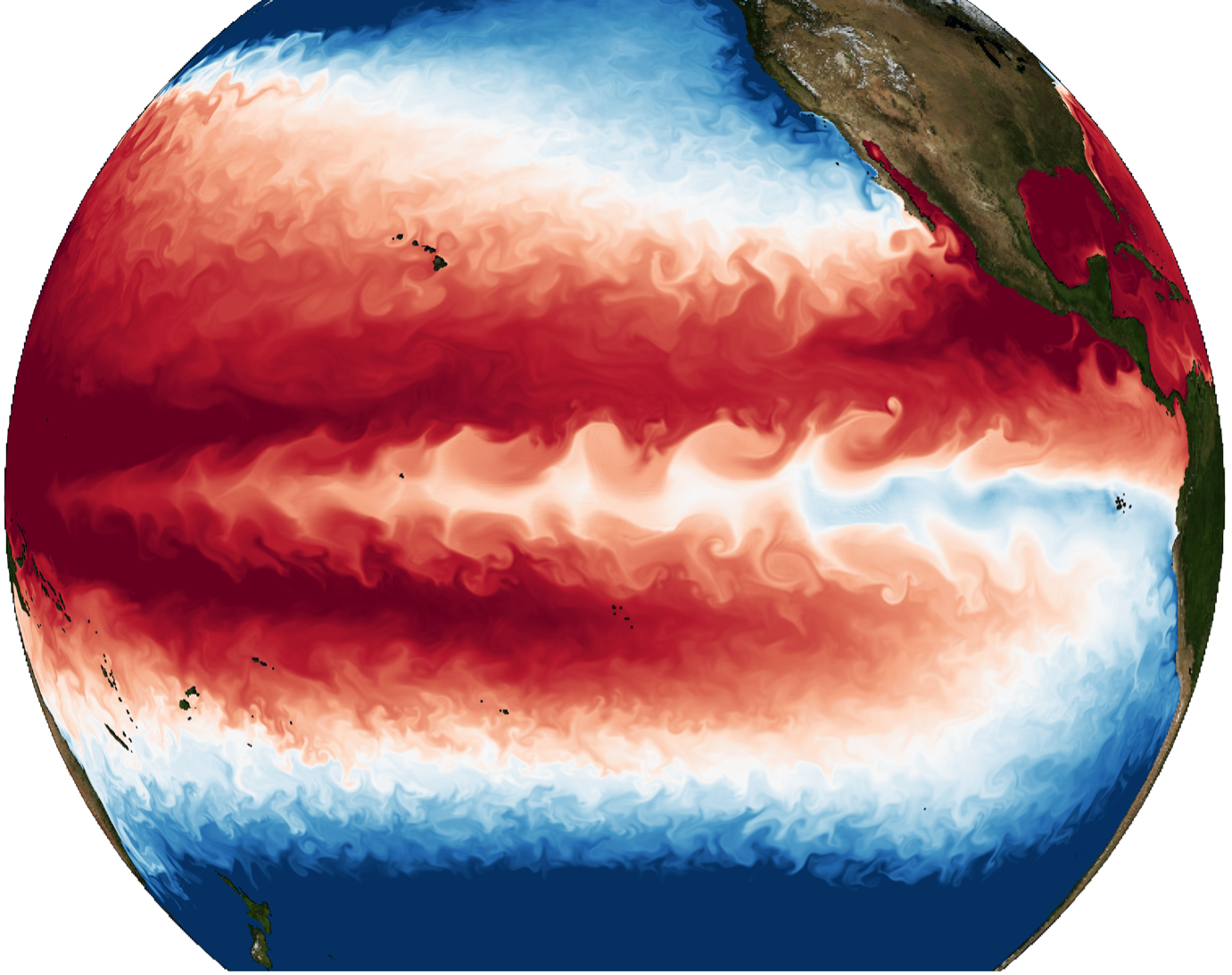

Climate crisis could lead to weaker El Niño and La Niña weather cycles

Human-led climate change is likely to affect the major weather phenomenon in unpredictable ways

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The cycling through warm El Niño and cold La Niña conditions in the eastern Pacific could be weakened by climate change – and scientists don’t know what the ecological effects will be.

The weather phenomenon, commonly referred to as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), has persisted without major interruptions for at least the last 11,000 years.

But this may change, according to a new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change by a team of scientists from the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) at Pusan National University in South Korea, the Max Planck Institute of Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany, and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, USA.

El Niño affects the global climate and disrupts normal weather patterns, which as a result can lead to intense storms in some places and droughts in others. Developing countries that depend on agriculture and fishing, particularly those bordering the Pacific Ocean, are usually most affected.

The team conducted a series of global climate model simulations using one of South Korea’s fastest supercomputers, Aleph, to realistically simulate tropical cyclones in the atmosphere and tropical instability waves in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, both of which play fundamental roles in the generation and termination of El Niño and La Niña events.

The team looked at how ENSO will change in response to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations.

“The result from our computer simulations is clear: Increasing CO2 concentrations will weaken the intensity of the ENSO temperature cycle,” says Dr. Christian Wengel, first author of the study and former postdoctoral researcher at the ICCP, now at the Max Planck Institute of Meteorology in Hamburg in Germany.

By tracing the movement of heat in the atmosphere and ocean system the scientists identified that future El Niño events will lose heat to the atmosphere more quickly due to the evaporation of water vapour, which has the tendency to cool the ocean.

“There is a tug-of-war between positive and negative feedbacks in the ENSO system, which tips over to the negative side in a warmer climate. This means future El Niño and La Niña events cannot develop their full amplitude anymore” said ICCP alumni Prof. Malte Stuecker, co-author of the study and now assistant professor at the Department of Oceanography and the International Pacific Research Center at the University of Hawaiʻi.

Even though the year-to-year fluctuations in eastern equatorial Pacific temperatures are likely to weaken with human-induced warming according to this new study, the corresponding changes in El Niño and La Niña-related rainfall extremes will continue to increase due to an intensified hydrological cycle in a warmer climate, as shown in recent studies by scientists from the ICCP and their international collaborators.

“Our research documents that unabated warming is likely to silence the world’s most powerful natural climate swing which has been operating for thousands of years. We don’t yet know the ecological consequences of this potential no-analogue situation“ says Axel Timmermann, “but we are eager to find out”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments