Study shows alarming cost of failing to act now on plastic pollution

Even if the world stopped producing new plastic, existing waste will continue to break down into tiny particles, doubling the pollution, a review of two decades of research warns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Microplastic pollution is expected to keep growing and could more than double by 2040, even if no new plastics are made, a major review of the last two decades of research has warned.

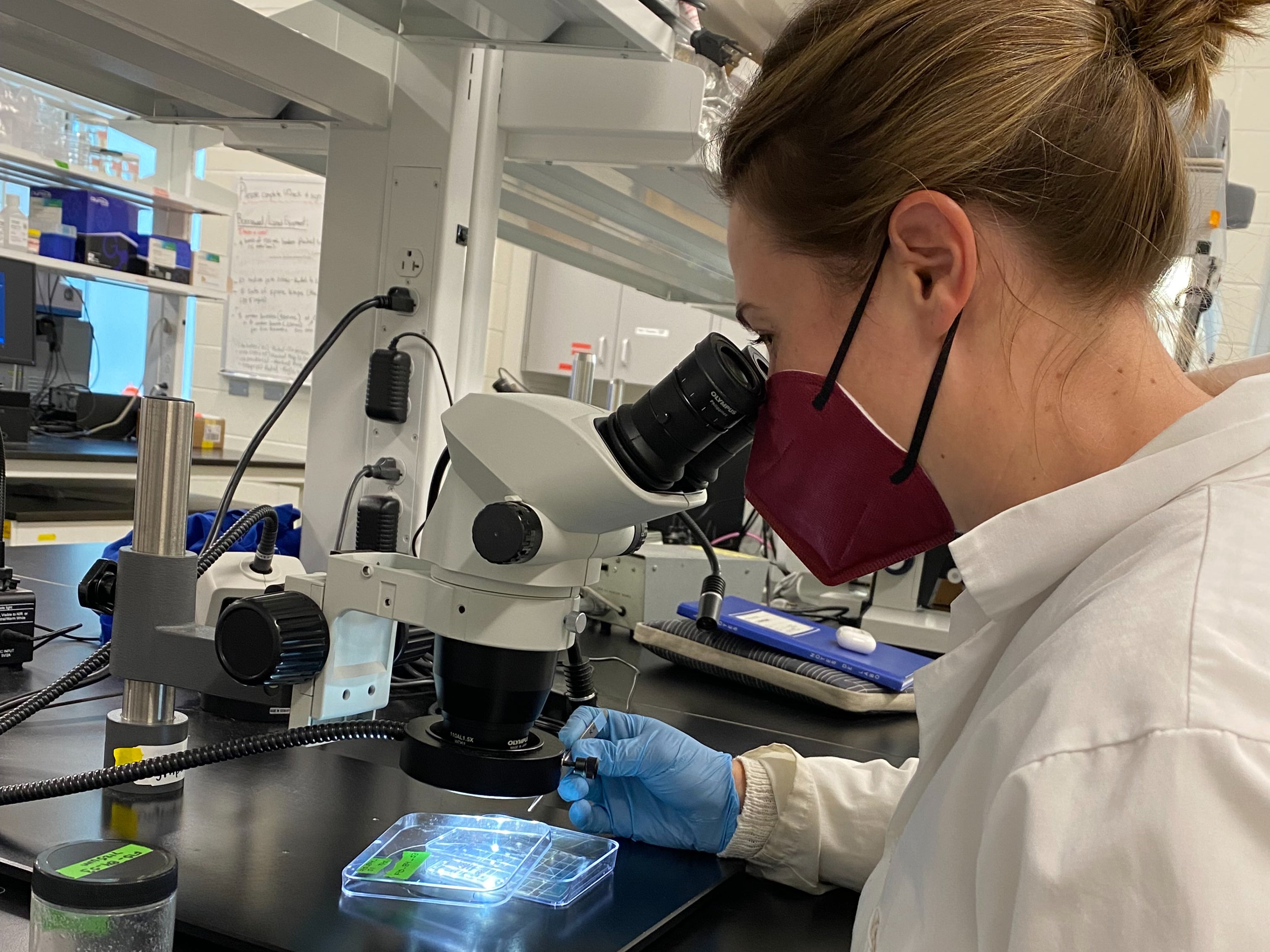

As existing plastic waste continues to break down into tiny particles, managing this growing pollution requires urgent action, scientists from University of Plymouth have warned in a study published on Thursday in the journal Science.

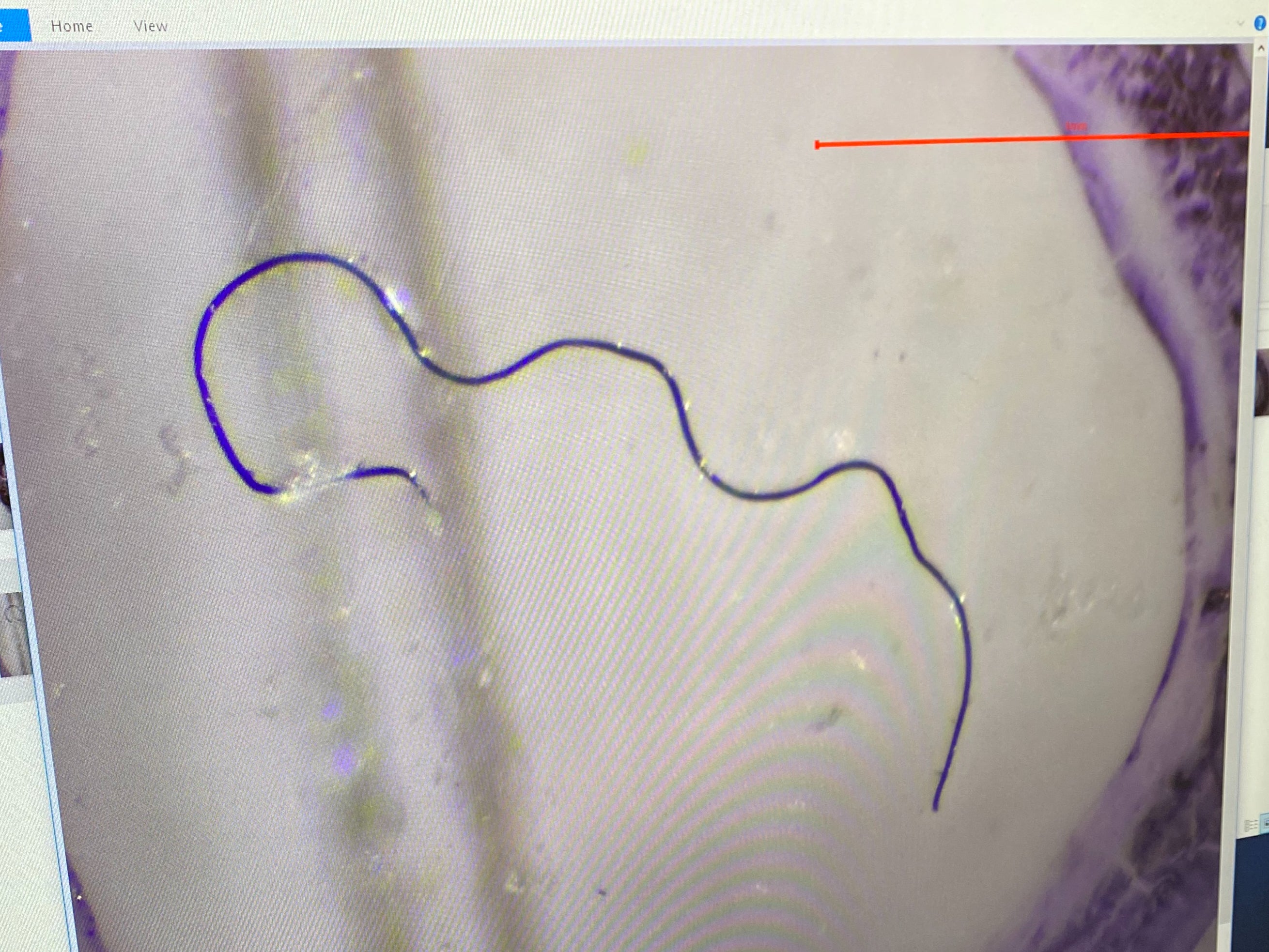

Microplastics – tiny plastic particles less than five millimeters in size – are created when larger plastic products break down. These particles are now found almost everywhere, from the deepest parts of the ocean to the air we breathe. They have been detected in over 1,300 marine species and are part of the food chain, raising concerns about their impact on ecosystems and human health.

The study shows that even if no more plastics were produced, the pollution problem would continue to worsen. According to the researchers, the degradation of existing plastic waste means that microplastic pollution could more than double by 2040.

“Plastic pollution doesn’t really disappear; it just breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces,” Dr Joel Rindelaub from the University of Auckland, said.

“Everywhere we look, we have found plastics, from remote locations across the globe to inside our own bodies. Plastics are here, and they are here to stay,” Dr Rindelaub said.

The review compiles data from studies conducted on microplastic pollution around the world in the last 20 years. These particles are found to be especially prevalent in oceans, where they accumulate in coastal areas and estuaries. Marine species ingest these particles, leading to a range of ecological consequences that could disrupt food chains and ecosystem services.

“The area of ecosystem effects is where we have been working,” says professor Simon Thrush from the University of Auckland, who has spent the past decade studying the impact of microplastics on coastal ecosystems.

“Our research shows that ecosystem effects are apparent at low concentrations, with important consequences for the ecosystem services generated from estuaries and coasts.”

Marine environments, particularly in densely populated areas, are under significant stress from microplastics. Dr Thrush’s findings suggest that these tiny particles, even in small quantities, can alter ecosystem functions, impacting the health of marine life and the benefits these systems provide to humans.

While there is growing awareness of the microplastic problem, the study shows that mitigation efforts have been slow and insufficient. Recycling programmes and plastic bans, though useful, are not enough to tackle the sheer volume of plastic waste already in existence. Current strategies are mostly focused on reducing the production of new plastics, but even this has been difficult to achieve.

“Preventative strategies, like decreasing plastic production, have encountered several challenges,” says Dr Rindelaub. “This highlights the importance of collaborative efforts between industries, governments, and consumers to limit plastic pollution and reduce risk to both humans and the environment.”

The review also shows that there is a need for better tools to detect and assess microplastics. Different methods of studying microplastics have produced varying results, making it difficult to fully understand their toxicity and overall impact.

Dr Sebastian Naeher, a microplastic researcher from GNS Science, said: “We’re improving our estimates, but the problem is growing. The biggest challenges are ahead.”

Research techniques also struggle to account for nanoplastics – particles even smaller than microplastics – that are even more difficult to detect. These tiny particles can infiltrate cells and tissues, raising additional concerns about their effects on health and the environment.

Microplastics are not only an environmental concern but also a growing health issue. The study shows that these particles are present in food and drinking water, and they have even been found in the air. However, the long-term health effects of exposure to microplastics remain unclear.

“There are implications for all aspects of health, including my own area of cancer,” says associate professor George Laking from the University of Auckland.

“The review brings together evidence for a precautionary approach in plastics policy. Use of plastics, including biodegradable and recyclable types, should be kept to a minimum.”

The review stresses that while there is mounting concern over the health risks posed by microplastics, more research is needed to fully understand their potential impacts. For now, experts recommend a cautious approach, advocating for reduced plastic use and better management of plastic waste.

Researchers from University of Plymouth say that addressing the microplastic problem requires more than just scientific research. They argue for a multidisciplinary approach that brings together natural sciences, social sciences, and economics to create comprehensive strategies.

“In our view, science will be just as important guiding the way towards solutions as it has been in identifying the problems,” write the authors.

“The key to stemming the release of plastics and microplastics will be choosing wisely – when is it appropriate or necessary to use plastics, and what are the best strategies to reduce harm?” says professor Sally Gaw from the University of Canterbury.

Dr Gaw said the fight against plastic pollution needs the same kind of efforts seen to eliminate other harmful substances, such as asbestos and organochlorine pesticides, which required global action and sustained policy changes.

Public engagement and awareness are also critical. Despite widespread public concern, the review shows that there has been limited progress in implementing strong regulatory frameworks. International discussions, including the ongoing negotiations on United Nations Global Plastic Pollution Treaty, have yet to result in effective global solutions.

The review concludes that while there have been significant advances in understanding microplastics and their effects, there is still a long way to go. More research is needed to fill the gaps in knowledge, especially regarding the health impacts of microplastics and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Researchers say the focus should shift towards preventing plastic waste at its source. This means stronger regulations, improved recycling infrastructure, and more consumer responsibility. However, they also stress the need for global cooperation and a concerted effort to change how we use and dispose of plastic.

“Plastics are here to stay. But by taking preventative action now, we can at least stop the problem from getting worse,” Dr Rindelaub said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments