Science news in brief: prehistoric sea creature similar to duck-billed platypus discovered

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.No mammal may be more perplexing than the platypus.

Attached to its furry, otter-like body are four webbed feet, several sharp claws, a beaver tail and, of course, that duckbill. The females lay eggs and males sport venom-secreting spurs on their hind legs. One could only imagine how dumbfounded the first people to stumble upon these creatures were.

But if you were to wager a guess, they probably had a similar expression to that of Ryosuke Motani when he initially encountered the fossilised remains of the extinct marine reptile called Eretmorhipis carrolldongi.

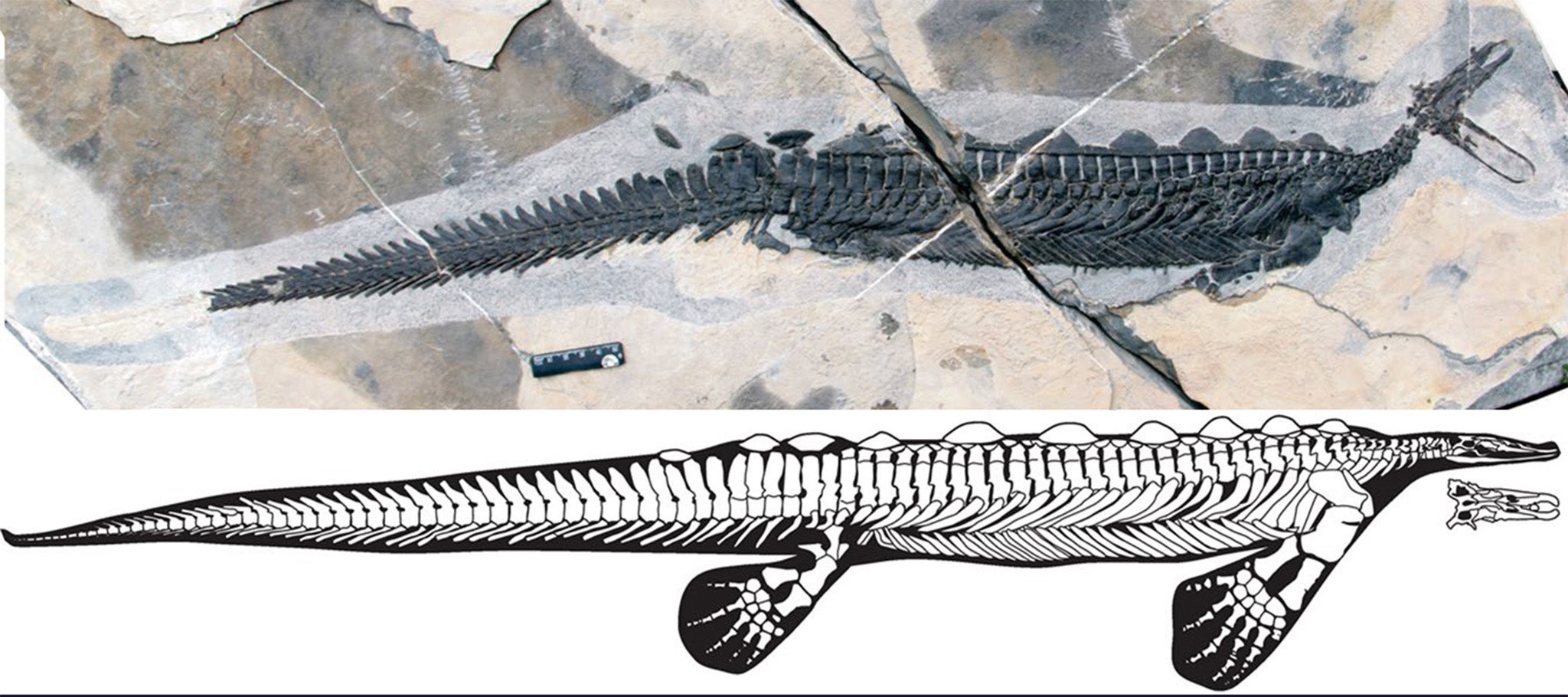

Like the platypus, this recently discovered prehistoric creature had a duckbill. But then nature made it even weirder, adding plates on its back like a stegosaurus, a long tail like a crocodile, large paddle-like limbs and a tiny head with teeny eyes.

“It’s a pretty strange chimera of features,” says Motani, a palaeobiologist at the University of California, Davis. “When I first saw it, I just said ‘What?!’ and didn’t speak for a while.”

Motani and a team of researchers led by Long Cheng, a palaeontologist at the Wuhan Centre of China Geological Survey, examined two specimens of the new species that had been found in China’s Hubei province. They published their findings in the journal Scientific Reports.

The first specimen was discovered about a decade ago, but it was missing a head. The second was unearthed by Cheng in 2015. Both specimens date to about 247 million years ago during the early Triassic, a time before dinosaurs ruled Earth.

Though the sea creature measured about 2 feet long, its eye sockets were only about 1 centimetre wide. That surprised the researchers. Prehistoric marine reptiles, such as the ichthyosaurs, typically had big eyes that helped them spot prey in the dim waters where they swam. The scientists concluded that E carrolldongi most likely did not rely on sight to catch its meals. Also, its small head ruled out the possibility that it made much use of sound underwater.

Because the snout looked similar to that of the platypus, the team concluded that the prehistoric reptile may have used its muzzle to feel out prey like a platypus.

If their finding is confirmed, that would make E carrolldongi the earliest known example of an amniote – the group that includes mammals, reptiles and birds – that uses touch over sight to hunt.

4.5 billion years old and ready for its close-up

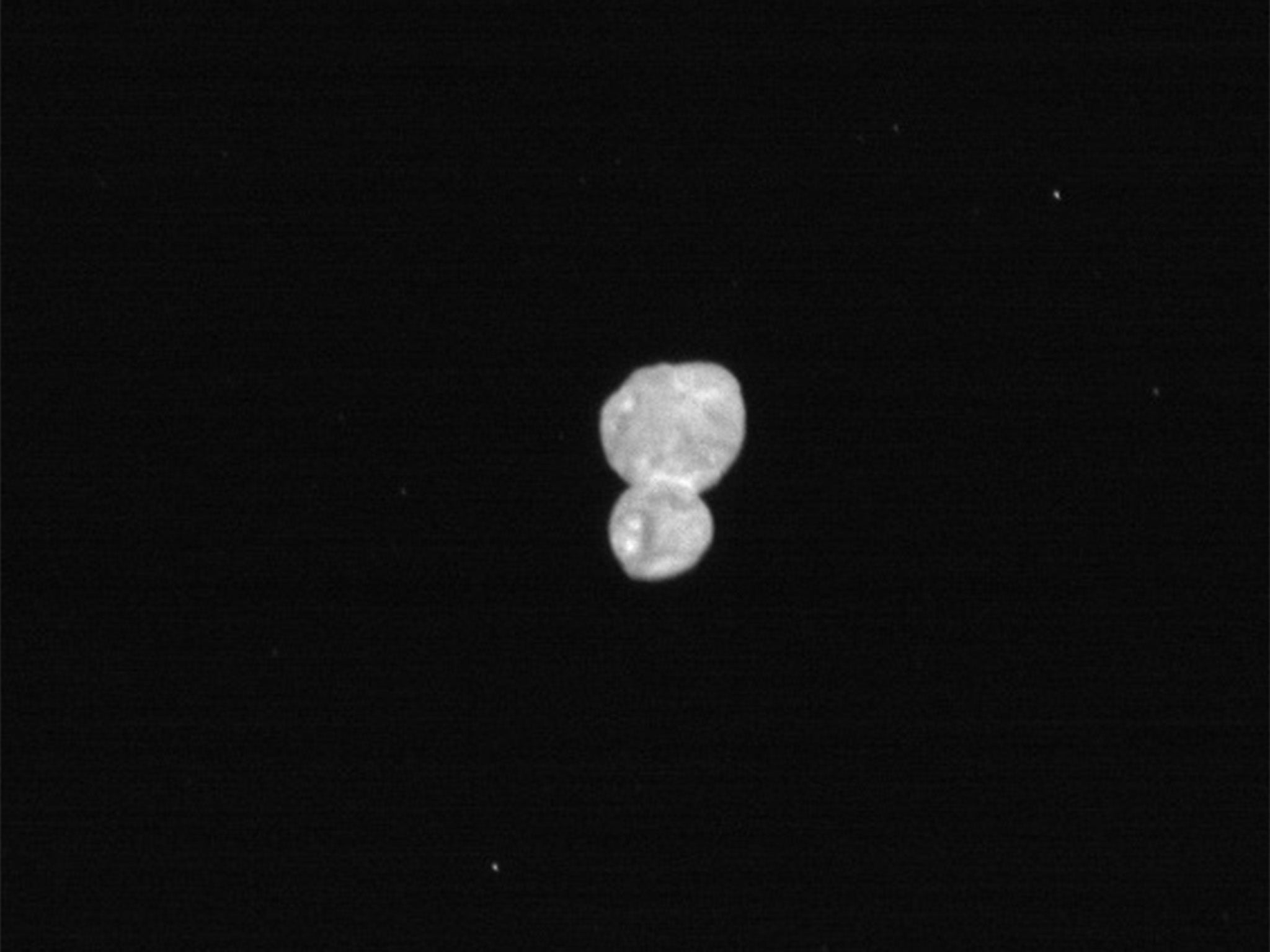

The icy rock that Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past on New Year’s Day is coming into focus.

On 24 January, the mission team released the sharpest picture of the 21-mile-long body known officially as 2014 MU69 and nicknamed Ultima Thule. Consisting of two roundish lobes that are fused together, it is believed to be an almost pristine leftover from the earliest days of the solar system, more than 4.5 billion years ago.

The spacecraft took the picture when it was 4,200 miles from Ultima Thule, just seven minutes before its closest approach. From this angle, the shadows are more apparent, revealing a deep depression on the smaller lobe. This could be a crater, a pit that collapsed or an area that was blown out when gases escaped from the interior long ago.

Scientists also can better resolve light and dark patterns on the surface, including a particularly bright collar where the two lobes connect.

Even sharper pictures could be sent back to Earth in the coming weeks as the spacecraft travels further into the distant solar system. New Horizons will continue to stream data from the flyby until late 2020.

Where sloths find these branches, their family trees expand

Look closely up in the trees of a shade-grown cacao plantation in eastern Costa Rica and you’ll see an array of small furry faces peering back at you. Those are three-toed sloths that make their homes there, clambering ever so slowly into the upper branches to bask in the morning sun. You might also spot them munching on leaves from the guarumo tree, which shades the cacao plants.

Scientists have long known that this tree is important to the diets of sloths. Its foliage is highly nutritious, available all year and easy for the creatures to digest. But in a new study published recently in Proceedings of the Royal Academy B, researchers report that a population of sloths with more guarumo trees in their cacao plantation habitat had more babies and were more likely to survive.

Their findings suggest that the tree’s presence can help ensure the health of sloth populations even in environments that have already been disturbed by humans, such as farms. It also shows how animals that have a specialised ecological niche, while traditionally thought of as vulnerable, can persist in changed circumstances as long as the resource they depend on is available.

For almost 10 years, Jonathan Pauli and M Zachariah Peery, professors at the University of Wisconsin, and their colleagues have tracked a group of sloths in Costa Rica.

While the survival of juvenile sloths was not linked to guarumo, the trees appeared to be important for the group’s adults. The five adults who died over the course of the study had markedly lower numbers of guarumo in their area than those that survived. At the same time, both male and female adults with more guarumo available to them had more offspring, the males in particular. That may be not only because of the nutrition the tree offers, but the visibility.

“Sloths are often seen sunbathing in the mornings,” Pauli explains, and if they are attracting mates by calling to them or making themselves visible, he says, “being in open trees might actually enhance those reproductive opportunities.”

Free trees? Many Detroit residents say ‘no thanks’

Deborah Westbrook, a lifelong resident of Detroit, would love a tree in front of her home.

Nonetheless, when representatives from a local non-profit came to plant trees on her block five years ago, Westbrook said “no”. So did more than 1,800 Detroiters – a quarter of all eligible residents – between 2011 and 2014.

Why the high rejection rate? In a study published recently in Society and Natural Resources, researchers found that the opposition does not arise from a dislike of trees per se. Most residents, the study found, appreciate the benefits of trees; these include alleviating air pollution, storm water run-off and higher urban temperatures, and helping to reduce stress, crime and noise. Low-income and minority residents often live in areas with the lowest tree cover.

The researchers, led by Christine Carmichael, a postdoctoral associate at the University of Vermont, conducted interviews with more than 40 Detroit residents. The biggest predictor of whether someone declined a tree, it turned out, was whether that person had negative experiences with trees – or with city workers or outsiders who, as one respondent said, “come in and try to ‘do good’, but only half do the job.”

From the end of the 19th century until the 1950s, Detroit was known as “the city of trees”, with more per capita than any industrialised city in the world. But by 1980, more than half a million trees had died. Of the 20,000 trees marked dead or hazardous in 2014, when Carmichael’s study began, the city had removed only 2,000 or so.

Carmichael has offered recommendations based on her research. Residents should be involved in at least choosing the type of tree they receive. Agencies should shift their metrics of success to include not just the number of trees planted, but also how engaged residents are in the process. Based on those suggestions, The Greening of Detroit, the non-profit group that came to Westbrook’s neighbourhood, expanded its youth employment programme, which trains and gives stipends to local high school students to maintain and teach residents about trees.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments