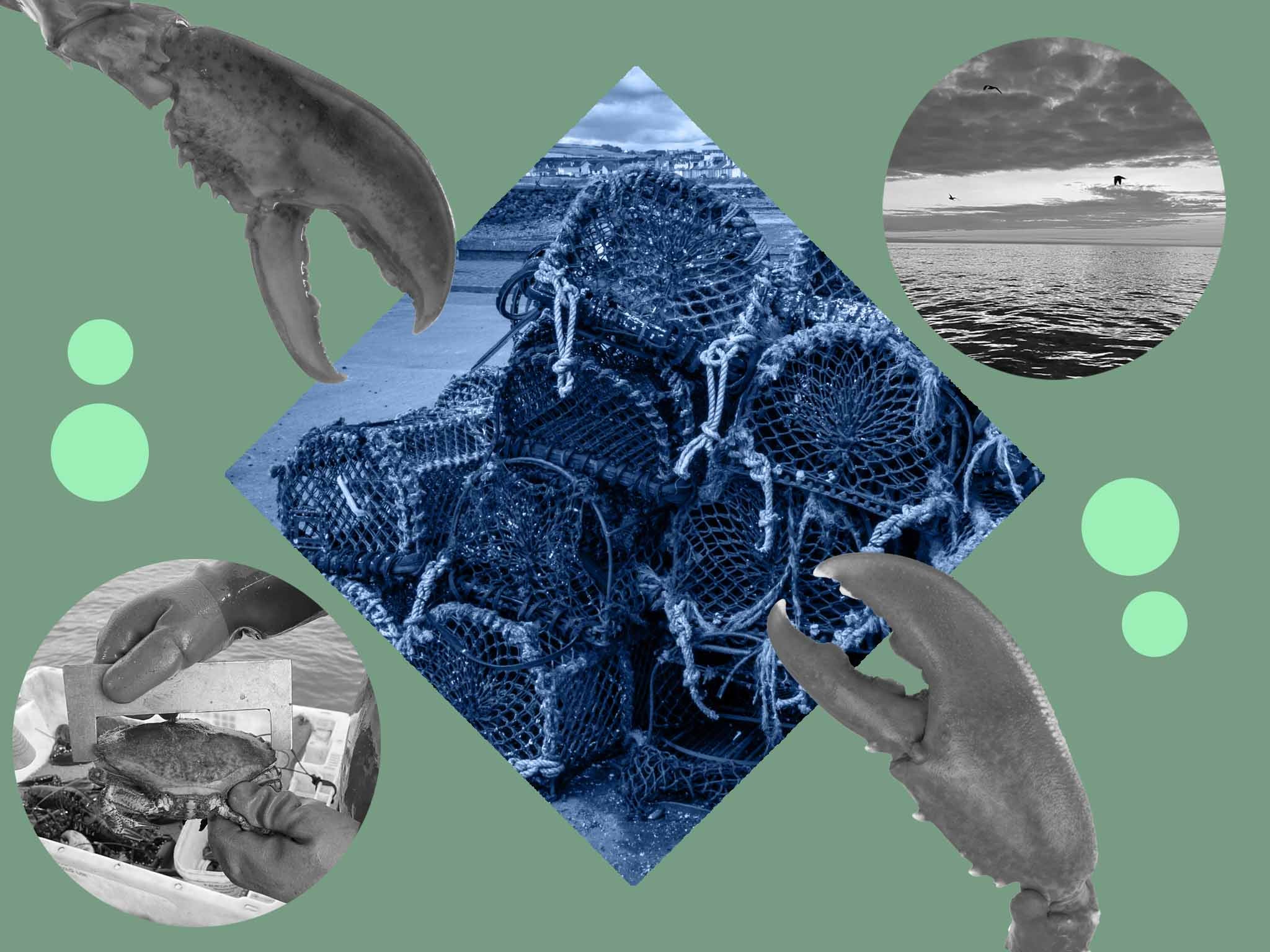

Special Report: Wave upon wave of dead lobsters and crabs have littered the shores of the northeast coast over the past nine months, but the official explanation doesn’t stack up. Anna Isaac finds fishermen and activists determined to get to the bottom of the environmental disaster before it’s too late

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.She may have left the police force, but former officer Sally Bunce has found herself back on the case once again. “This is a crime scene,” she says. “It merits criminal investigation. I got used to seeing dead bodies on shift. And now I’ve been looking at more dead bodies.”

What’s different this time is the victim in question. Bunce – now an environmental activist in her early 50s – is talking about crabs. Since October last year, the corpses of crabs and lobsters, lugworms and razor clams have littered the beaches of England’s North Sea coast on a 50-mile stretch from the mouth of the Tees down to Whitby and Scarborough.

As videos have spread online of the mass “die-offs”, concern has risen among activists, scientists, fishermen and divers about a string of events that threatens livelihoods and sealife itself.

They say the chief suspect is a toxic compound linked with industrial processes they believe has been stirred up by dredging, the lifting of sand and sediment from the sea floor. They have pointed the finger at work associated with the management of Teesport, run by PD Ports and ultimately backed by a financial firm with $725bn (£613bn) in assets under management. PD Ports has said it does not believe dredging is to blame.

But there’s another major political sensitivity in play: the future development of a Brexit freeport. This would require significant amounts of dredging cheek-by-jowl with sediment that campaigners believe caused the die-offs.

Further investigation into what went wrong could delay development, officials admit, and make it harder to sell the twin flagship policy of freeports and levelling up. The area that has seen this environmental carnage epitomises the “red wall” concerns of Westminster and No 10: traditional labour strongholds that turned blue at the last election.

Authorities, meanwhile, have pinned the blame for the die-offs on a different culprit: algae. A report from the Department for the Environment and Rural Affairs considered the mass deaths to be the result of a naturally occurring algal bloom. But this has raised more questions than answers, with concerned locals now crowdsourcing funds for their own scientific investigation to challenge the government’s findings. “They have no hard evidence,” says Bunce. “We need a proper investigation.”

‘To us it’s a way of life’

Shortly before 3am, around 30 nautical miles from the mouth of the Tees, Adrian Noble steers his fishing boat Olivia Rose out of Whitby marina and sets his course for the dimly lit horizon, as he has done for 40 years. Noble knows already that his haul of crabs and lobsters will be barely a quarter of what it was last year. Up the coast in Hartlepool, catches are down by 90 per cent.

“You used to get pots full of velvet crab, brown crab,” Noble says. “Now it’s like heading into a desert. It’s unbelievable what’s happened and you’re not getting any answers from anybody.”

Whatever the trigger for October’s die-off, the problem has “followed us down the coast”, he says, carried south on flood tides from the Tees to Whitby and, beyond it, Robin Hood’s Bay, covering an area fished by dozens of boats.

On the Olivia Rose, Noble works with fellow fishermen Jonathan Parkin and George Lamplough to lift a clutch of lobster pots. Noble draws up the line and flings the pots to Parkin, who catches them before drawing out any catch and tossing old bait to the delight of clamouring gulls. He restocks and closes the pots with the help of Lamplough, who then stows them on deck. The stack is then released back into the hunting ground for the coming days.

Fatigue and stress line Noble’s face. The weekly fuel bill of £800 has doubled in the past year and costs are drowning out profits. For most fisherman, their job is indivisible from their identity and heritage: “This is my life”, says Noble.

He places his pots on a wiggling line that mirrors that of his father’s. Others keep pots in a straight line; Noble believes that twisting and turning into the crinkles of the topography has been key to success over the decades.

Between hauling up the pots, Noble, Parkin and Lamplough pick out their dream houses in Robin Hood’s Bay: “I’d pick that one,” says Lamplough, indicating a relatively remote spot, “because it’s far enough from these madmen”, he quips, pointing at his shipmates.

But for all the moments of humour there’s growing a sense that the boat is now running on borrowed time. Historically, all aboard have earned above the living wage. Now it’s hard to see how they will meet the cost of keeping the boat seaworthy.

“Something pretty damn awful has happened,” says Lamplough. “It’s not hard to see that.”

As he speaks, Lamplough measures lobsters, returning those under 87mm because of environmental regulations, and notching the tails of female lobsters – known as “hens” – who are laden with eggs, in order to preserve the breeding stock. “That’s us doing our bit,” he says as he puts one overboard.

Returning to Whitby after eight hours at sea, their catch consists of just two small velvet crabs, a handful of brown crabs, a small haul of lobsters – down 75 per cent – and no green crab at all. The biggest worry? “There’s hardly any babies,” says Noble, shaking his head at the lobsters.

“People don’t understand that we’re farmers of the sea,” says Parkin, a veteran of more than 20 years in the army. “To us it’s a way of life, and we want to find out what’s gone on. If this has been man-made, man should be held accountable for it.”

In Hartlepool, matters are even worse. Fishermen describe catching little more than thin air and silt for weeks at a time since October last year.

‘It was hard before – now it’s impossible’

For the government, the case is closed – a huge growth in algae, specifically the Karenia mikimotoi species, was responsible for depleting oxygen in the water and causing the mass die-off last October. But although this algal bloom, as suggested by Defra in its report in May, is a possible explanation, it is not a straightforward one.

First, in other incidents with similar blooms, fish gills have been damaged. Scientists suggest it would be unusual for this not to have occurred, given the scale necessary to have wiped out such a large number of creatures on multiple occasions. However, no sightings have been reported.

Second, a bloom does not explain why these die-off events are repeating despite conditions that do not appear conducive to algal blooms, scientists say. Defra’s own chart shows a significant drop in temperature in the lead-up to April’s die-off event, yet also claims to illustrate ideal conditions for an algal bloom that normally requires warmer seas.

Defra’s argument is that warmer-than-usual temperatures in September helped to grow the algae, which was then killed by the colder shift in early October, causing it to fall towards the seabed and kill crustaceans.

Blooms tend to be relatively short-lived. It is not impossible for them to happen over a long period with repeated severe intensity, but it is very unusual, according to scientists.

The original satellite imagery report produced by Plymouth University – examining pigments to determine the type of algae – notes risk rather than confirmation of an algal bloom, and does not confirm that such a bloom would be toxic.

Likewise, Defra’s testing of dead crustaceans shows algal toxins were present in some instances but does not definitively prove Karenia Mikimotoi at a level that would have killed crustaceans at such a scale.

Shifts in language from risks and signs to certainty and conclusion in reports have also threaded doubt through affected communities. Stan Rennie, a Hartlepool fisherman, sent photos of what he considered to be scrap rust pollution to the Environment Agency (an agency arm of Defra), only to find it used as evidence of an algal bloom in communication from an official at the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS). These photos were not referenced in Defra’s later, final report.

A separate piece of correspondence to Rennie says this was found by the authorities to be scrap rust, as he originally contested. Rennie is relying on his pension to get by but it is not sustainable. He shows a list of boat adverts that display fishermen giving up a job that is their heritage and home in one.

Some are having to visit food banks in order to survive. One says he has become suicidal since the die-off: “It was hard before. Now it’s impossible. I’m failing to provide for my family. I see no purpose. I’m there to put food on the table.

“I used to give people some extra catch as a favour. Now I catch nothing, I’m having to go to the food bank.”

Unconvinced by the algal bloom theory, fishermen and activists have suggested another cause: toxins brought up from sediment in the river bed by dredging. This could, they say, explain how the issue has “killed things on the bottom” but not shown harm to some other species – a characteristic Defra acknowledged in its report.

The Tees has a long, toxic history as an artery of Britain’s industrial revolution and, like the Tyne to its north, the river has a soup of contaminants buried beneath its bed. Now they fear this could be being brought to the surface by work for the flagship Tees freeport.

‘The truth was we did not know for sure’

The site was visited by Rishi Sunak and Boris Johnson in March last year as they touted the policy in which goods can be imported with a range of tax breaks – a brainchild of the then chancellor. Last year it was confirmed by Conservative Tees Valley mayor Ben Houchen that a freeport would be built on Teesside.

The project will be built by Tees Valley Combined Authority and a related network of companies. It would, in theory, create 32,000 jobs. It would also require some of the deepest ever dredging of the Tees, scheduled to take place in September. The site covers 4,500 acres in the heart of what has become part industrial museum, part scrubby concrete in Redcar.

It is cheek by jowl with areas that have been transformed into nature reserves on the sites of the some of the world’s heaviest historical polluters. Seals sunbathe in the waters near power plants.

PD Ports’ office on Queen’s Square in Middlesbrough is lined with wooden panelling and listed by Historic England. Tracing its roots back to Wales in 1840, the company has been tied to Tees port since the 1990s and now owns the port of Hartlepool among others.

It even has its own harbour police force, which has operated in the ports of Tees and Hartlepool since 1904. This underlines its balancing act as referee and player by running the commercial operations at the port while being the guardian of the Tees river mouth.

Jerry Hopkinson, chief operating officer and vice chairman of PD Ports, is between triathlon training sessions when he meets The Independent, driving between his office and the harbour master’s in his immaculately clean Tesla mid-interview.

He’s eager to convey that this is a company that “takes its responsibilities incredibly seriously”.

And those responsibilities are considerable. The commercial arm of the port infrastructure also holds a statutory responsibility to act as environmental guardian of the Tees. The firm is owned by Brookfield Asset Management, a Toronto-based financial company with $725bn of assets under management. Brookfield tried to sell PD Ports last year, but gave up after a legal fight with Houchen in which the mayor was accused of trying to hold the port to ransom.

Hopkinson is aware that PD Ports is being blamed by some, but says the firm’s dredging cannot be to blame because no deep dredging – known as “capital dredging” – has been carried out in the past two years.

“Our role as the statutory harbour authority is something that’s very precious to us. It’s right at the heart of our business. We would not act to prejudice that,” says Hopkinson.

He plans to offer fishermen and activists a precise explanation of the dredging taking place, how it is done and how it is recorded and controlled. But Hopkinson is emphatic: “I don’t believe that in any way something strange has happened with the dredging.”

Joe Redfern, a marine biologist who is working on a lobster hatchery in the area, says even dredging at a much shallower depth for maintenance – to stop silt and sand building up at the mouth of the river – could have released a trigger for the die-off, because its intensity has changed. He calculates that as much as two thirds of the annual allowance might have been moved within a few days. However, PD Ports denies this, claiming that only around 5 per cent of the allowance was moved.

The chemical suspected of being released by the dredging is pyridine, used in production of herbicides, pesticides and in mixtures applied to the underside of boats to stop plants and creatures taking hold. It is also a common byproduct of steel and other fossil fuel industries. There is a history of pyridine production in the area.

It is not easy to prove conclusively that the die-off was triggered by a chemical toxin. There is no baseline measure of a toxic level of pyridine. At the moment, scientific evidence is focused on much smaller organisms, limiting the ability of scientists to read across its effects in larger creatures, such as crabs.

Tim Deere-Jones, a marine ecology consultant since 1983, who trained at Cardiff University, was asked to review Defra’s work by local fishermen. He used freedom of information requests to gather details of Defra’s data and spotted what he considered to be significant findings of pyridine.

“On the basis of the toxicological analysis that was done, I could only conclude that the relatively large amount of pyridine in the crab tissue was a potential causative factor on the basis of the information we had. I’m not nailing my colours to the mast and saying it can only be pyridine, because we have limited data,” he says.

A team of academics at Hull, York, Newcastle and Durham universities are now examining how much pyridine might kill or harm a crab. They are being crowdfunded by the fishermen. However, this too is difficult – it could be that pyridine is combining with something else in the water and the reaction of this cocktail of toxins has led to the die-offs.

If dredging is involved, it would not be the first example of how this kind of activity, even at maintenance depths, can have a major impact on the marine environment. Alex Ford, professor of biology at Portsmouth University, says he has uncovered examples of harmful toxins released into seawater by dredging.

There was clear political pressure brought on us to just find an answer

“Between them [CEFAS] and the Environment Agency, they’ve concluded it was an algal bloom that just happened to be toxic to those crustaceans, which is conceivable,” Ford says. “But that’s not to say that dredging activity might not be involved in some ways.

“I’m not so concerned that there’s a conspiracy going on, but there are a lot of these die-off events going on around the UK over the last couple of years. There’s a lot of dredging that goes on around the UK as well.

“I feel we might be missing the bigger picture. But since there’s not widespread monitoring going on because of budget cuts to the Environment Agency and to CEFAS, it’s hard to form an accurate picture and come to conclusions when events like this happen.”

Alastair Grant, professor of ecology at the University of East Anglia, said it was possible that an algal bloom was responsible, but there are still questions outstanding from Defra’s report: “The presence of pyridine in crabs is unexplained – and it would be helpful if Defra could make more detail available on the analytical methods used and the concentrations measured.”

It is these unknowns that make the official decision to settle on an algal bloom and not investigate further so concerning to locals. Scientists who worked on the investigation say their findings were not as definitive as has been suggested by the government.

Two officials with knowledge of the investigation carried out by Defra and related agencies – the Marine Management Organisation, CEFAS and the Environment Agency – feel too much weight was given to the algal explanation. It was not conclusive, “yet politicians have lent on the report to suggest it is an open and shut case”, one says.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one government scientist who worked on the final joint report says: “We were not confident that the algal bloom was the absolute cause in the manner it has been presented by politicians. The truth was that we did not know for sure and we still do not know for sure. The second truth is that we’re unlikely to be given the necessary resources to find out.”

Their concerns are echoed by a second senior official, who says there was no desire for a cover-up in Defra or related agencies, but there had been huge pressure to find a definitive answer, and quickly.

“There was clear political pressure brought on us to just find an answer and then the least politically sensitive hypothesis was given most prominence,” they say.

They claim that the pyridine section in Defra's final report was rushed and trimmed, something that appears to be supported by a series of spelling errors and inconsistent formatting. They do not consider this to be a conspiracy, or a cover-up, but “poor handling” of a report that amounts to “inconclusive evidence”.

A Defra spokesperson does not address these specfic allegations of political pressure.

However, they say the department and related agencies carried out a “thorough investigation” and “concluded that a naturally occurring harmful algal bloom was the most likely cause of the incident”, adding: “We ruled out a number of potential causes including chemical pollution, sewage, animal disease and dredging.”

PD Ports says any suggestion of a cover-up is wide of the mark. “There’s a sense that there’s a laxity in terms of scrutiny from agencies. I just genuinely don’t sense that,” says Hopkinson.

‘I’ve not got much left’

In Westminster, however, Conservative MPs from the region are not joining the push for more answers. Sir Robert Goodwill, MP for Scarborough and Whitby, says “the balance of the science” points to an algal bloom, while Jacob Young, who represents Redcar, says: “There comes a point where, having asked every question and explored every avenue, I must defer to the expertise of the scientists at Defra. This was an incredibly unusual and alarming event but a result of a rare, naturally occurring phenomenon.”

Hartlepool MP Jill Mortimer does not respond to requests for comment, but a post dated 27 June on her Instagram profile reads: “I join with local fishermen in the belief that we need to look again at the cause of the crustacean deaths along our coastline”.

Mr Young raised the issue with Boris Johnson at Prime Minister’s Questions on 8 June, asking about compensation for fishermen. Mr Johnson responded: “I can tell him that we have ruled out chemical pollution, but we are making another £100m of investment, including in communities such as his, and working with the fishing industry to help it to recover from this problem.”

But that £100m Seafood Fund is not new money – it was pledged years earlier and will not be a response to the die-off event. “We won’t see a penny,” says Whitby fisherman Noble.

For Houchen, something of a poster boy for the Tories’ pledge to “level up” the nation, the issue is difficult politically on a local and national level.

He has put himself at odds with the view of his Conservative colleagues that a cause has been identified, telling The Independent: “I don’t think you can ultimately be satisfied with a report that cannot confidently identify the causative factor for this incident. I say this without criticism of the scientists and agencies conducting the research.”

It was not until January that he directly sought information on the die-offs, though he says he held frequent meetings with locals and officials.

The cause of the die-offs is potentially highly sensitive for Houchen’s plans. While no freeport dredging has taken place, his plans require millions of tonnes of sediment to be displaced, some of which, he told The Independent, has been found too toxic to be dumped at sea.

Meanwhile, animals are still dying in Teesside’s inshore waters, photo evidence suggests. Catches are drastically reduced and the economic pressure is becoming intolerable for many.

“I’ve not got much left for me in Hartlepool once I lose my boat,” says another fisherman, Paul Widdowfield. He plans to move to Pembrokeshire in Wales. He’s clear that he is “heartbroken”.

Solving this mystery “is on my bucket list”, Widdowfield says. For now, they, along with divers, activists and fishermen, await the results of their crowdfunded study, but they will not give up, even if they have to part with the tools of their trade.

“I need, before I die, to find out what’s happened,” he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments