Drug-resistant bacteria: Sewage-treatment plants described as giant 'mixing vessels' after scientists discover mutated microbes in British river

Exclusive: Discovery reveals role of sewerage plants in creating mutated microbes that are resistant to antibiotics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

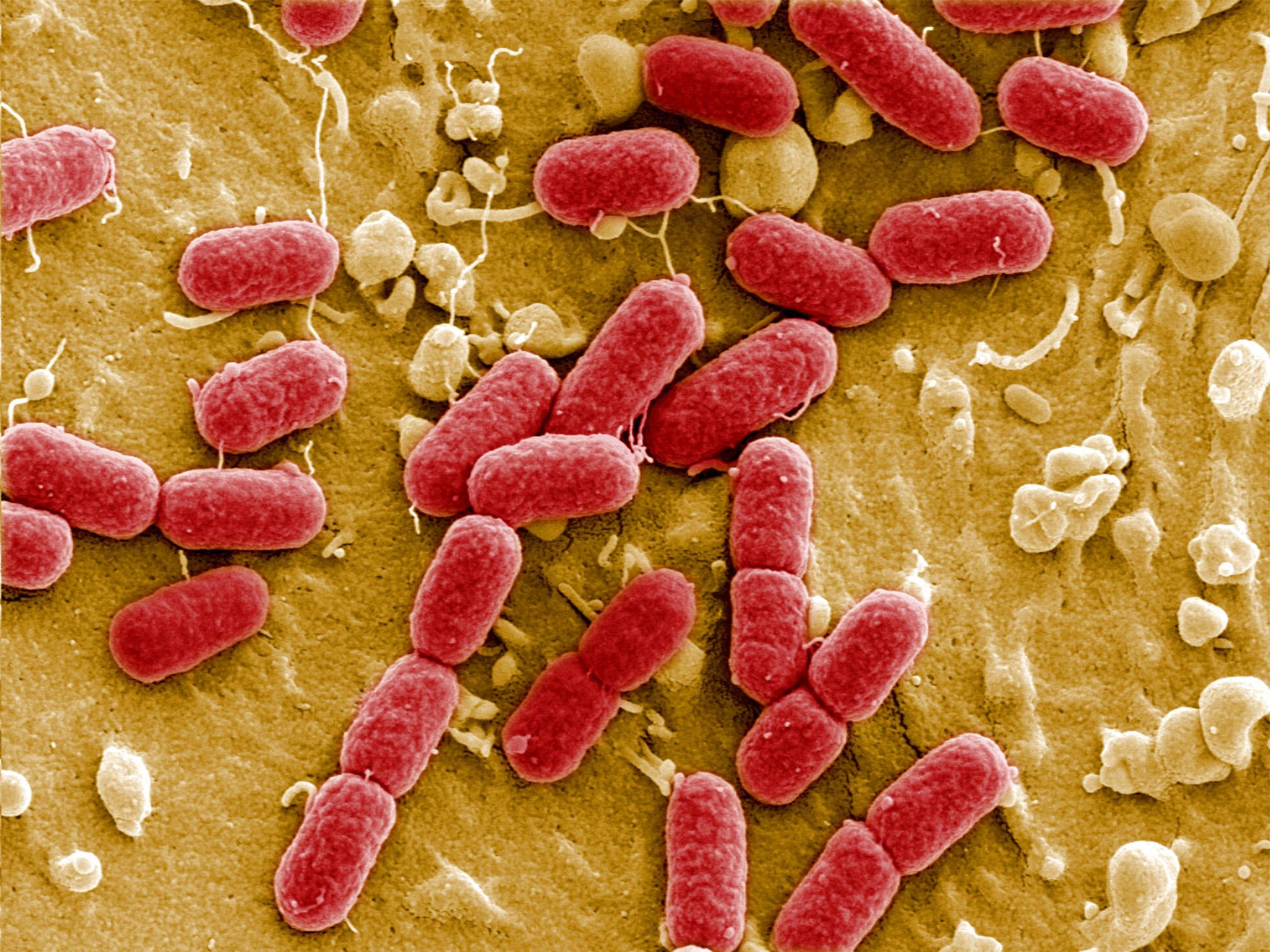

Your support makes all the difference.Superbugs resistant to some of the most powerful antibiotics in the medical arsenal have been found for the first time in a British river – with scientists pinpointing a local sewage-treatment plant as the most likely source.

Scientists discovered the drug-resistant bacteria in sediment samples taken downstream of the sewerage plant on the River Sowe near Coventry. The microbes contained mutated genes that confer resistance to the latest generation of antibiotics.

The researchers believe the discovery shows how antibiotic resistance has become widespread in the environment, with sewage-treatment plants now acting as giant “mixing vessels” where antibiotic resistance can spread between different microbes.

A study found that a wide range of microbes living in the river had acquired a genetic mutation that is known to provide resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, a class of antibiotics used widely to treat meningitis, blood infections and other hospital-acquired infections.

Within the river sediment, the scientists also found human gut bacteria that had developed resistance to another kind of antibiotic, called imipenem, which is administered by intravenous injections for severe infections not normally treatable with other antibiotics.

“These are frontline antibiotics and we were not expecting to see these kinds of levels of resistance to them in the environment. It is quite staggering,” said Professor Elizabeth Wellington of the University of Warwick, who led the study. “This is a worrying development and we need to be concerned about it. We’ve completely underestimated the role waste-treatment processes can play in antibiotic resistance,” she told The Independent.

Tests have shown that the level of antibiotic resistance is many times higher downstream of the Coventry sewage-treatment facility than it is upstream. “The way sewerage plants mix up different types of waste means they’re hotspots, helping bacteria share genes that mean they can deactivate or disarm antibiotics that would normally kill them,” Professor Wellington said.

“This is a big deal, because this is the most common bacterial resistance gene causing failures in treatment of infections, and it’s the first time anyone has seen this gene in UK rivers,” she added.

“The problem is we use river water to irrigate crops, people swim or canoe in rivers, and both wildlife and food animals come into contact with river water. These bacteria also spread during flooding, and with more flooding and heavy rain this could get worse.”

Stricter regulations and higher levels of sewage treatment, with an emphasis on preventing untreated sewage being discharged during a storm, are needed to halt the rise of antibiotic resistance in the environment, Professor Wellington said.

“We’re on the brink of Armageddon and this is contributing to it. Antibiotics could just stop working,” she added.

Earlier this month, David Cameron warned that the world could be “cast back into the dark ages of medicine” where people die of relatively trivial and treatable infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments