Plastic-eating bacteria discovered by student could help solve global pollution crisis

Exclusive: Microbes found near plastic refinery degrade material, turning it into food

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A student may have found a solution to one of the world’s most urgent environmental crises – breeding bacteria capable of “eating” plastic and potentially breaking it down into harmless by-products.

The microbes degrade polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – one of the world’s most common plastics, used in clothing, drinks bottles and food packaging.

It takes centuries to break down, in the meantime doing untold damage to its surroundings.

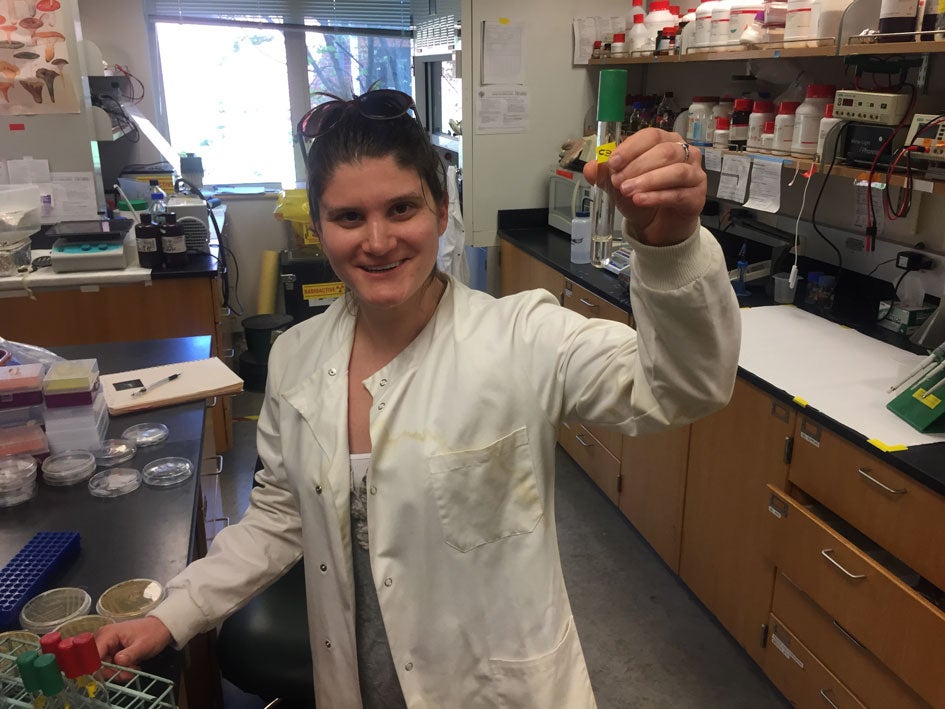

Morgan Vague, who is studying biology at Reed College in Oregon, said the process, if sped up, could play a “big part” of solutions to the planet’s plastic problem, which sees millions of tonnes dumped in landfill and oceans every year.

Around 300 million tonnes of plastic is discarded each year, and only about 10 per cent of it is recycled.

“When I started learning about the statistics about all the plastic waste we have, essentially that told me we have a really serious problem here and we need some way to address it,” Ms Vague told The Independent.

After she began learning about bacterial metabolism and “all the crazy things bacteria can do”, the student decided to find out if there were microbes out there able to degrade “straight-from-the-store” plastic.

She began hunting for microbes adapted to degrade plastic in the soil and water around refineries in her hometown of Houston.

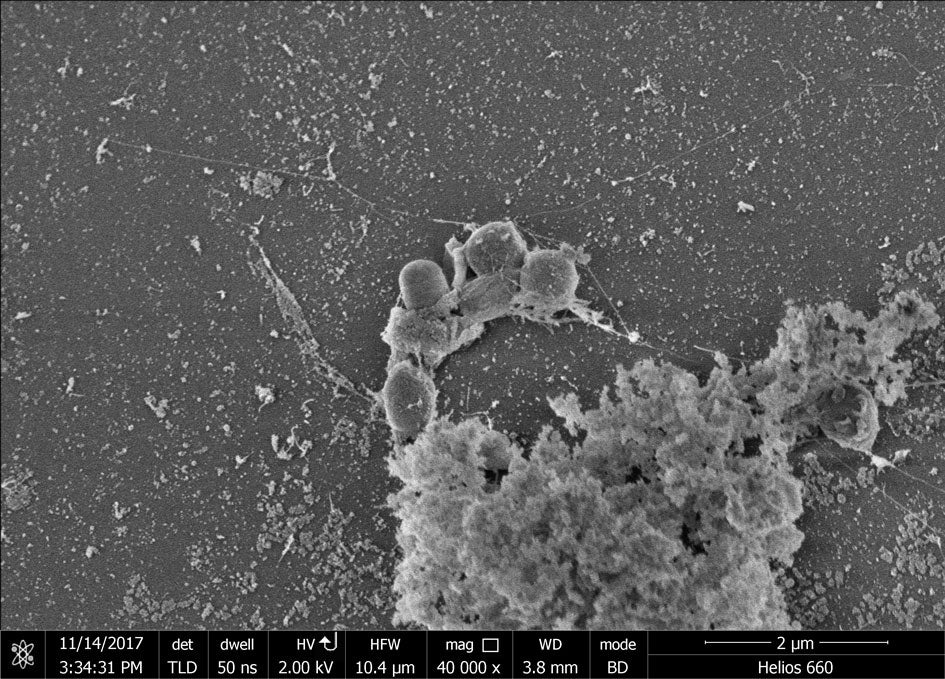

Taking her samples back to college in Portland, Oregon, Ms Vague began testing around 300 strains of bacteria for lipase, a fat-digesting enzyme potentially capable of breaking down plastic and making it palatable for the bacteria.

She identified 20 that produced lipase, and of those three that boasted high levels of the enzyme.

Next she put the three microbes, one of which appears to have been previously undiscovered, on a forced diet of PET she cut from strips of water bottles.

She was stunned to find the bacteria worked to digest the plastic.

“It looks like it breaks it down into harmless by-products that don’t do any environmental damage, so right now what it’s doing is breaking down the hydrocarbons within the plastic, and then the bacteria is able to use that as food and fuel,” she said. “So essentially it’s using that to live. It’s essentially turning plastic into food.”

But she warned there was a “long way to go” until we will start to see the microbes eating plastic at anything like the rate useful in disposing of plastics.

The next step, said Professor Jay Mellies, a microbiologist who supervised Ms Vague’s thesis, is to speed it up, improve pre-treatments on the PET to make it more palatable, and to get the bacteria to work on a variety of plastics.

“The plastic problem is huge and all of us are beginning to be aware of it,” he said. “This is not going to be the total solution, but I think it’s going to be part of the solution.”

Professor John McGeehan, a biologist at the University of Plymouth, who has done research into plastic-degrading enzymes, warned Ms Vague’s research was in its early stages and more testing was needed.

“It’s one of those studies that’s really interesting for sure and they may have found something new, another strain that eats PET,” he said. “It’s simply that it’s early days experiments.”

Earlier this year, Mr McGeehan and colleagues accidentally created a super-powered version of a plastic-eating enzyme, dubbed PETase for its ability to break down PET plastic.

By tweaking the enzyme, produced by a bacteria discovered in a Japanese recycling centre, they were able to make something capable of digesting plastic more effectively than anything previously found in nature.

By breaking down plastic into manageable chunks, researchers suggested their new substance could help recycle millions of tonnes of plastic bottles.

But Professor Mellies insisted their discovery could go even further, and eventually lead to the ability to turn plastics into just spent bacteria and CO2; harmless waste products.

And could their research result in some sort of terrifying super-bacteria capable of multiplying and eating all the world’s plastic?

“People think we’re going to create some sort of Frankenbug and send it out into the environment and all your dashboards and cars are going to digest and go away,” Professor Mellies said.

“That’s not the case. These are naturally occurring bacteria that are out there in the environment and we’re not looking to genetically engineer them, we’re just trying to isolate bacteria and then treat the plastic in a way the bacteria can naturally digest it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments