Did the first farmers deliberately domesticate wild plants?

New study finds little evidence that farmers consciously tried to turn wild plants into more useful crops

The beginning of agriculture changed human history and has fascinated scholars for centuries. Yet it’s hard to study because it happened 10,000 or so years ago. As a result, a number of important issues remain unresolved, including why hunter-gatherers first began farming, and how crops were domesticated to depend on people.

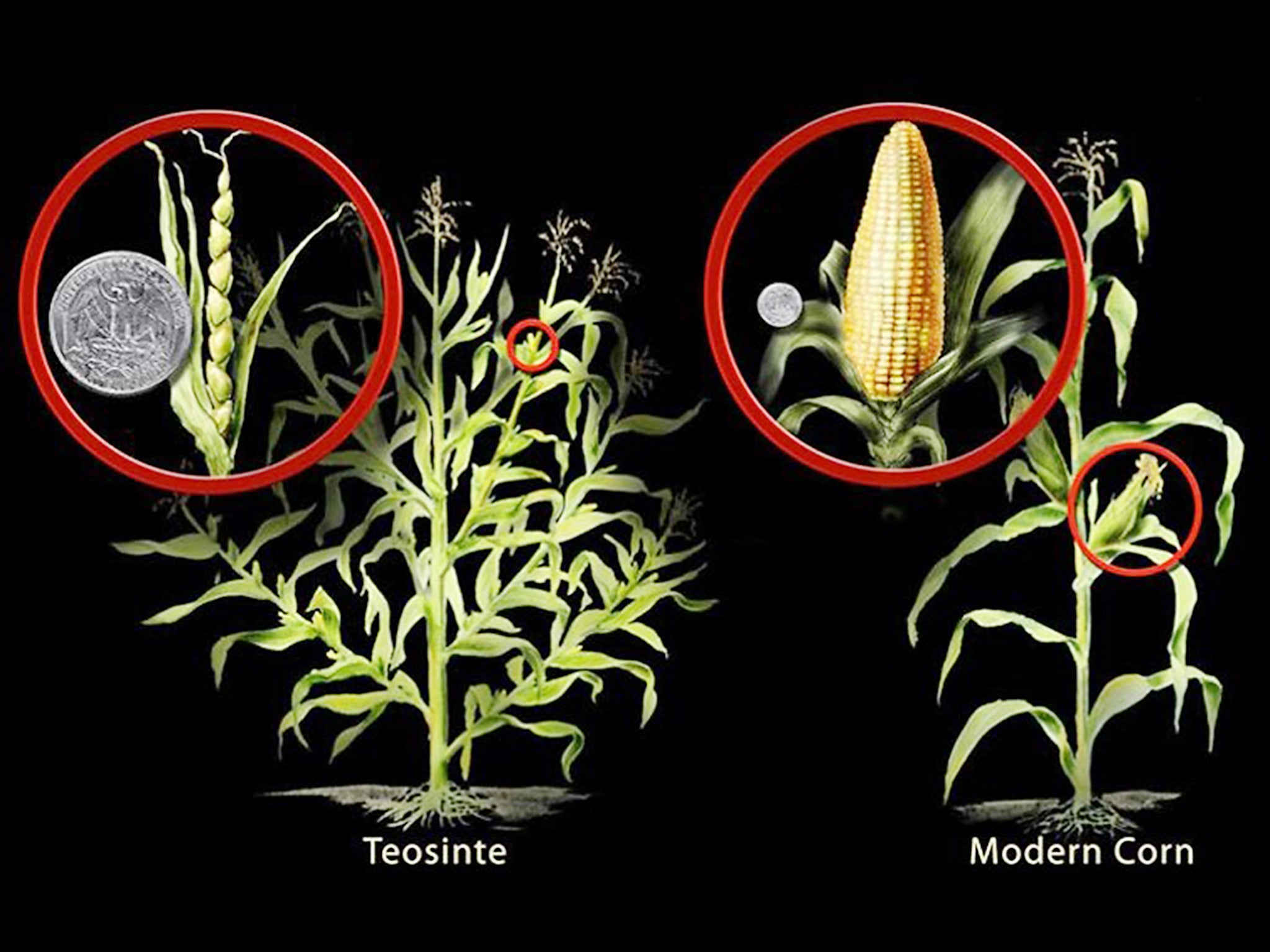

Domesticated crops have been transformed almost beyond recognition in comparison with their wild relatives. Look at how maize differs from its wild equivalents, for instance:

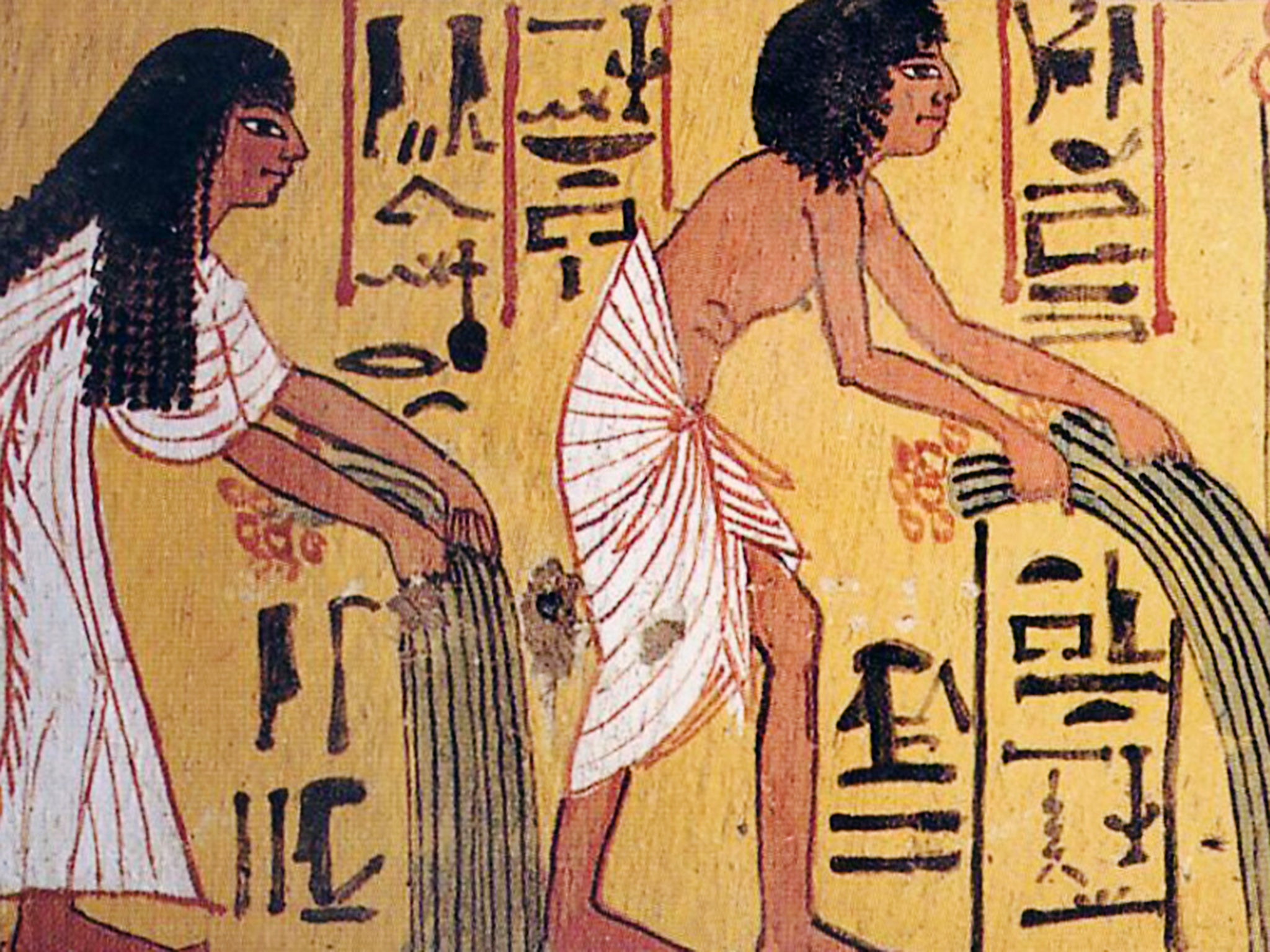

This transformation largely happened during the early stages of farming, back in the Stone Age, when crops were first deliberately sown, tended and harvested using stone sickles.

One controversy in this area is about the extent to which ancient peoples knew they were domesticating crops. Did anyone in 8,000BC think thin, wispy “teosintes” could one day become corn on the cob? Did anyone really look at wild rice and imagine turning it into basmati or long-grain? Many archaeologists think not, but it’s difficult to rule out deliberate breeding.

The question is whether these first farmers knowingly bred domesticated crops, or whether domestication characteristics simply evolved as farmers repeatedly cultivated and harvested wild plants?

To investigate this, colleagues and I have a new paper published Evolution Letters in which we looked at seed sizes in wild and domesticated plants. Domesticated cereal crops such as wheat, rice or maize have lost the ability to disperse their seeds naturally – they no longer fall off the plants by themselves, and instead depend on people or machines to plant them. Their seeds have become much larger, however. Maize seeds are 15 times bigger than wild teosinte, while soybeans are seven times larger than their wild relatives. Even in plants like barley, a more modest increase in seed size (60 per cent larger) translates into hugely increased yield.

Of course, the farmers who bred the early versions of these crops may have been targeting large seeds because they knew these would give larger yields. This is why we also compared cereal crops with vegetables. This gets around the problem of looking at seed size in crops that were grown for their grain.

Any selective breeding of vegetables by early farmers would have acted on the leaves, stems or roots that were eaten as food, but should not have directly affected seed size. Instead, any changes in vegetable seed size probably arose unintentionally.

Natural selection could have caused larger seeds to evolve in cultivated fields if larger seedlings competed or survived better than smaller ones. Larger seeds could also have resulted from genetic links to other characteristics like overall plant size. In this case, people might have bred larger crops by saving and planting seeds from the biggest plants, or unintentionally by thinning out small plants while preserving larger ones. But larger seeds would not have been inevitable – there are many plants which are large when mature, but grow from small seeds.

We gathered together seed size data for lots of modern crops and living examples of their wild relatives. Across seven vegetable species we found strong evidence for a general enlargement of seeds due to domestication. This is especially stunning in crops like potato, cassava and sweet potato, where people don’t even plant seeds, let alone harvest them. It is hard to think of any reason why people would breed large seeds in these crops. Instead, larger seeds in these species (found in the flowering plant above ground) surely arose unintentionally.

If early farmers unintentionally produced vegetables with larger seeds simply by cultivating them, then what about grain crops? The size of the domestication effect for vegetable seeds falls completely within the range seen in cereals and pulse grains like lentils and beans. This makes it likely that at least part of the seed enlargement in these crops also evolved during domestication without deliberate foresight from Stone Age farmers – people did not set out to breed larger grains, but these evolved through natural selection or genetic links to plant size.

Our findings have important implications for understanding how crops evolved. Unintentional selection was probably more important in the genesis of our food plants than previously realised. Early increases in the yields of crops might well have evolved in farmers’ fields rather than being bred artificially.

Colin Osborne is a professor of plant biology at the University of Sheffield. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks