North Dakota pipeline: How it favours white community over native neighbours - in one map

Officials in North Dakota are tying to force protesters from the site

When cartographer Carl Sack tried to visit the protest site at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, he all but got lost.

The official maps of the area were inadequate - both to show the route, and to reveal the pressing threat to the tribe’s water source that the North Dakota Access Pipeline presented. He decided to create his own.

“I felt called upon to do something, but I was not sure what to do,” Mr Sack, a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told The Independent. “I have the cartography skills, so I decided on the map.”

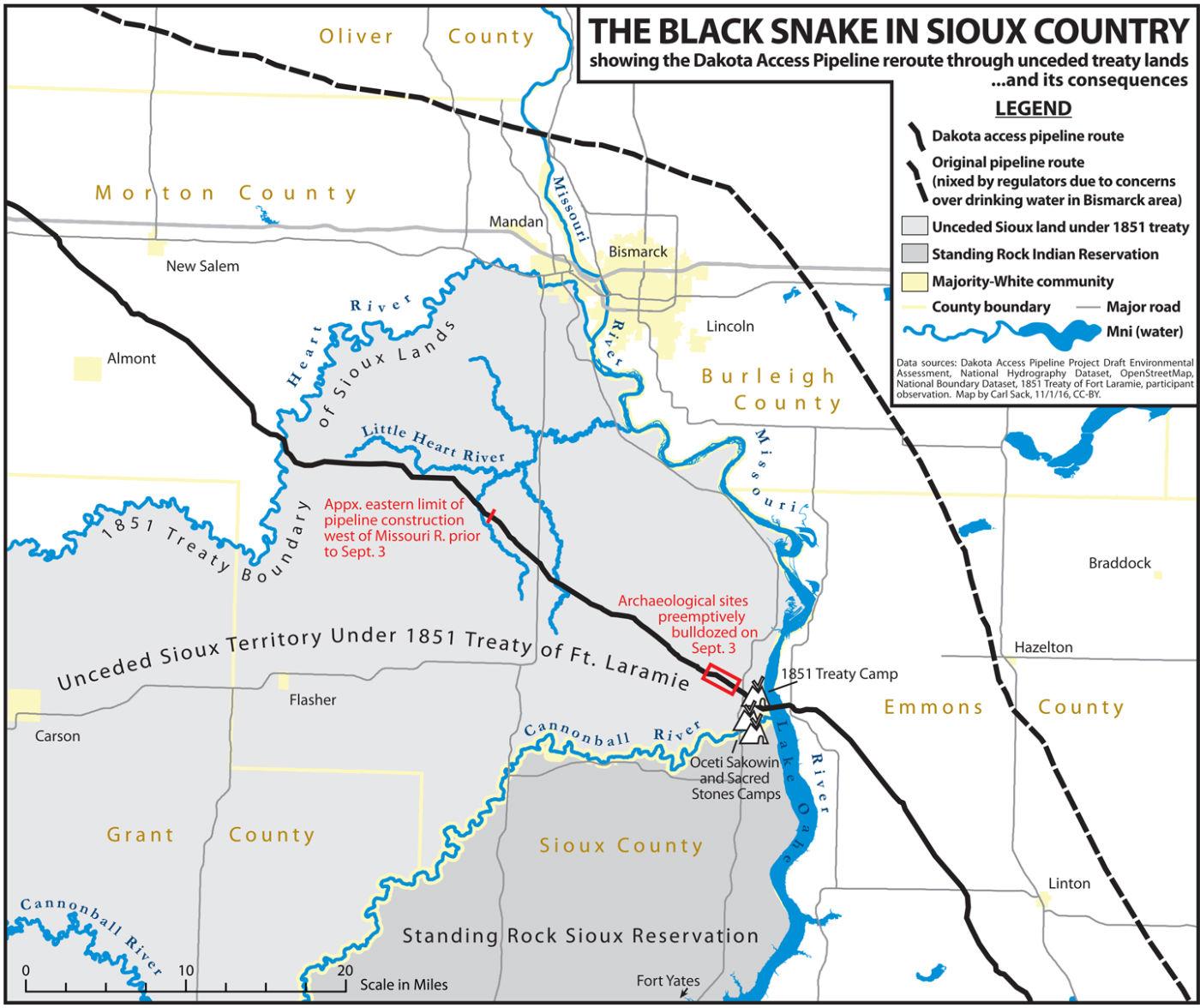

The map the 32-year-old created reveals in stark detail how the proposed route for the pipeline, which stretches for 1,134 miles and transfers oil from the Bakken fields in northwest North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois, was switched after complaints from residents in the overwhelmingly white town of Bismarck, the state capital.

It shows too, how the underground pipeline, which was supposed to be completed by January 2017, passes under the Missouri River at a point very close to the Standing Rock Reservation. Indigenous Americans and activists are concerned that a breach in the pipe could irreversibly pollute the river and harm sacred cultural lands and tribal burial grounds.

“I hope the map gives a good sense of what is at stake here for the Sioux and how they are being discriminated against in favour of the white community,” he said.

Mr Sack wrote a blogpost about the inadequacy of the maps that were available and the false picture they created. The post was republished by Huffington Post.

“It doesn’t tell you that all of Turtle Island (North America) is Indian Country, or that the project runs headlong into international treaties signed between the US and various tribes and then unilaterally violated by Congress,” he wrote.

“It doesn’t show you where the frontline communities have set up camp to fight back….or where the pipeline company, spurred on by the internal pressure of their $3.8bn investment, has bulldozed sacred ground, or where exactly a pipeline break would endanger the drinking water of millions downstream.”

Activists have spent months protesting plans to route the pipeline beneath the lake near the reservation. Reuters said that on Tuesday, North Dakota officials moved to block supplies from reaching the protesters by threatening to use hefty fines to keep demonstrators from receiving food, building materials and even portable bathrooms.

State officials said they would fine anyone bringing prohibited items into the main protest camp following Governor Jack Dalrymple’s “emergency evacuation” order on Monday. Earlier, officials had warned of a physical blockade, but the governor’s office backed away.

The pipeline project, owned by Texas-based Energy Transfer Partners LP, is mostly completed except for the segment planned to run under Lake Oahe, a reservoir formed by a dam on the Missouri River.

Thousands of people are protesting at camps located on US Army Corps of Engineers land, north of the Cannonball River in Cannon Ball. The main protest camp near Cannon Ball is called Oceti Sakowin, the original name of the Sioux, meaning Seven Council Fires.

Protest leaders said state officials and local law enforcement officers were bullying demonstrators with the threat of fines.

“It’s bogus and I don't know about the legality of it,” Kandi Mossett, an organiser with the Indigenous Environmental Network, told Reuters.

“We’re not afraid. We’re moving in and out of the camp at will. So people shouldn’t be afraid of coming and supporting the water protectors. They’ve been bullying us since day one.”

Mr Sack, the graduate student, said he was inspired to use maps as a vehicle for justice by other cartographers, including William Bunge and Zoltan Grossman. Mr Bunge believed maps could help push social change in inner city America.

Both he and Mr Grossman taught at the University of Madison-Wisconsin. In his blog post, about his visit to the site, he quoted Mr Grossman, who once wrote: “The side with the best maps wins."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks