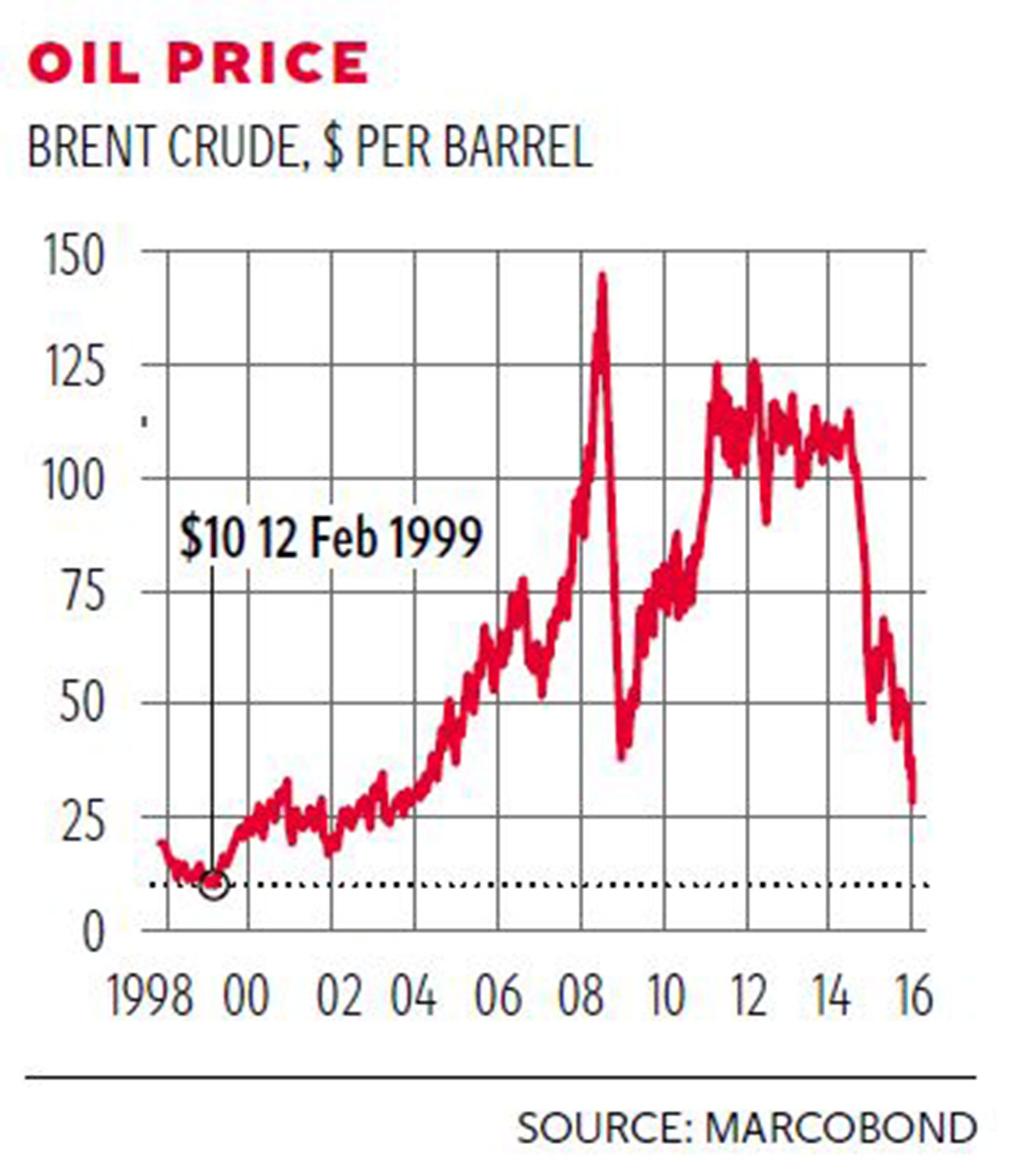

Oil price crash: How the industry's decline will affect the UK economy

With Brent crude reaching a 13-year low, here are the winners and losers from falling oil prices

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The fall in oil prices in the last 18 months has been spectacular, diving from $115 (£80) a barrel in the summer of 2014 to around $28 now.

This extraordinary decline has come about because of rising supply and falling demand, as the revolution in US fracking massively increases global production just as the juggernaut economies of China and Brazil run out of steam.

Nor does the descent show any sign of ending. The lifting of sanctions on Iran on Saturday threatens to push the oil price as low as $10 a barrel, paving the way for the country to become a major oil exporter within months. Here, we look at what $10 oil would mean for the British economy.

North Sea

The diving oil price has already had a devastating effect on the North Sea industry with an estimated 65,000 jobs lost in the past 18 months, many of them in Aberdeen. That’s about 15 per cent of the total UK oil and gas workforce. But the carnage looks set to get even worse as oil companies abandon projects, putting tens of thousands more jobs at risk.

Many of the North Sea’s fields rely on an oil price of $60 a barrel to break even and the lower it goes the more unviable even the cheapest prospects become.

Only last week BP said it would cut a further 4,000 jobs globally – 600 of them in Aberdeen – after the global oil industry dumped 68 projects worth a total of $380bn worldwide last year, including many in the North Sea.

The North Sea’s declining fortunes are also taking their toll on the wider Scottish economy, which is heavily reliant on oil. Tory MSP Murdo Fraser warned yesterday that the oil price slump “represents a serious threat to our economic wellbeing”.

UK economy

The British economy as a whole benefits from low oil prices by reducing what is a major cost for so many industries. Transport becomes much cheaper as fuel costs decrease for cars, lorries, planes and ships, and energy bills decline as oil and gas (which traditionally shadows the oil price) fall.

That’s a significant reduction in two of the biggest costs for many households and businesses. To a lesser extent, falling oil prices also reduce the cost of a wide variety of products because oil is found in everything from combs to heart valves and ink to carpets. So while a slice of the economy gets hammered hard by falling oil prices, the vast majority benefit from falling costs and rising profits.

Renewable energy industry

It’s further bad news for Britain’s green energy sector, which is already reeling after dramatic cuts to subsidy support for solar power and onshore wind.

The sector is still unable to stand on its own two feet without subsidy. The oil price slump – which looks set to continue for years – makes thing worse because it makes oil, and therefore gas, a more attractive electricity source for power stations while solar, wind and hydro become less attractive. This is a particular blow when you consider that before the oil price slump, the green energy sector had been banking on a sharp rise in hydrocarbon prices, rather than an acute decline.

Petrol prices

The pump price has already fallen from 131p a litre when the oil slump began in the summer of 2014 to just below £1 in the cheapest outlets – the supermarket forecourts.

And while the huge tax on fuel means the petrol price can only fall so far and fast, analysts are forecasting we could see a litre going for just 86p if oil dips to $10. That’s the same pump price as we saw back in 1998, when oil was last at $10.

Pensions

Britain’s pensioners will take a big hit because their fortunes are so tied up with those of the oil companies. Pensions are heavily invested in oil companies, which have been seen as stable investments and have traditionally paid out a large annual dividend to their shareholders – many of which are pension funds investing your pensions.

BP’s dividends, for example, are so big that they have traditionally accounted for £1 in every £6 of the total shareholder payouts made by the country’s 100 biggest companies. It’s shares have fallen 35 per cent since the start of the oil price slump, while Shell’s are down 45 per cent.

Banks – which make up another huge chunk in the average pension – are also at risk from the falling oil prices, which have greatly increased the chance of default on the loans they have made to finance exploration of new fields in recent years.

The declining share prices of the banks and oil companies will be partially offset by improving fortunes elsewhere in the economy as their costs come down. But only partially.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments