Southwest Atlantic humpback whales bounce back from brink of extinction

Before whaling the population was about 27,000 and now it has nearly fully recovered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Humpback whales that frequent the southwest Atlantic have recovered from the brink of extinction and are now reaching numbers not seen since whaling started in the early 20th century.

Before commercial hunting, the global population was about 27,000 and now there are an estimated 25,000, meaning they have recovered 90 per cent of their numbers, a study has found.

At one point in the mid-Fifties there were as few as 450 animals left but now scientists say they should reach pre-whaling levels in the next 10 years. Co-author Dr Jennifer Jackson, from the British Antarctic Survey, told BBC News that the whales were now “flourishing”.

“We have a really nice story of success in the southwest Atlantic,” she said.

The whales spend winters in waters near Brazil and Gabon and in the summer they go to high latitudes to feed on Antarctic krill.

Dr Jackson said: “Modern whaling really got going in the southern Atlantic from 1904 onwards when the first whalers went down to South Georgia.

“They noticed that the waters were packed with whales. They initially hunted humpbacks because they were found in the near-shore waters and were very accessible.”

In the Sixties the whaling industry collapsed because there were no longer any whales to hunt and by the Eighties the population numbered just a few hundred.

Treaties were signed to prevent hunters killing them and other protections were put in place. The whales are now listed as being of “least concern” on the IUCN Red List of endangered species, but there is uncertainty about different subpopulations.

Humpbacks are believed to return faster than other whale species like blue whales because they mature faster, have a shorter gap between pregnancies and have centralised breeding grounds.

“Continued monitoring is needed to understand how these whales will respond to modern threats and to climate-driven changes to their habitats,” researchers wrote in the paper published in the Royal Society Open Science.

“The population status is much more optimistic than previously thought and abundance should reach its pre-exploitation level within the next 10 years or so, assuming mortality from anthropogenic threats remains low.”

It is illegal to approach a humpback whale within 100 metres by sea, or 300 metres by plane.

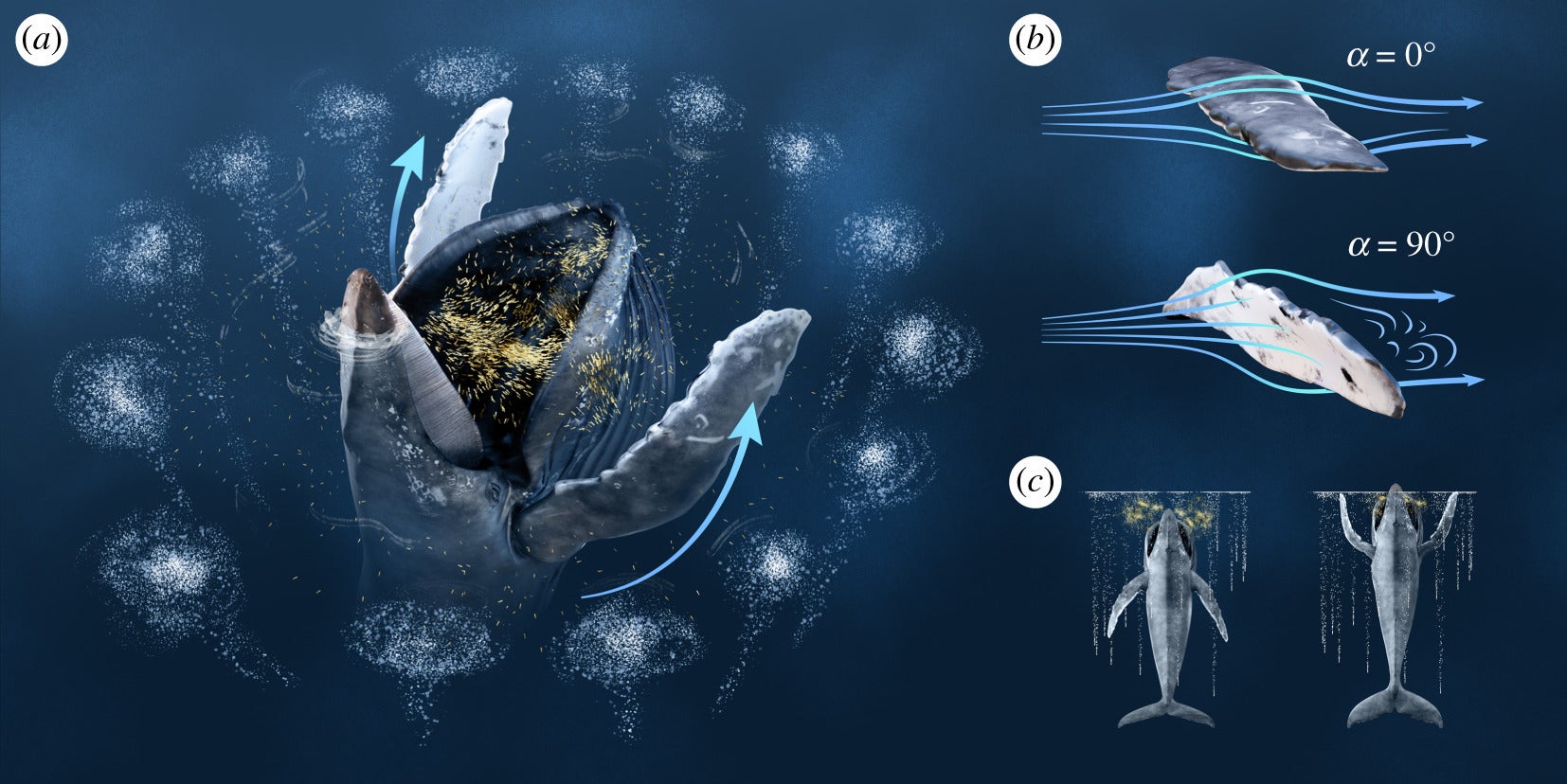

New research also shows these whales use flippers to trap their prey by swatting the water, according to another paper published in Royal Society Open Science.

Researchers from the University of Alaska Fairbanks were able to capture this behaviour on video for the first time.

Scientists monitored the whales over a period of three years in southeast Alaska and studied a behaviour called “pectoral herding” where whales use their flippers to generate bubbles and confuse their prey.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments