How Japan’s 2011 tsunami sent species across the Pacific Ocean – on objects

The human cost of the natural disaster is well documented but new research reveals how it propelled invasive species en masse across the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a foreign species arrives in a new environment and spreads to cause some form of economic, health, or ecological harm, it’s called a biological invasion. Often stowing away among the cargo of ships and aircraft, such invaders cause billions of dollars of economic loss annually across the globe and have devastating impacts on the environment.

While the number of introductions which eventually lead to such invasions is rising across the globe, most accidental-introduction events involve small numbers of individuals and species showing up in a new area.

But new research published today in the journal Science has found that hundreds of marine species travelled from Japan to North America in the wake of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami (which struck the east coast of Japan with devastating consequences).

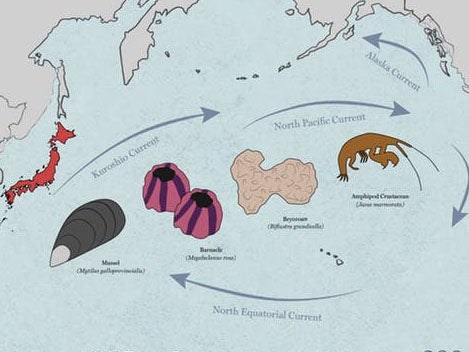

Marine introductions result from “biofouling”, the process by which organisms start growing on virtually any submerged surface. Within days a slimy bacterial film develops. Then in a period of months or even a few years (depending on the water temperature) fully formed communities may be found, including algae, molluscs such as mussels, bryozoans, crustaceans, and other animals.

Current biosecurity measures, such as antifouling on ships and border surveillance, are designed to deal with a steady stream of potential invaders. But they are ill-equipped to deal with an introduction event of the scale recorded along most of the North American coast. This would be just as true for Australia, with its extensive coastlines, as it is for North America.

This research, led by James Carlton of Williams College, for a few years after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, many marine organisms arrived along the west coast of North America on debris derived from human activity. The debris ranged from small pieces of plastic to buoys, to floating docks and damaged marine vessels. All of these items harboured organisms. Across the full range of debris surveyed, scores of individuals from roughly 300 species of marine creatures arrived alive. Most of them were new to North America.

The tsunami swept coastal infrastructure and many human artefacts out to sea. Items that had already been in the water before the tsunami carried their marine communities along with them. The North Pacific Current then transported these living communities across the Pacific to Alaska, British Columbia, Oregon, Washington and California.

Japanese tsunami buoy with Japanese oyster Crassostrea gigas, found floating offshore of Alsea Bay, Oregon in 2012. James T. Carlton

What makes this process unusual is the way a natural extreme event – the earthquake and associated tsunami – gave rise to an extraordinarily large introduction event because of its impact on coastal infrastructure. The researchers argue that this event is of unprecedented magnitude, constituting what they call “tsunami-driven megarafting”: rafting being the process by which organisms may travel across oceans on debris – natural or otherwise.

It’s not known how many of these new species will establish themselves and spread in their new environment. But, given what we know about the invasion process, it’s certain at least some will. Often, establishment and initial population growth is hidden, especially in marine species. Only once it is either costly or impossible to do something about a new species, is it detected.

Biosecurity surveillance systems are designed to overcome this problem, but surveillance of an entire coast for multiple species is a significant challenge.

Perhaps one of the largest questions the study raises is whether this was a one-off event. Might similar future occurrences be expected? Given the rapid rate of coastal infrastructure development, the answer is clear: this adds a new dimension to coastal biosecurity that will have to be considered.

Investment in coastal planning and early warning systems will help, as will reductions in plastic pollution. But such investment may be of little value if action is not taken to adhere to, and then exceed, nationally determined contributions to the Paris Agreement. Without doing so, a climate change-driven sea level rise of more than 1 m by the end of the century may be expected. This will add significantly to the risks posed by the interactions between natural extreme events and the continued development of coastal infrastructure. In other words, this research has uncovered what might be an increasingly common new ecological process in the Anthropocene – the era of human-driven global change.

Steven Chown is a professor of biological sciences at Monash University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments