Earthrise: the image that changed our view of the planet

In the second part of our landmark series, Michael McCarthy travels back in time to Christmas Eve, 1968 – and the groundbreaking picture that transformed our attitude to a world we had hitherto taken for granted

It has been part-religion and part socio-political crusade, and has penetrated all corners of the globe. It has swept up young people – and not a few of their elders – into its embrace and on Saturday it is 50 years old. But how much of a difference has the modern environment movement really made? We know the noble causes. They trip off our tongues, from banning whaling, halting deforestation and saving endangered species to mending the hole in the ozone layer and bringing a halt to global warming – never mind acid rain, nuclear power and genetically modified organisms.

This week in The Independent we will be trying to assess the Green movement's successes and failures in dealing with them, since it began with the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, the 1962 book which awoke in millions the sense that the Earth as a whole was threatened by human actions and needed to be defended. But to do so, we first need a feel for the history of the movement as a whole over the half-century of its existence.

We can recount it in a number of ways: through the progress of its ideas (such as that of sustainable development); through the birth and growth of its pressure groups (such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, both founded in 1971); through the rise of its influence in Big Government (the US Environment Protection Agency was founded in 1970; Britain's Department of the Environment in 1972) or even through the record of its giant conferences, such as the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 which has a successor meeting – 20 years on – taking place in Rio next week.

But perhaps the most powerful way is to recount it through its people. They are overwhelmingly the idealistic activists of the environmental pressure groups around the world who down the years have not only protested at despoliation of the planet, they have taken direct action to try to stop it – and let this be said, have done so in the Greenpeace tradition of resolute non-violence. Most of them are of course anonymous, until sometimes they pay the ultimate price, like Fernando Perreira, the photographer killed when French agents blew up the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour in 1985, or Chico Mendes, the rainforest activist assassinated by Brazilian ranchers in 1988.

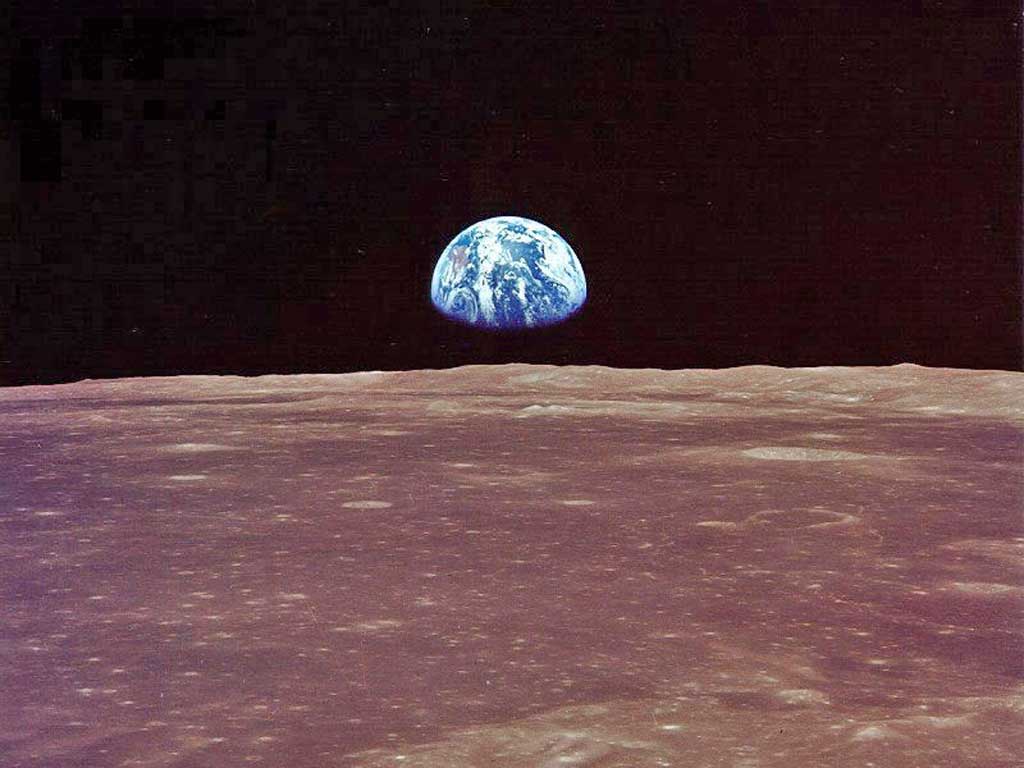

But some personalities do emerge with key ideas or actions, at key moments, and the first one is a name that will surprise most people: William Anders. Anders was an US astronaut, one of the crew of Apollo 8, the first manned spacecraft to leave the Earth's orbit and circle the Moon. When, on Christmas Eve 1968, he and his fellow crewmen Frank Borman and Jim Lovell emerged in their craft from behind the Moon's dark side, they saw in front of them an astounding sight – an exquisite blue sphere hanging in the blackness of space.

The photograph Anders took is known as "Earthrise", and its taking was without doubt one of the most profound events in the history of human culture, for at this moment we truly saw ourselves from a distance for the first time; and the Earth in its surrounding dark emptiness not only seemed infinitely beautiful, it seemed infinitely fragile. This wonderful image crystallised and cemented the sense of the planet's vulnerability which Silent Spring had awoken six years earlier. Its effect was enormous, not only because it stunned and amazed us, but because it fed into a burgeoning concept – that of Spaceship Earth.

This had been developed in a 1965 book of that name by one of the first "proto-environmentalists" to follow Rachel Carson, the British economist Barbara Ward-Jackson, and her idea of the planet as a craft with strictly limited resources – which the crew needed to look after with great care – struck a chord. When the Earthrise photograph appeared, there indeed it was – Spaceship Earth, with all its glory apparent, and all its limits.

A series of thinkers then began to explore these limits, and in two books in particular produced what we might term the first environmental scare stories. One was The Population Bomb by a biology professor at Stanford University, Paul Ehrlich, and the other was The Limits to Growth by a group of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology working under the label of The Club of Rome. Both confronted issues which still confront us today – the soaring rise in human numbers, and the finite nature of natural resources – but both made claims which now appear exaggerated, Ehrlich prophesying mass global starvation in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Club of Rome researchers suggesting many natural resources would have run out by 2000. However, at the time, they gave to nascent environmentalism its essential characteristic, its sense of urgency.

More lasting in its effect was a more unconventional critique: Small is Beautiful by the British economist E F Schumacher, published in 1973. Subtitled "A study of economics as if people mattered", the book was an attack on the dehumanising effect of massive companies and the continuing belief of most economists that bigger was better For this, it is as loved by environmentalists today as it was on its appearance four decades ago.

But the profoundest of all the books to have appeared during the Green movement's 50 years is undoubtedly Gaia, the revolutionary look at life on Earth by the British scientist James Lovelock, which appeared in 1979. Lovelock's idea was that the planet behaved like a single giant organism – that it possessed a planetary-scale control system which itself kept the environment fit for life. It was an entirely scientific study, but his naming the system after the Greek goddess of the Earth gave it a mystic flavour which appealed to many environmentalists, and if Earthrise is the Green movement's iconic image, Gaia might be said to be its sacred text.

There have been other texts which are vital, of course, such as Our Common Future, the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland, the former premier of Norway, which popularised the idea of sustainable development – the idea that poor countries could grow out of poverty without trashing their natural resource base. Even a book like The Green Consumer Guide of 1988, by John Elkington and Julia Hailes, was important in showing how consumers' purchasing decisions could have a huge environmental effect.

It is surprising, perhaps, that there is not a single book which stands out about the most serious of all our environmental problems, which emerged half-way through the Green movement's 50 years: climate change.

But there is a key figure: James Hansen, the Nasa scientist who first alerted Americans to the dangers of global warming more than 25 years ago, and continues to do so today. Professor Hansen's single-minded insistence that the climatic future is truly perilous, however distracted we are by recessions or anything else, once again reinforces the fact that the people of the environment movement have been as vital as its ideas.

Green groundbreakers: Seven books that define the movement

Silent Spring: The book which started it all in 1962, showing how the Earth could be threatened by human actions.

The Population Bomb: Doomwatch-style 1968 predictions of mass starvation, which did not come true.

The Limits To Growth: More apocalyptic predictions, in 1972, of natural resources soon running out – also unrealised.

Small is Beautiful: EF Schumacher's much-loved account, published in 1973, of "a study of economics as if people mattered".

Gaia: The first completely new take on life on Earth since Darwin, put forward as a hypothesis by Jim Lovelock in 1979.

Our Common Future: The 1987 study which made familiar the idea of sustainable development. The Green Consumer Guide: The idea of environmental shopping took off when this guide came out in 1988.

Catch up on the series so far, follow the debate and have your say at www.independent.co.uk/green50

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks