It holds enough water to raise sea levels 50 metres, but East Antarctica ice sheet is even more unstable than we thought

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The massive ice sheet of East Antarctica, which is up to 4 kilometres thick and holds enough frozen water to raise sea levels by more than 50 metres, is more unstable than previous studies have suggested, scientists said.

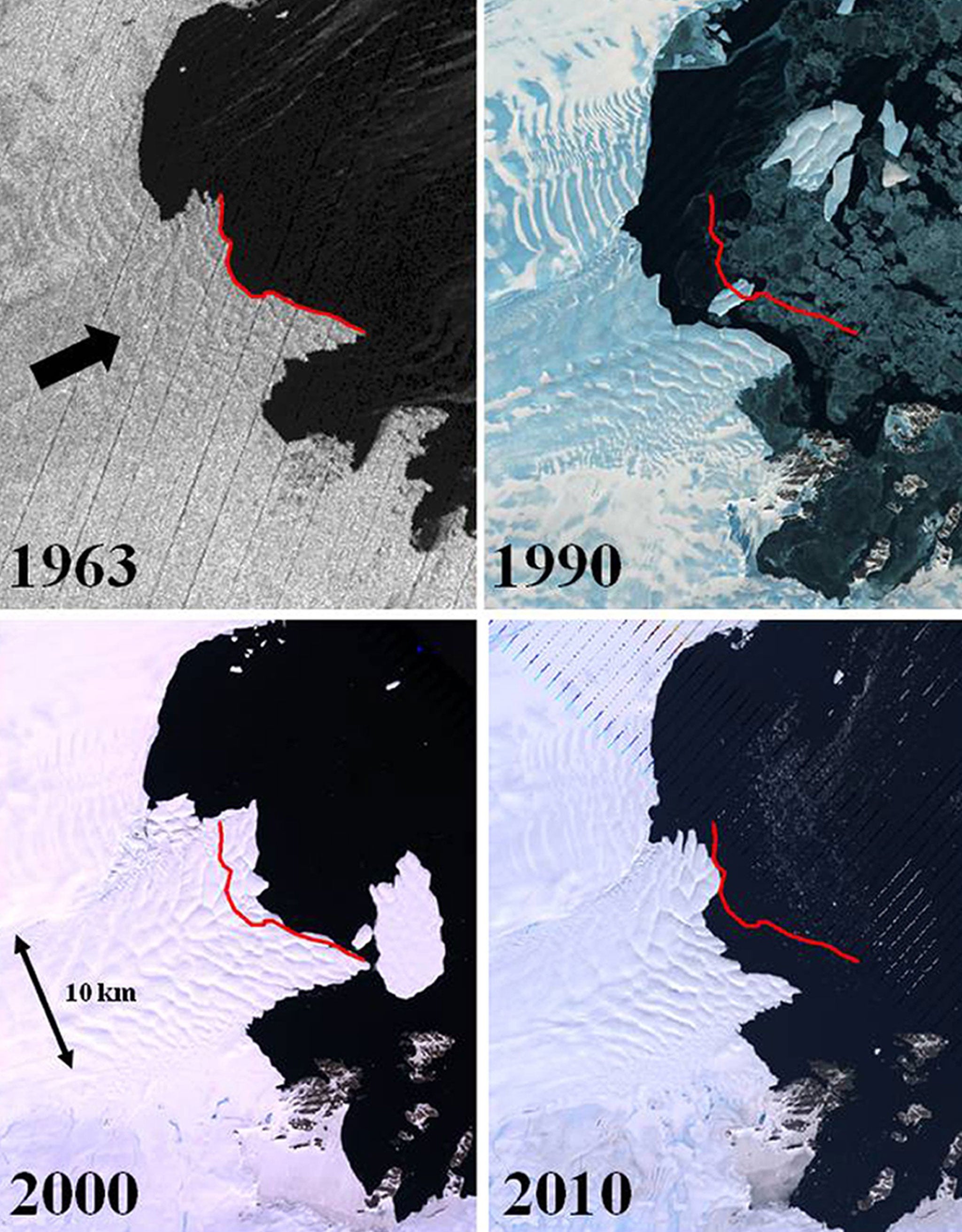

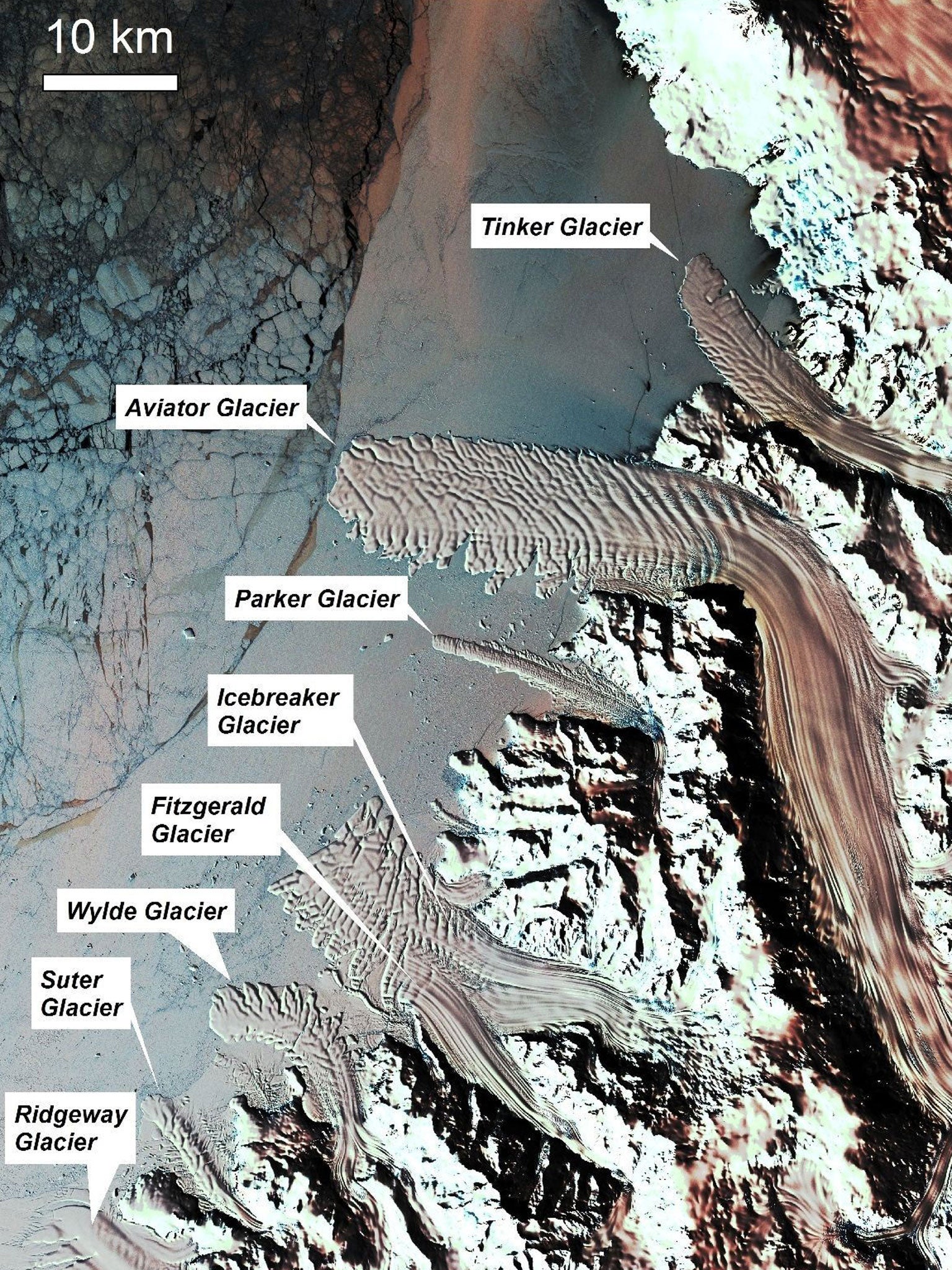

Declassified images from spy satellites going back 50 years have revealed that the coastal glaciers and floating sea ice of Antarctica are more susceptible to air and sea temperatures than previously supposed, the researchers found.

The images, which cover thousands of miles of East Antarctic's coastline and include measurements of 175 glaciers, show there is rapid and synchronised melting and freezing when local temperatures increase or fall, according to the study published in Nature.

"We know that these large glaciers undergo cycles of advance and retreat that are triggered by large icebergs breaking off at the terminus, but this can happen independently from climate change," said Chris Stokes of Durham University, who led the study.

"It was a big surprise therefore to see rapid and synchronous changes in advance and retreat, but it made perfect sense when we looked at the climate and sea-ice data. When it was warm and the sea-ice decreased, most glaciers retreated, but when it was cooler and the sea ice increased, the glaciers advanced," Dr Stokes said

Melting sea ice and glaciers could affect the speed at which the ice sheet on the land melts and falls into the sea. "In many ways, these measurements of terminus change are like canaries in a mine - they don't give us all the information we would like, but they are worth taking notice of," he said.

Climate scientists have focussed on the ice sheets of the West Antarctic and Greenland because these were thought to be the less stable then the much bigger ice sheet of East Antarctica, which sits on a mountain range and is much colder than other ice sheets.

Dr Stokes said: "If the climate is going to warm in the future, our study shows that large parts of the margins of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet are vulnerable to the kinds of changes that are worrying us in Greenland and West Antarctica - acceleration, thinning and retreat."

He added: "We need to monitor their behaviour more closely and maybe reassess our rather conservative predictions of future ice sheet dynamics in East Antarctica."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments