Fracking boom has ‘dramatically increased’ global methane emissions, study warns

If rise continues it will undercut efforts to meet international targets, research concludes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fracking has “dramatically increased” global methane emissions in the past decade, a new study has warned.

A rapid rise in levels of the greenhouse gas in recent years has been attributed to biological sources such as cows, tropical wetlands and rice fields, but the research reveals the contribution made by the controversial extraction process.

Researchers from Cornell University looked at the “chemical fingerprint” of methane in the atmosphere and concluded around a third of emissions in the past decade have come from fracking.

Methane levels rose steadily in the last decades of the 20th century before levelling off for the first decade of the 21st, but since 2008 they have been rising rapidly again.

If the rise continues in coming decades, it will significantly increase global warming and undercut efforts to meet international targets to curb dangerous climate change under the Paris Agreement, the study warns.

Each source of methane gives the gas a different chemical signature, relating to the weight of the carbon atom at the centre of its molecule.

Methane from fossil fuels has higher concentrations of the heavier carbon-13 variant compared with lighter carbon-12, while the gas emitted from biological sources is lighter, with less carbon-13.

The rise in methane since 2008 has also seen the carbon composition of the gas change, with lower levels of carbon-13. This led experts to attribute the spike to biological sources, most likely tropical wetlands, rice culture or animal agriculture.

But the research shows methane that leaks or is vented from the process of fracking for shale gas also has a lower carbon-13 content than conventional fossil fuels.

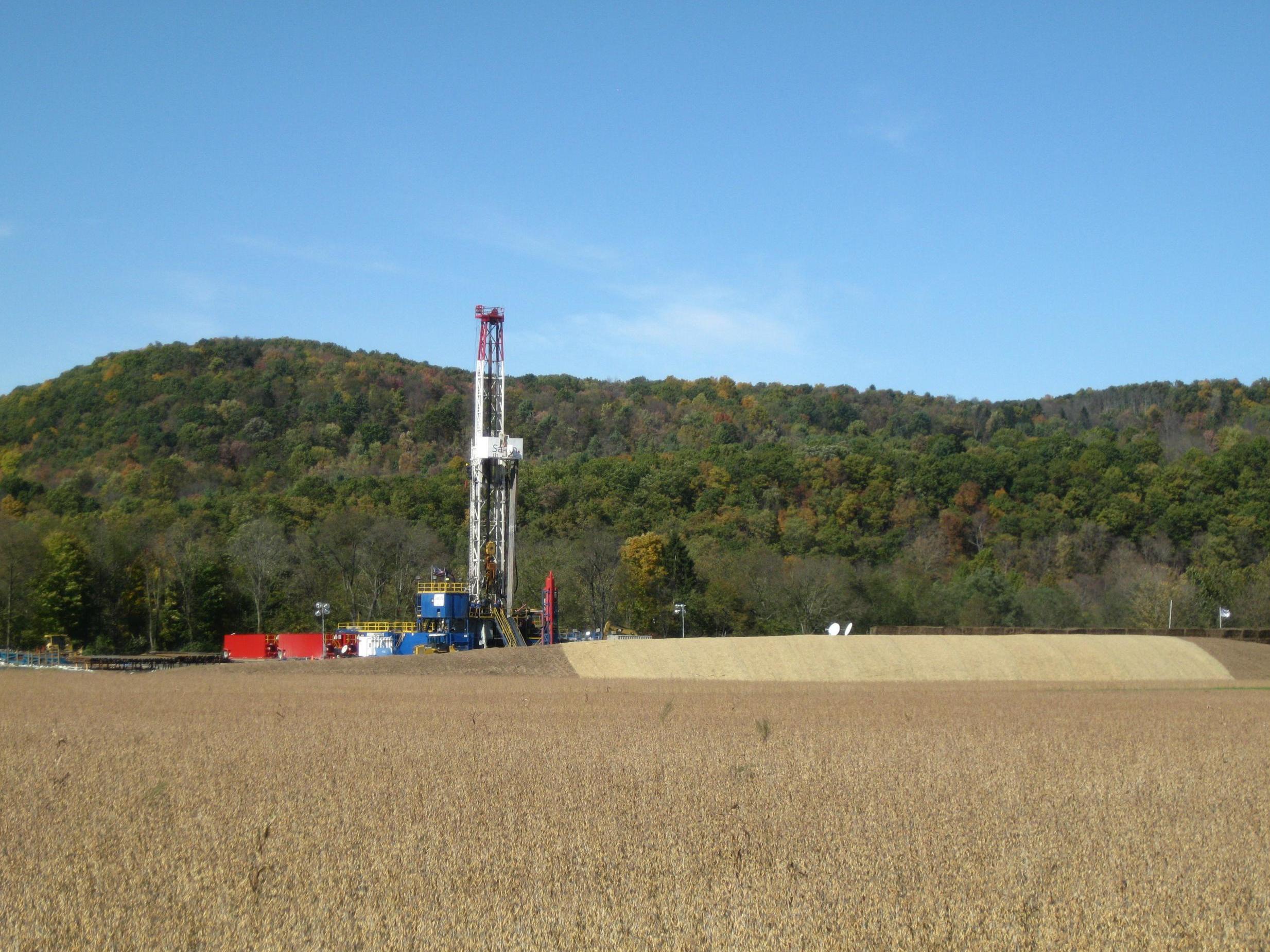

There has been a boom in the US exploiting shale gas through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which involves pumping liquid at high pressure deep underground to fracture shale rock and release gas.

The study concludes that methane from fossil fuels has probably exceeded emissions from biological sources in the past decade – with shale gas accounting for more than half of the total from fossil fuels.

Around a third of the total increased emissions from all sources globally over the past decade is down to shale gas production, according to the study published in Biogeosciences, a journal of the European Geosciences Union.

The study said: “The commercialisation of shale gas and oil in the 21st century has dramatically increased global methane emissions.”

Study author Professor Robert Howarth said the recent increase in methane “is massive”.

“It’s globally significant. It’s contributed to some of the increase in global warming we’ve seen and shale gas is a major player.”

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, but while carbon dioxide has a long-term impact in the atmosphere the climate responds more quickly to changes in methane.

Professor Howarth said: “If we can stop pouring methane into the atmosphere, it will dissipate. It goes away pretty quickly, compared to carbon dioxide. It’s the low-hanging fruit to slow global warming.”

In the UK, the Committee on Climate Change has warned that emissions from nascent shale gas industry must be strictly limited with tight regulation, close monitoring and rapid action to address methane leaks.

But the study said that given its finding that gas – both shale and conventional – was responsible for much of the recent increase in methane, “the best strategy is to move as quickly as possible away from natural gas”, warning it was not a “bridge fuel” from fossil fuels such as coal to cleaner technology.

Professor Grant Allen from the University of Manchester, who was not involved in the research, said: “Controlling emissions from fracking, and fossil fuels in general, represents a potential policy quick fix to stemming the rise of methane still further.

“If we can control the manmade methane emission sources that we can, then methane levels could yet be stabilised. However, natural climate feedbacks could override this intervention in a warmer future if we do not also simultaneously control carbon dioxide emissions now.

“A wholesale approach to reducing all controllable forms of greenhouse gas emissions is required to avoid this.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments