Mysterious human ‘love hormone’ turns starfish stomachs inside out, study finds

Oxytocin is an ancient hormone that makes mice lose their appetite and birds more generous

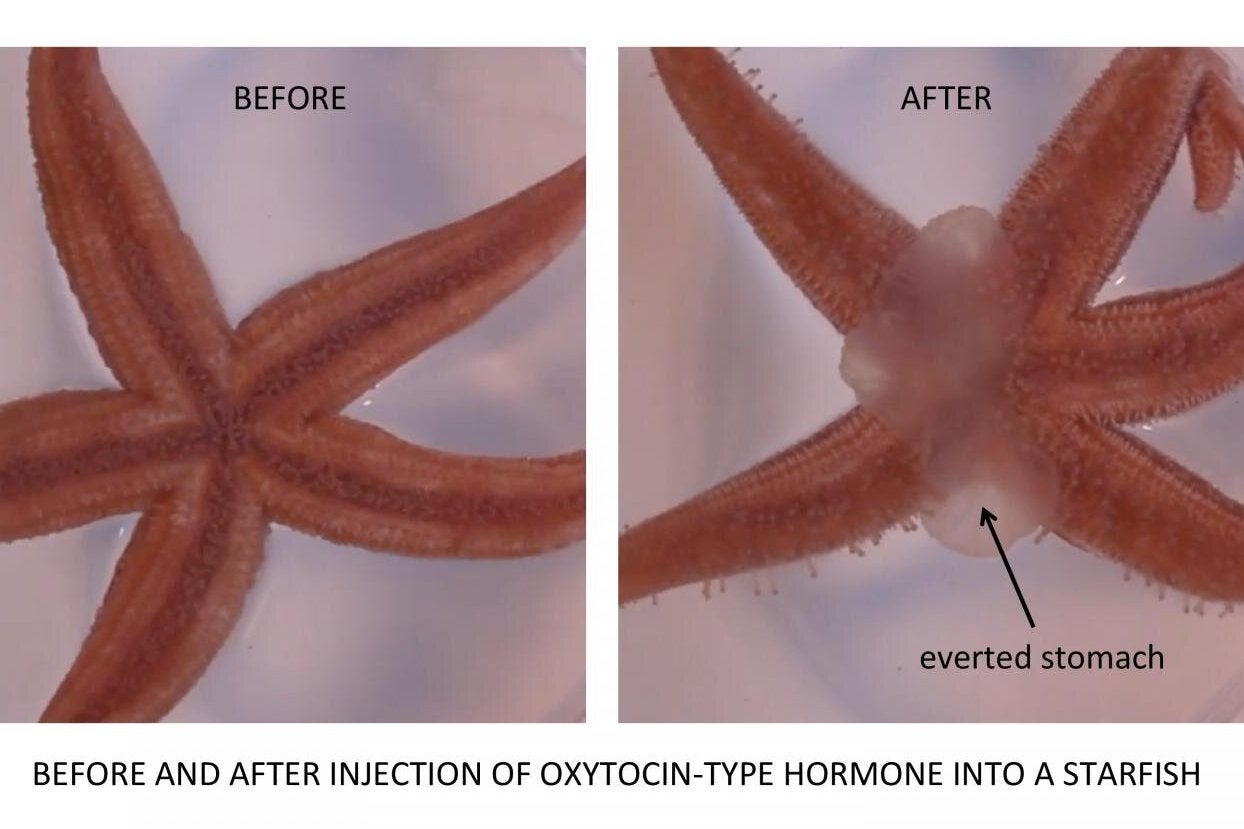

The mysterious “love hormone” released in humans when they fall head over heels for someone causes starfish to turn their stomachs inside out, scientists have discovered.

Oxytocin is an ancient hormone that has different functions across species – previous studies have shown it makes mice lose their appetite and makes some birds more generous.

In the latest research, scientists injected the chemical into starfish and found it triggered their mechanism of “everting” – turning out their stomachs in the posture they use for eating.

Researchers from Queen Mary University of London said the experiment could help control the feeding patterns of the starfish species called the crown of thorns. This species feeds on coral and has “a devastating impact” on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Lead author Professor Maurice Elphick said: “Our study has provided important new evidence that oxytocin-type molecules are important and ancient regulators of feeding in animals.

“So oxytocin is much more than a ‘love hormone’ – perhaps especially for animals like starfish that don’t fall in love."

Dr Esther Odekunle, formerly a PhD student at the university, added: “This research may provide a basis for the development of novel chemical methods to control their appetite for coral.”

Oxytocin-type molecules have been acting in the nervous systems of animals for more than half a billion years.

In humans, oxytocin molecules bind with receptors in the brain and in doing so influence maternal care, social interactions and stress and anxiety levels. The hormone has also been suggested as a treatment for anxiety, depression, addiction, anorexia and schizophrenia owing to its ability to promote social and bonding behaviour.

Starfish were injected with the hormone and within a few minutes started bending their arms and adopted a “humped” posture, similar to that used when feeding – and the stomach was then everted from the mouth.

The animals feed by climbing onto shellfish and adopting this posture, then using the tiny tube feet under their arms to pull apart the two valves of their prey.

The starfish then evert their stomach into the gap they have created, before digesting the soft tissues into a soup-like mixture and drawing this back into their body to eat, according to the study published in the journal BMC Biology.

Professor Elphick said: “What is fascinating is that injecting the hormone in starfish induces what is known as fictive feeding. The starfish are behaving as if they are feeding on a mussel or an oyster but no mussel or oyster is there to be eaten.”

The researchers also found the effect of oxytocin was so powerful it made starfish two to three times slower at righting themselves when flipped over – an important defence mechanism when they are upturned by strong waves.

They also found that the hormone exists naturally in regions of the starfish body – including the central nervous system and the stomach – and its effects appeared to be consistent with the oxytocin-type molecules.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks