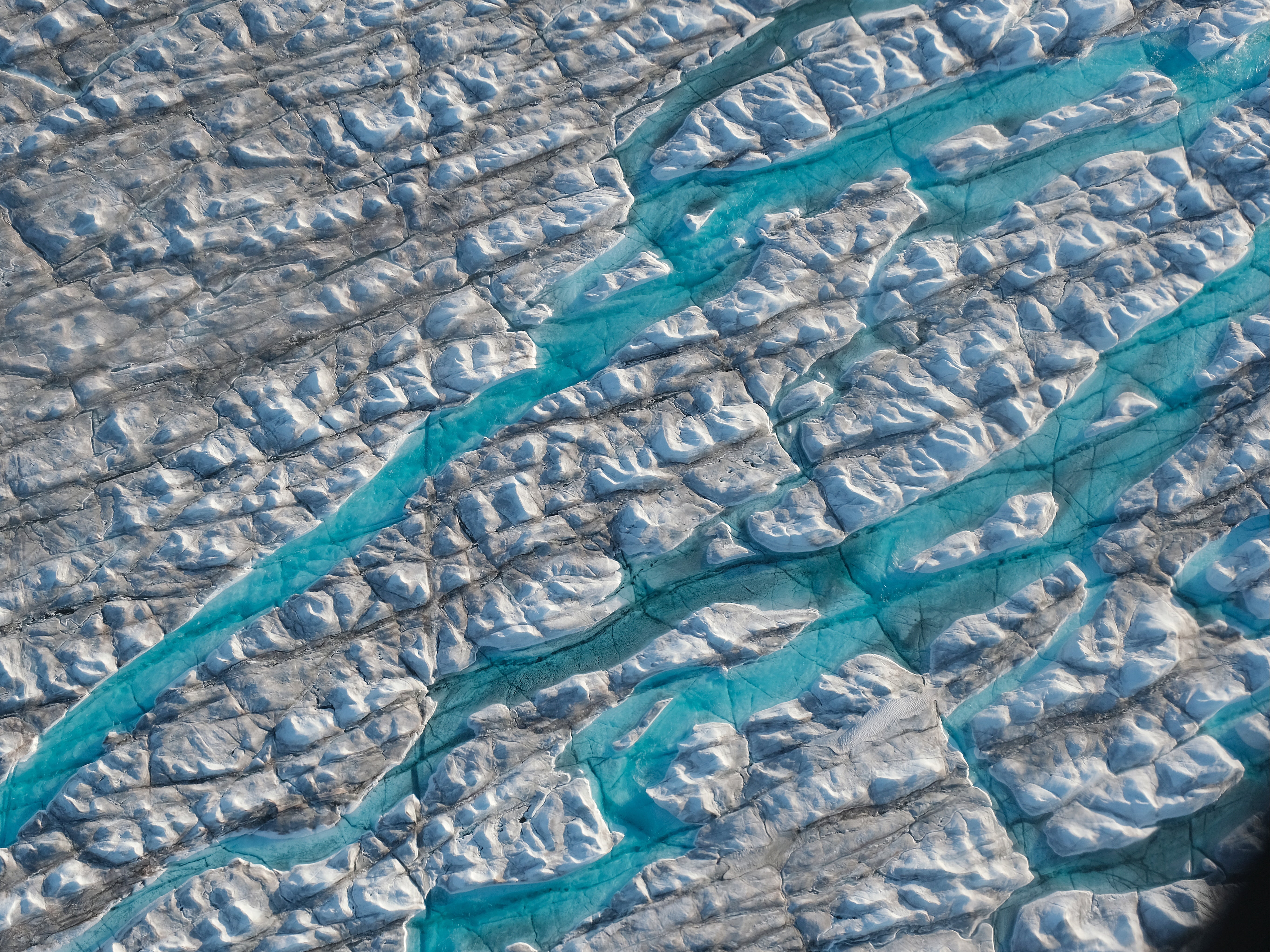

Greenland ice sheet melting may soon pass point of no return, study warns

‘We might be seeing the beginning of a large-scale destabilisation,’ scientist warns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Part of the Greenland ice sheet could soon cross the point of no-return after which the rate of melting outpaces the rate of snow fall, scientists have warned.

Scientists analysing arctic data said the situation could soon reach a “tipping point” and warned that they “urgently” need to understand how the effects of melting affect each other.

The Greenland ice sheet contains enough water to raise the global sea level by seven metres, a change which would displace millions of people.

Losing it is expected to add to global warming and disrupt major ocean currents, monsoon belts, rainforests, wind systems and rain patterns around the world.

However, the researchers said their data is not as comprehensive as they would like, meaning they cannot make solid conclusions.

Dr Niklas Boers, from Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, said: "We might be seeing the beginning of a large-scale destabilisation but at the moment we cannot tell, unfortunately.

"So far, the signals we see are only regional, but that might simply be due to the scarcity of accurate and long-term data for other parts of the ice sheet."

He explained how an ice sheet can only maintain its size if the loss of mass from melting and calving glaciers is replaced by snow falling onto its surface.

The warming of the Arctic disturbs this mass balance because the snow at the surface often melts away in the warmer summers.

Melting will mostly increase at the lower altitudes, but overall, the ice sheet will shrink from a mass imbalance.

As this happens, a positive feedback mechanism kicks in - meaning as the ice sheet surface lowers, its surface is exposed to higher average temperatures, leading to more melting and the process repeats until the entire ice sheet is gone.

Beyond a critical threshold, researchers say, this process can not be reversed because, with reduced height, a much colder climate would be needed for the ice sheet to regain its original size.

Dr Boers, and his colleague Dr Martin Rypdal from the Arctic University of Norway, have found the data shows that the critical threshold has at least regionally been reached due to the last 100 years of accelerated melting.

They add an increase in melting will possibly be compensated, at least partly, by more snowfall as precipitation patterns over the ice sheet will change due to the changing ice sheet height.

However, if the Greenland ice sheet as a whole moves into accelerated melting there will be severe consequences for the entire planet.

Dr Boers added: "We need to monitor also the other parts of the Greenland ice sheet more closely, and we urgently need to better understand how different positive and negative feedbacks might balance each other, to get a better idea of the future evolution of the ice sheet."

The research has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

Additional reporting by SWNS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments