'Killer whale apocalypse': Banned chemical pollutants could wipe out species, study finds

Seas around UK are some of world's most polluted, researchers say

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Toxic chemical pollutants could trigger a “killer whale apocalypse” with the species likely to disappear entirely from parts of the world’s oceans within just a few decades, conservationists have warned.

More than 40 years after PCBs – or polychlorinated biphenyls – were banned, experts said they were still posing a deadly threat to orcas in the wild.

And the seas around the UK are some of the most polluted in the world, researchers from Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Aarhus University found.

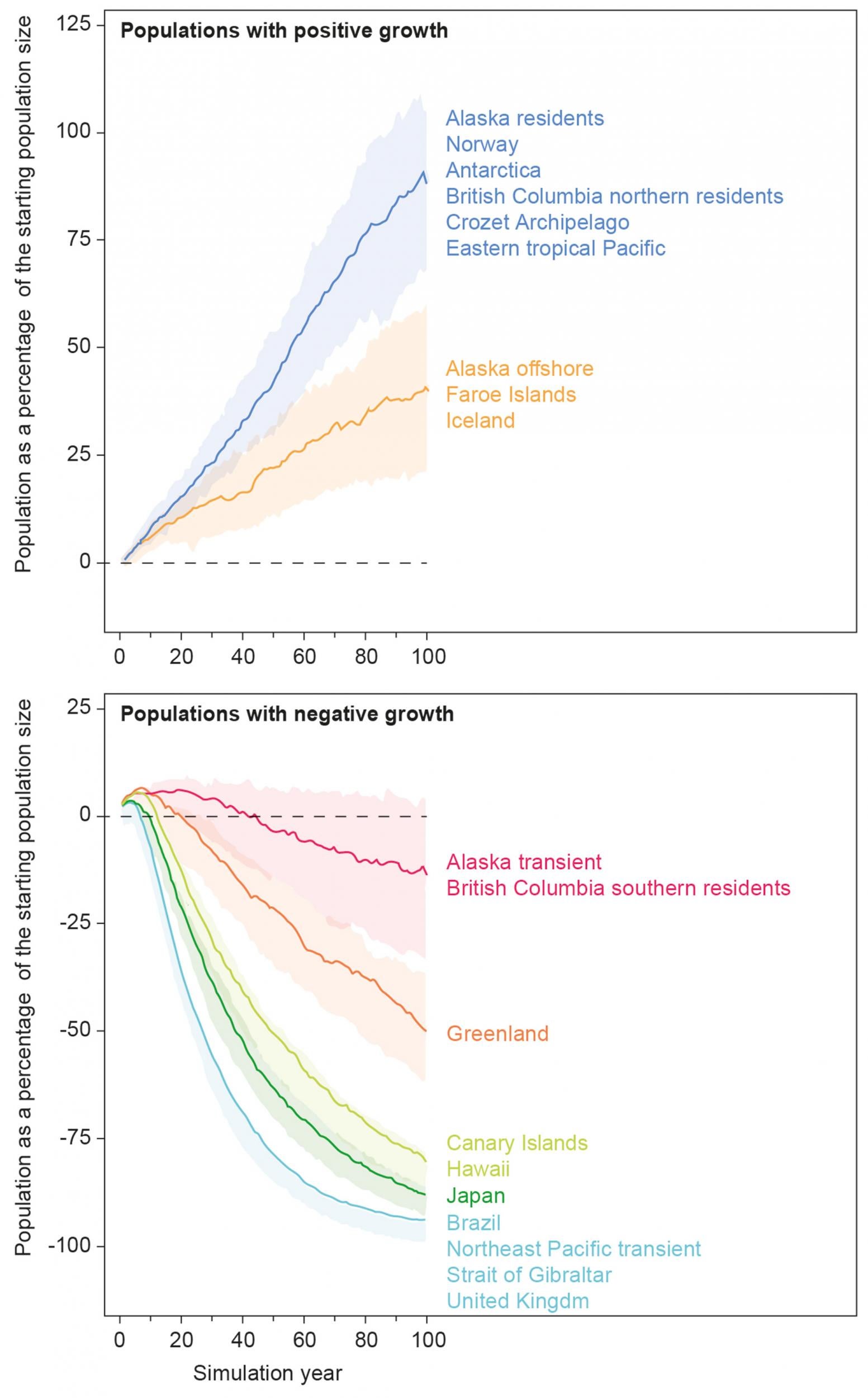

They recorded rapidly declining populations of killer whales in 10 of the 19 areas investigated, with the species expected to disappear entirely from several areas within a few decades.

ZSL conservationists said the pollutants threatened to “wipe out” the species in a “killer whale apocalypse”.

In the UK, numbers of orcas and dolphins have plummeted, with the killer whale population off the coast of Scotland down to just eight.

Dr Paul Jepson, co-author of the study from ZSL’s Institute of Zoology, said the PCB problem in Europe was “about as bad as it could possibly get”.

“All we have done is banned them and hoped they went away,” he told The Independent. “The US produced even more PCBs but they are spending a lot of money on a clean-up and it is working.”

Asked if this was the beginning of the end for world’s orca population, Dr Jepson replied: “No, it is worse than that. The beginning of the end for killer whales began in the 1960s when high levels of PCBs were being used.”

The killer whale is one of the most widespread mammals on Earth and is found in all of the world’s oceans, from pole to pole. But today, only the populations living in the least polluted areas possess a large number of individuals.

The seas around the UK and the Strait of Gibraltar, as well as off the coast of Brazil and in the northeast Pacific, are among the worst affected, where models show the populations have virtually been halved during the half century since PCBs have been present.

One of the UK’s last killer whales, named Lulu, died in 2016 after becoming tangled in netting. But a post mortem found she was contaminated with “shocking” levels of PCB.

Dr Andrew Brownlow, head of the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme, warned last year that she was “one of the most contaminated animals on the planet in terms of PCB burden and does raise serious questions for the long-term survivability of this group”.

The chemical pollutants can have a dramatic effect on the reproduction and immune systems of killer whales and affect that species most acutely as they form the last link in a long food chain.

Killer whales, whose diet includes seals, tuna and sharks, had the highest PCB concentrations and it is these populations that are at the highest risk of population collapse, the study found. Killer whales that primarily feed on small-sized fish such as herring and mackerel had a significantly lower content of PCBs.

The chemical pollutants are passed from the adult orca to its offspring in the mother’s milk, which means the hazardous substances remain in the bodies of the animals instead of being released into the environment where they eventually degrade.

Researchers measured values as high as 1,300 milligrams per kilo in the blubber of killer whales. For comparison, a large number of previous studies have shown that animals with PCB levels as low as 50 milligrams per kilo of tissue may show signs of infertility and severe impacts on the immune system.

Overfishing and man-made noise have also contributed to declining numbers.

Aarhus University’s Jean-Pierre Desforges, who led the investigations, said over half of the studied killer whale populations around the globe were “severely affected” by PCBs.

The chemicals have been used around the world since the 1930s, with more than a million tonnes produced and used in a variety of products including electrical components and plastics.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, PCBs were banned in several countries and in 2004, through the Stockholm Convention, more than 90 countries committed to phase out and dispose of PCB stocks.

Their damaging impact has been recorded in other animals, including polar bears, whose reproductive organs were found to become deformed by the chemicals.

However, in the oceans around the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Alaska and the Antarctic, the prospects are not so gloomy, the researchers found.

Here, killer whale populations are increasing and conservationists predict they will continue to do so throughout the next century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments