How we discovered the world’s largest tropical peatland, deep in the jungles of Congo

A swampy area the size of England stores as much carbon as 20 years of US fossil fuel emissions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

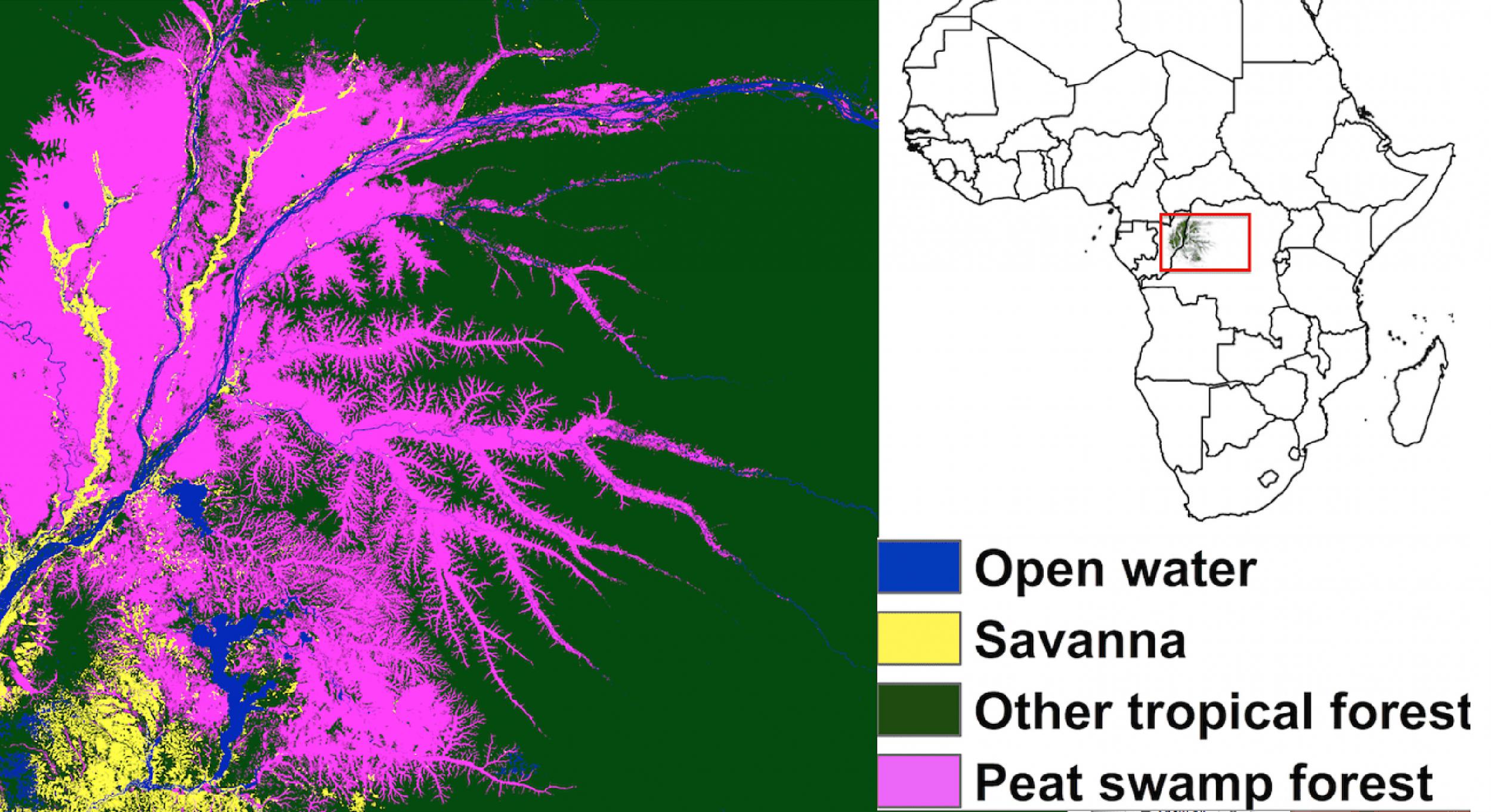

Your support makes all the difference.In the geographical heart of Africa lies a huge wetland. After years of exploring these remote swamps, our research shows that the region contains the most extensive tropical peatland on Earth.

Astonishingly, 145,500 sq km of peatland – an area larger than England – went undetected on our crowded planet until now. We found 30 billion metric tonnes of carbon stored in this new ecosystem that nobody knew existed. That’s equivalent to 20 years of current US fossil fuel emissions. Here we describe how we did it, and our struggles against sabotage, arrest, and losing our own minds.

Peat is usually associated with cold places, not the middle of the hot, humid, Congo Basin. It’s an organic wetland soil made of partially decomposed plant debris. In waterlogged places those plants can’t entirely decompose, and are not respired as carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The peat thus builds up slowly, locking up ever-more carbon. The amounts involved are huge: peat covers just 3 per cent of Earth’s land surface, but stores one-third of soil carbon.

We knew that peat can be formed under some tropical swamp forests. Might the world’s second largest tropical wetland, known as the Cuvette Centrale, overlie peat?

After the eureka moment of asking the right question, we searched to see if somebody else already knew the answer. About once a decade since the 1950s some obscure report would mention in passing that there was peat in the Congo Basin. Not one gave a grid reference, village or river to locate it. It was important to confirm whether it was present, though, as peatlands in southeast Asia have been targeted for palm oil and other industrial agricultural projects, leading to huge carbon emissions and catastrophic wildlife losses. Palm oil is now on the march in Africa.

For our Congo search, we had nothing to go on. Given the Congo Basin is slightly larger than India, it is not practical to just turn up and begin your search on foot. To pinpoint where to go, we combined data from different satellites to identify year-round waterlogged areas with the right sort of plants. In 2012, with researchers from Congo and UK universities plus NGO Wildlife Conservation Society, we began to look for peat in northern Republic of Congo.

Life in the swamps

No one was really prepared for the reality of life in the swamps. The forest is quite open, which increases the equatorial heat, but humidity is still 100 per cent which makes it extremely sweaty. Your feet are wet and your new world is filled with insects.

Walking through the swamps is only possible in the dry season. Wading is the mode of transport at all other times. But then when it is dry, there isn’t any free-flowing water. We often had to filter drinking water from the pits that crocodiles excavate and live in. Dry land and water kept us leashed near the edges of the swamp. But, happily we found some peat.

There were various hiccups. The team allegedly did not have the right papers, and was put under “town arrest”, confined to the provincial capital Impfondo. A week in and still no movement, but a friendly BBC journalist asked if the government had any comment on the arrested UK student. The next day everyone was free.

On another occasion, a curious panther unearthed and broke our instrument measuring the water table. But, as the work progressed, we learned more and more about the swamp from the local villagers who made the expeditions possible. We would see elephant feet and gorilla hands imprinted in the peat. We were increasingly in awe that a remote, almost unknown, wilderness such as this could still be found on Earth today.

Into the wild

We were then able to undertake our biggest expedition yet: a 30km walk to the centre of what we suspected was one of the largest single areas of peatland in the region.

In February 2014, our team of three scientists and five assistants from local village Itanga, with the blessing of their chief and elders, began its trek to the middle of the swamp. With all our food and equipment on our backs, the days were spent advancing our way through (or sinking into) the forested swamp, sampling the peat and overlying vegetation every 250 metres, then doubling back to pick up more food and equipment.

In the evenings, we made wooden platforms, on which we could pitch freestanding mountaineering tents. We washed in one of the many muddy pools of water on offer. The team would then sit round the fire – on a platform, to be out of the water – and enjoy a meal of cassava and smoked-dry fish.

After 17 days, covering just 1.5km a day, we finally reached the centre of the swamp between two of the major rivers. Our reward was not only the knowledge that these peatlands are indeed vast. We also found ever-deeper peat, reaching up to 5.9m, roughly the height of a two-storey building.

Yet being in such a remote location was mentally disconcerting. We knew that tree roots would always stop us sinking into the peat up to our necks. And we knew that the rain in a single torrential storm was not enough to flood the swamp and erase our path out. But our senses informed our brains that this was a dangerous place. Days later, wading the last river, we appeared blinking into the bright sunlight of the savanna, all eight of us sank to our knees, elated to have survived.

A carbon reservoir

Our field measurements revealed that just two specific forest types have peat underneath: a year-round waterlogged swamp of hardwood trees and a year-round waterlogged swamp dominated by one species of palm. We then used satellite data to map these two specific peat swamp forests to determine the boundaries of the Congo Basin peatlands. Combining this area with peat depth and peat carbon content from our laboratory analyses allowed us to calculate that just 4% of the Congo Basin is peatland, but it stores as much carbon below ground as that stored above ground in all the trees of the other 96%.

And now what? In policy terms, while the area is not under immediate threat, it needs protecting: as well as being critical habitat for gorillas and forest elephants, the Congo peatlands are only a carbon-rich resource in the fight against climate change when left intact.

The good news is that the Republic of Congo government is considering extending the area of protected swamp by expanding the Lac Tele Community Reserve by up to 50,000 square kilometres. And for us scientists? Now we know that this vast new ecosystem exists, we’d like to know how it works.

Simon Lewis is professor of global change science at the University of Leeds and UCL; Greta Dargie is postdoctoral researcher in tropicalpPeatlands at the University of Leeds. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments