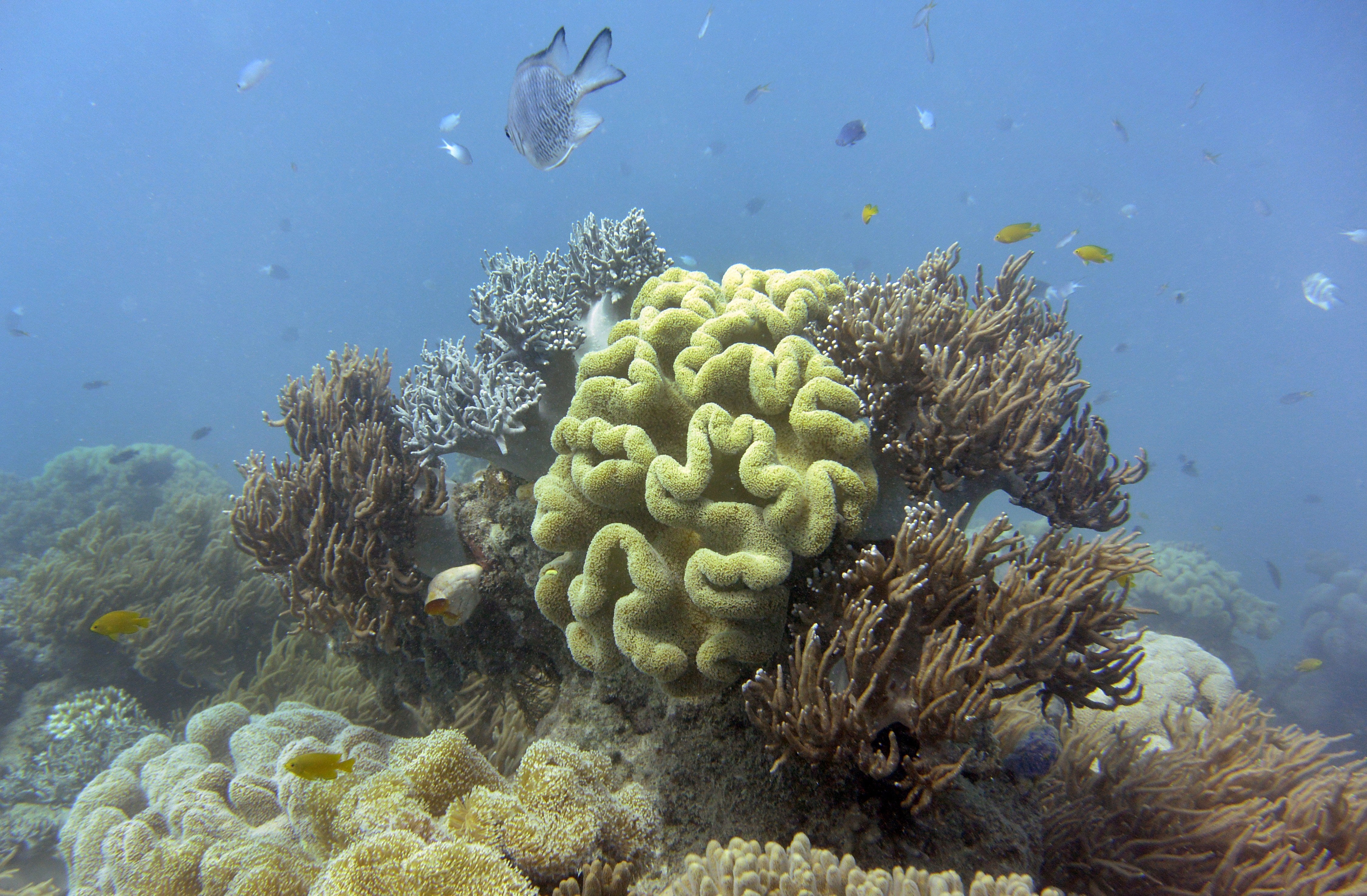

Fish on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef are losing their colour as corals die

‘Future reefs may not be the colourful ecosystems we recognise today’

Brightly coloured fish are becoming increasingly rare as corals are dying off in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and this phenomenon could become worse in the future, says a new study.

Over the past 30 years, global warming and ocean acidification have caused profound changes to the world’s largest natural reef system, leading to corals dying out on a large scale, said the study’s lead author, Christopher Hemingson of Australia’s James Cook University.

The diversity of fishes of different colours living in the ecosystem has declined sharply since the 1998 global coral bleaching event that led to a large section of the Great Barrier Reef dying off, found the study, published last week in the Global Change Biology journal.

Reefs, dubbed the ocean’s rainforests, cover less than 1 per cent of the global ocean floor but support nearly a quarter of all known marine species.

Bleaching events can leave these communities of interdependent marine species extremely vulnerable.

“We found that as the cover of structurally complex corals increases on a reef, so does the diversity and range of colours present on fishes living in and around them,” Dr Hemingson said in a statement.

“But, as the cover of turf algae and dead coral rubble increases, the diversity of colours declines to a more generalised, uniform appearance.”

In the study, scientists used a community-level measure of fish colouration and explored the links between fish community colouration and the environment.

They said corals and the structure of the seafloor play a significant role in shaping fish colouration.

“Having places to hide from predators may have allowed reef fishes to evolve unique colourations due to a reduced reliance on camouflage to avoid being eaten,” Dr Hemingson explained.

“Unfortunately, the types of corals [massive and boulder corals] most capable of surviving the immediate impacts of climate change are unlikely to provide these refuges. Fish communities on future reefs may very well be a duller version of their previous configurations, even if coral cover remains high,” he added.

With the Great Barrier Reef under increased threat and struggling to maintain its Unesco World Heritage Site status, scientists said “future reefs may not be the colourful ecosystems we recognise today, representing the loss of a culturally significant ecosystem service.”

Because of unusually warm ocean temperatures in 2016, 2017 and 2020, the reef suffered significant coral bleaching – with previous bleaching events damaging over two-thirds of the corals.

An earlier study published in 2020 also found that the number of small, medium and large corals on the Great Barrier Reef has declined by more than 50 per cent since the 1990s.

Researchers said the loss of colourful fishes may not have a huge impact if assessing reefs through a strictly functional or ecological lens, but add that the loss of this colour diversity “may trigger a broad range of human responses, including grief”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks