‘Does someone need to die?’ The families whose homes have turned into Britain’s earthquake zone – thanks to fracking

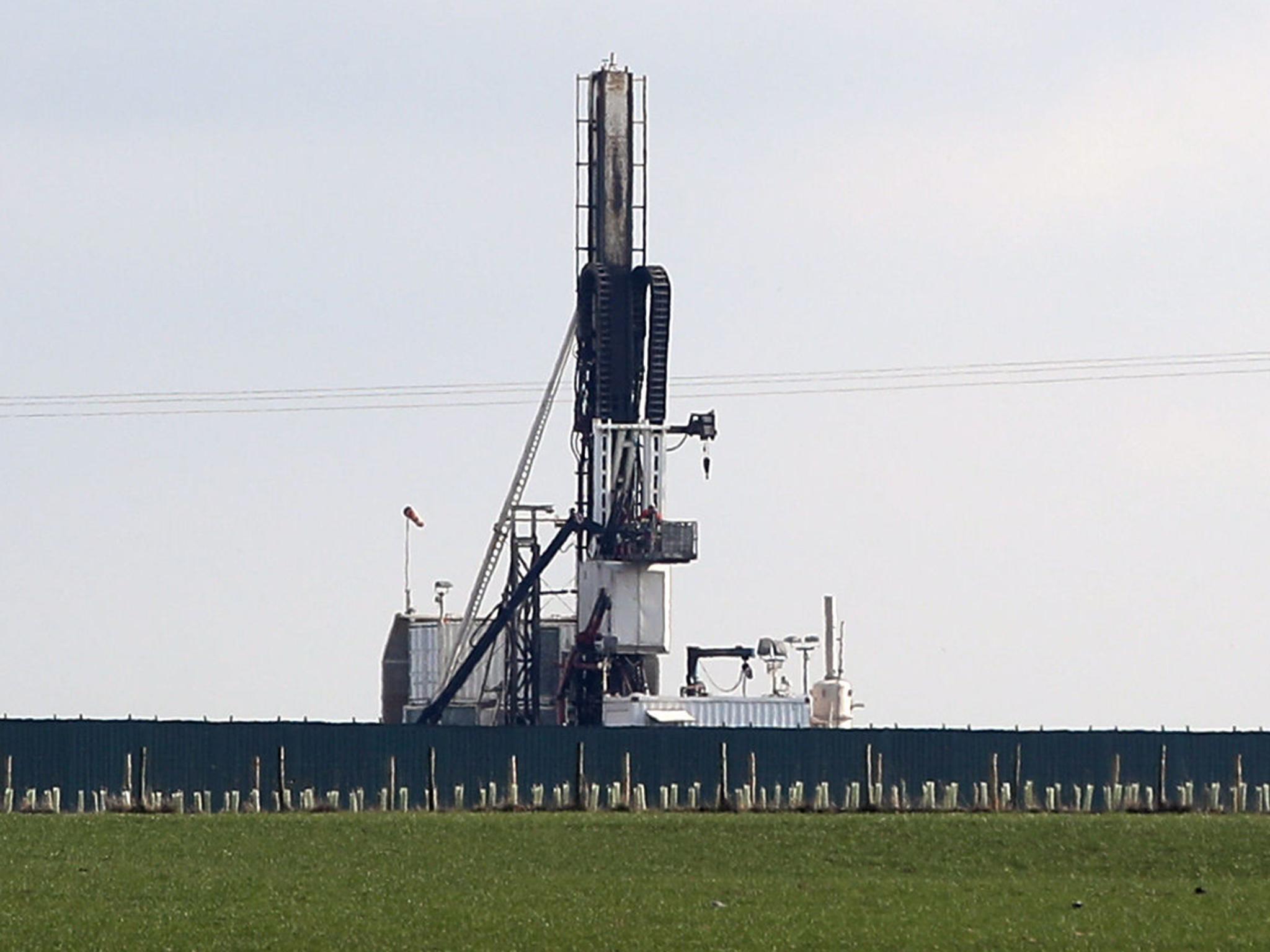

Drilling at the UK’s only shale gas site has led to repeated tremors – and locals fear bigger shakes are ahead if work restarts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Miranda Cox was enjoying a morning cup of tea in bed at her home in Kirkham, Lancashire, when the earthquake struck.

It lasted barely a few seconds and caused no real damage but it was, she says, one of the most terrifying experiences of her life.

“Part of me thinks, ‘Well, I didn’t even spill my brew so how bad was it?’” the 50-year-old tells The Independent. “But you don’t feel so calm when it’s happening. When your entire house is rumbling – it’s traumatising. My first instinct was, ‘What do we do if it starts collapsing? How do we get out?’ And then it stopped and, of course, everyone is okay. But it weighs on your mind. I keep thinking: what if the next one is bigger? What if it doesn’t stop so quickly?”

The mother-of-two lives in what, over the last two weeks, has become England’s most seismically active region.

There have been nine quakes in this part of Lancashire above 0.5 on the Richter scale since Wednesday. The biggest of these – that which jolted Ms Cox in bed – was a 2.9 shaker on bank holiday Monday, felt from Blackpool to Preston. Pictures posted online showed garden walls toppled and cracks in ceiling plaster. It was followed just 14 hours later by a 1.0 tremor.

But if residents fear what else may follow, they are also angry – because these quakes are no act of nature. They are almost certainly manmade. The earth shaking has coincided exactly with the recommencing of drilling nearby at the UK’s only active fracking site.

“They are making us live in an earthquake zone,” says Ms Cox, a long-term campaigner against fracking there. “Making people live with this constant danger is unforgivable.”

Work at the hugely controversial shale gas site – just off Preston New Road near Little Plumpton village – has now been indefinitely suspended while the Oil and Gas Authority investigates the seismic activity.

But residents are demanding more than a mere a moratorium.

On Tuesday, they delivered an open letter to Cuadrilla – the company that runs the site – demanding it is now mothballed for good. On Wednesday, as rain poured, more than 40 people picketed the site itself. Many dressed themselves in white as a sign of peaceful protest.

“You don’t come out in weather like this unless you are being pushed beyond your limits,” noted 63-year-old Barbara Richardson, a campaigner with Frack Free Lancashire, from under a sodden umbrella. “But what’s being done to us – and to the future generations who will have to live with the consequence – isn’t right. We have to fight it. We have no other option.”

Tensions run especially high here because fracking – the process of using high-pressure chemicals to extract gas from underground rocks – has never been wanted by many.

Campaigners have regularly protested at the site since it was first proposed in 2013. Among their numbers have been Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace activists but most of those who turn up, week in, week out, are simply residents concerned by both the earthquakes and environmental damage, including high-level emissions and toxic waste. Because many are women of a certain vintage, they have nicknamed themselves the Lancashire Nanas and – as a symbol of this – quite often don tabards.

“Because nanas get things done,” Tina Rothery, the group’s de facto spokeswoman previously told The Independent. “And, believe me, we will get this done. We will get fracking stopped.”

Indeed, these recent tremors may, in the long-run, help with this goal. A smaller quake measuring 2.3 on the Richter scale led to the UK’s only other fracking site being shut down permanently in Blackpool in 2011. “It’s now time for the same thing to happen here,” says Tina, a 57-year-old grandmother-of-one. “Isn’t it common sense that you don’t start earthquakes in places where people live?”

Drilling at the Preston New Road site itself started just last year. It did so only after initial proposals to frack the area were rejected by Lancashire County Council – but then approved on appeal by the government.

An initial exploratory drilling period between October and December 2018 led to more than 50 incidents of seismic activity being recorded by the British Geological Survey. After an eight-month pause since then, drilling started on a second well on 15 August. The first seismic activity came within hours.

“I wouldn’t say I was scared [when the house shook],” says Julia Stribling, a 70-year-old retired pharmaceutical dispenser who lives just off the Preston New Road. “I’m a Lancashire woman. Being scared isn’t in my nature. But it’s unsettling. My husband was looking at me wondering what was happening. I was looking at our family antiques in the cabinet. If they got smashed, I don’t know what I’d do. They don’t have much value but they’re priceless to me … It’s things like that that Cuadrilla don’t care about. They wouldn’t compensate me for smashing my mum’s heirlooms.”

The company itself did not respond to The Independent’s request for comment but, in an earlier statement, said it appreciated the tremor had “caused concern” for people.

“It is worth noting,” it said in a statement on the 2.9 shaker, “that this event lasted for around a second and the average ground motion recorded was 5mm per second. This is about a third of that permitted for construction projects.”

Longer-term, it says, fracking can meet huge swathes of the UK’s energy needs and is environmentally cleaner than traditional fossil fuels, if not renewable sources.

The Oil and Gas Authority, meanwhile, said that “operations at the site will remain suspended for as long as it takes for our scientists to examine the data from what happened over the weekend – there’s no fixed timeframe”.

Yet such assurances, here among the campaigners, seem unlikely to appease.

They say that fracking should not only be ended in Lancashire but outlawed across the country to prevent future sites ever being set up – a policy which would only put England in line with Germany, France, Scotland and Wales.

“A temporary shutdown isn’t good enough anymore,” says Ms Cox again. “One of these days one of these quakes is going to cause things to fall down and put lives in danger. Does someone really need to die before, as a country, we finally say we can’t allow this any longer?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments