Is this the end of the Holocene period?

The Romantics first wrote about a time full of flora and fauna, but after a volcani eruption they became concerned with a possible human extinction and the end of the geological era

The idea that we are now living in the Anthropocene – a new geological epoch characterised by humanity’s influence on the planet – has gained wide currency in recent years. And now a group of experts tasked by the International Commission on Stratigraphy to assess whether human activities are leaving a strong trace in the rock record have advised that the Holocene – the epoch that has defined the last 10,000 years – should indeed be declared over.

To say that we are living in the Anthropocene does not mean that our impacts now define the earth system, or that we have control over it. Rather, it means that our activities play an increasingly important role within a complex set of interactions with a wide range of other forces, objects, and agencies.

For some commentators, the Anthropocene marks a breach from the past that requires new ways of thinking. And yet, for at least two centuries, nature writers have been addressing the complexity of humanity’s entanglements with the natural world.

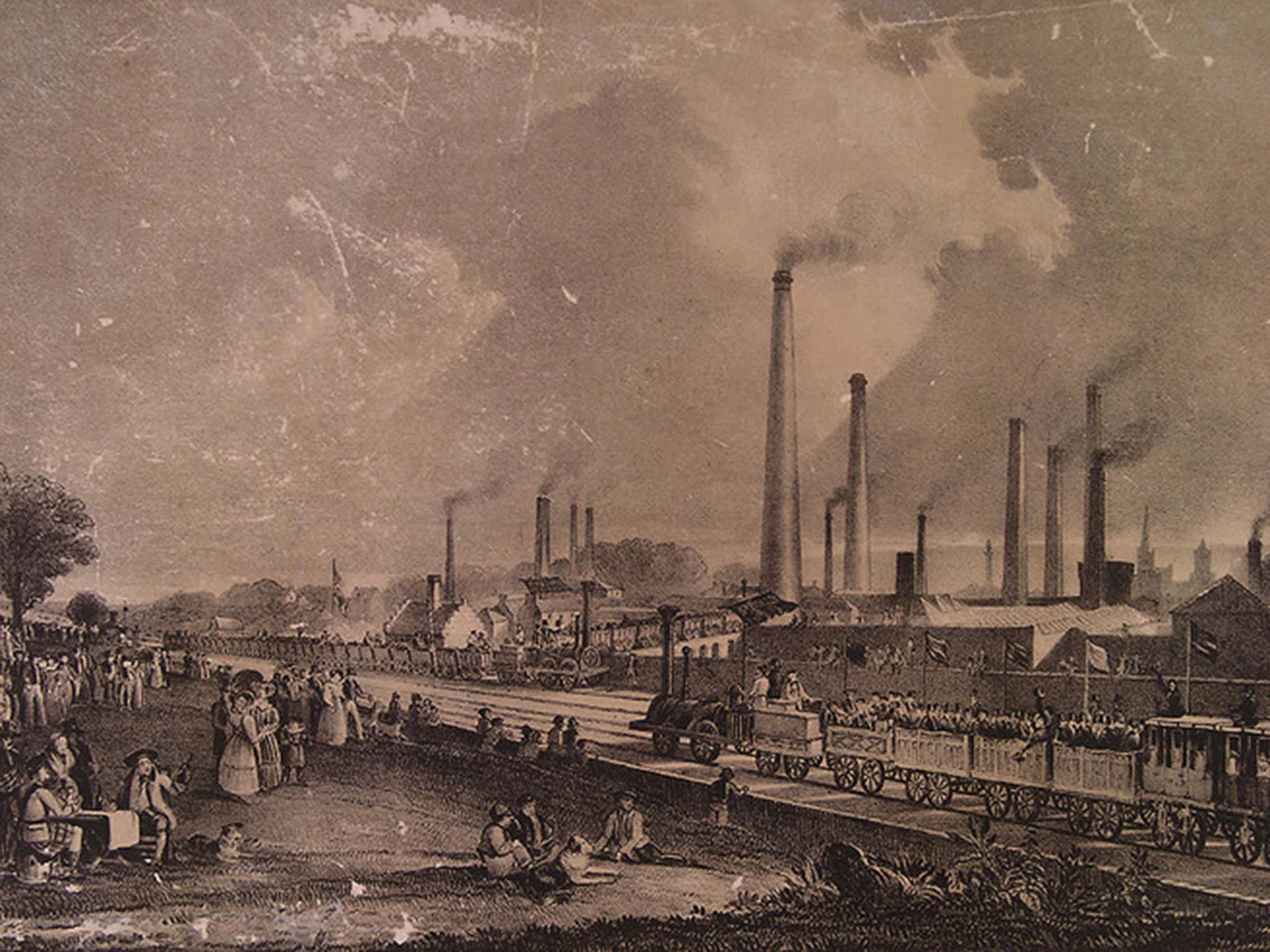

One plausible start date for the Anthropocene is during the Romantic period (1780-1830), which saw the beginning of the world’s industrialisation and of the increasing atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming. Coincidentally or not, the same period also saw a remarkable flowering of literature concerned with the relationship between human beings and nature.

Authors such as Gilbert White, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Charlotte Smith, and John Clare wrote about their local flora, fauna, and natural phenomena with unprecedented depth and richness, thereby inventing the modern genre of nature writing.

Their works also bear the imprint of global environmental forces. The final pages of White’s The Natural History of Selborne (1789), for example, describe “the horrible phaenomena” of the summer of 1783, including a “peculiar haze, or smokey fog” that appeared across Europe and created a “superstitious kind of dread”. And the poet William Cowper wrote of the same summer that:

the props

And pillars of our planet seem to fail,

And nature with a dim and sickly eye

To wait the close of all.

The principal cause of the unusual conditions of 1783 was the eruption of the Laki volcano in Iceland. A generation later, the much larger eruption of the Indonesian volcano Mount Tambora in 1815 was to have a defining impact: both on the climate, and on Romantic literature.

The year without a summer

The following year, 1816, was exceptionally cold and wet and came to be known as the “year without a summer”. What Samuel Taylor Coleridge called “this end of the World Weather” led to incidences of famine, political unrest, and disease across the globe.

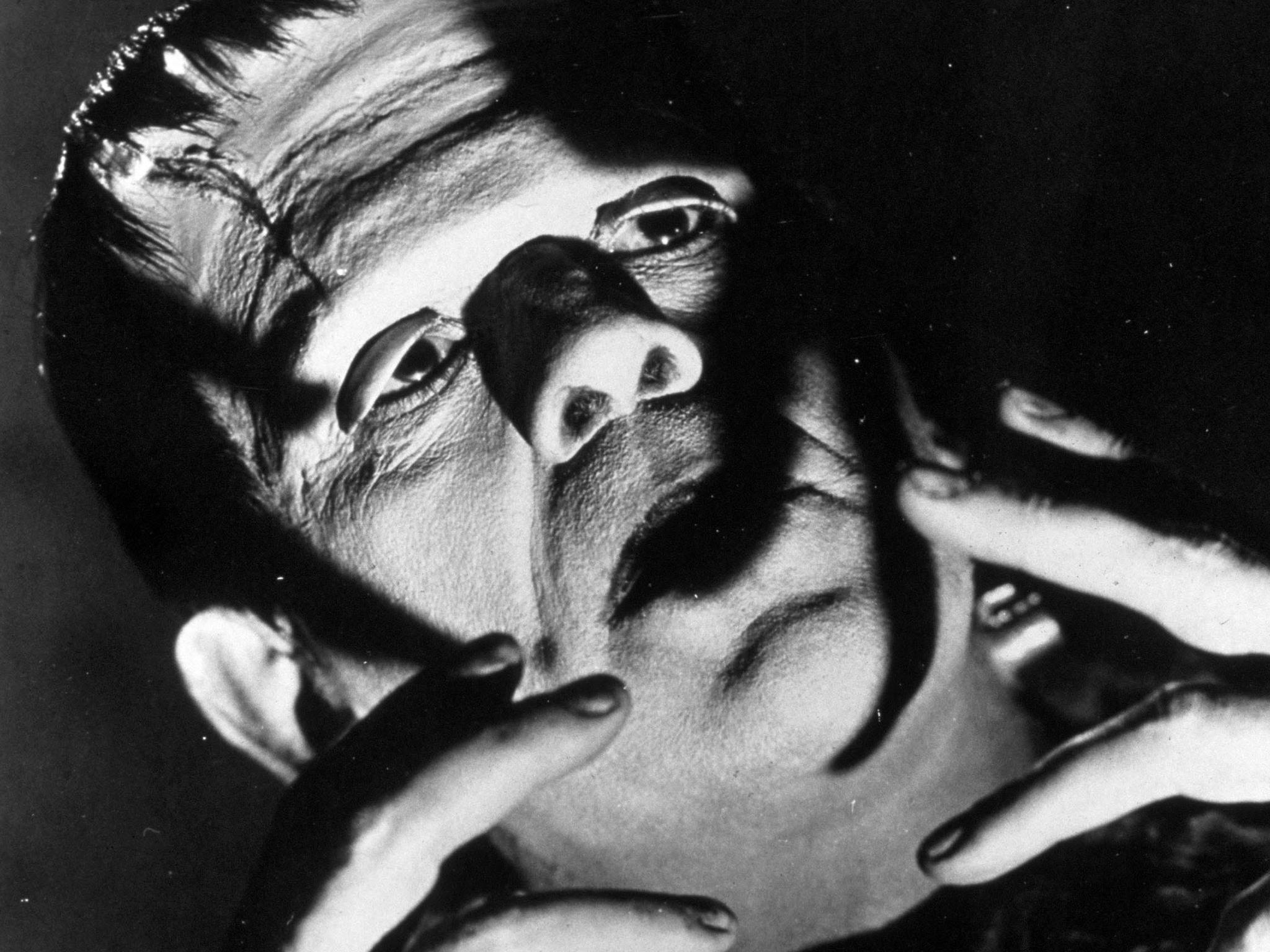

The summer of 1816 is also known as one of the most productive periods in the history of English literature. This is not least because it saw the conception of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well as major works by her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley and their friend Lord Byron. All were composed during the time that the three spent together near Geneva.

A mixture of terrible weather, the sublime Alpine landscapes that they visited, and their interest in science led them to think hard about the vulnerability of human communities living with uncontrollable natural forces. They even considered the possibility of human extinction.

A key concern for Byron and the Shelleys was global cooling. Responding to contemporary geological theories (and no doubt the unnaturally cold temperature), Percy Shelley argued that the glaciers around Mont Blanc were continually “augmenting”. In a letter to his friend Thomas Love Peacock, he raised the possibility that “this globe which we inhabit will at some future period be changed into a mass of frost by the encroachments of the polar ice”. And his poem “Mont Blanc” describes glaciers that “creep | Like snakes that watch their prey”; a “flood of ruin” that threatens human existence.

Byron goes further in his poem “Darkness”, imagining the dimming of the entire universe: “The icy earth | Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air.” In a chillingly apocalyptic vision, the growing cold and darkness leads to resource wars, ecosystem collapse, famine, and eventually the destruction of all life on Earth, leaving it “a lump of death”.

The extinction of the human species is also addressed in Frankenstein and here again it is linked to global cooling. Victor eventually destroys his work on the Creature’s companion due to his fear that the two might procreate and supplant humanity. Significantly, the Creature is much better adapted to cold conditions than his creator. Frankenstein raises the spectre of a post-human future in which a stronger species develops that is able to flourish on an icy globe.

Cold futures

The anxieties of Romantic writers might seem rather different to ours. Despite their interest in climate – including the possibility that human activity could “improve” it – they were not concerned by the possibility of a human-made global climate crisis. But given that some scientists are proposing to counteract the effects of climate change by mimicking the effects of a large volcanic eruption, their writing seems particularly pertinent to the Anthropocene.

Their works do not offer simplistic solutions. Frankenstein is not a warning against technological experimentation. Nor is it an endorsement of the idea that we should “love our monsters” and therefore embrace geoengineering.

The most interesting Romantic literature is not so much concerned with what we “do” to nature or vice versa, but with the entanglement of human and nonhuman agents. Thus the protagonist of Byron’s drama Manfred refuses to bow down to the personified elemental forces that surround him and yet relies on their power. And “Mont Blanc” raises the possibility that reality is defined by the human imagination at the same time as presenting our vulnerability to environmental change.

A key legacy of Romanticism has been a form of nature writing that depicts the solitary individual’s transcendent experience of the sublime landscape. Perhaps unfairly, such writing has sometimes been criticised for its self-absorption and blindness to larger contexts.

But a richer understanding of Romantic literature might inform a nature writing fit for our current situation: messy, urgent, aware that “nature” does not exist separately from politics and economics, and reflective of the complex human-nonhuman assemblages that characterise the Anthropocene.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation (theconversation.com). David Higgins is an Associate Professor in English Literature, University of Leeds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks