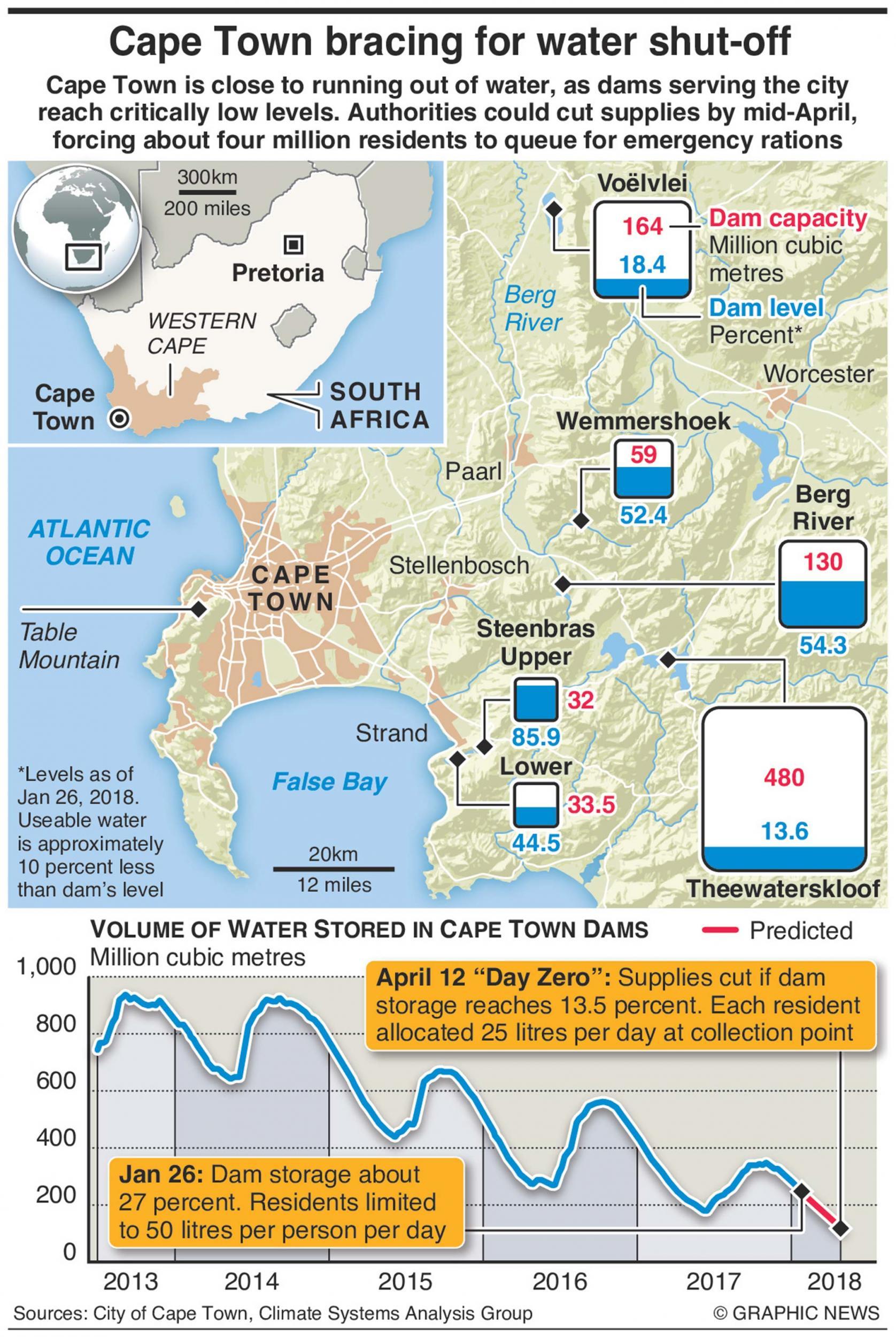

Day Zero: The city of Cape Town is about to run out of water – its main reservoir is only 12% full

More than a decade ago, South Africa was promised there would be no more hose-pipe bans. But the precautions put in place didn't work and now Cape Town is in critical danger of becoming the first city in the world to run out of water in May, says Dave Chambers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was around this time of year in 2005 when I took a 75-mile drive to Cape Town’s biggest reservoir with Saleem Mowzer, the African National Congress (ANC) councillor then in charge of water for South Africa’s second-largest city.

Theewaterskloof Dam was around 30 per cent full and it was a crisis. The following day, the newspaper where I was deputy editor published a photograph of Mowzer standing on the dam’s sandy bottom, dead trees from a long-ago-flooded valley sticking up like sentinels of doom in the background, under the headline: “Never again”.

Our report described the measures Mowzer and others were planning to ensure Cape Town would never again have to contemplate such horrors as hosepipe bans, which were about as bad as water restrictions got at that time.

Those plans included drilling seven boreholes into a massive underground trove of liquid treasure, the Table Mountain Group aquifer, estimated to contain 100,000 cubic kilometres of water.

Thirteen years later, Mowzer’s “never again” has arrived. Unfortunately, the boreholes haven’t, which is why Cape Town – with a population the size of Birmingham, Leeds, Glasgow, Sheffield, Bradford and Liverpool combined – is in critical danger of becoming the first city in the world to run out of water.

Today Theewaterskloof Dam – alone responsible for more than half of Cape Town’s surface water supply – is around 12 per cent full. For months we have been told the last 10 per cent is difficult to extract, but new pumping equipment which is being installed from this week will reduce the 10 per cent to 6 per cent.

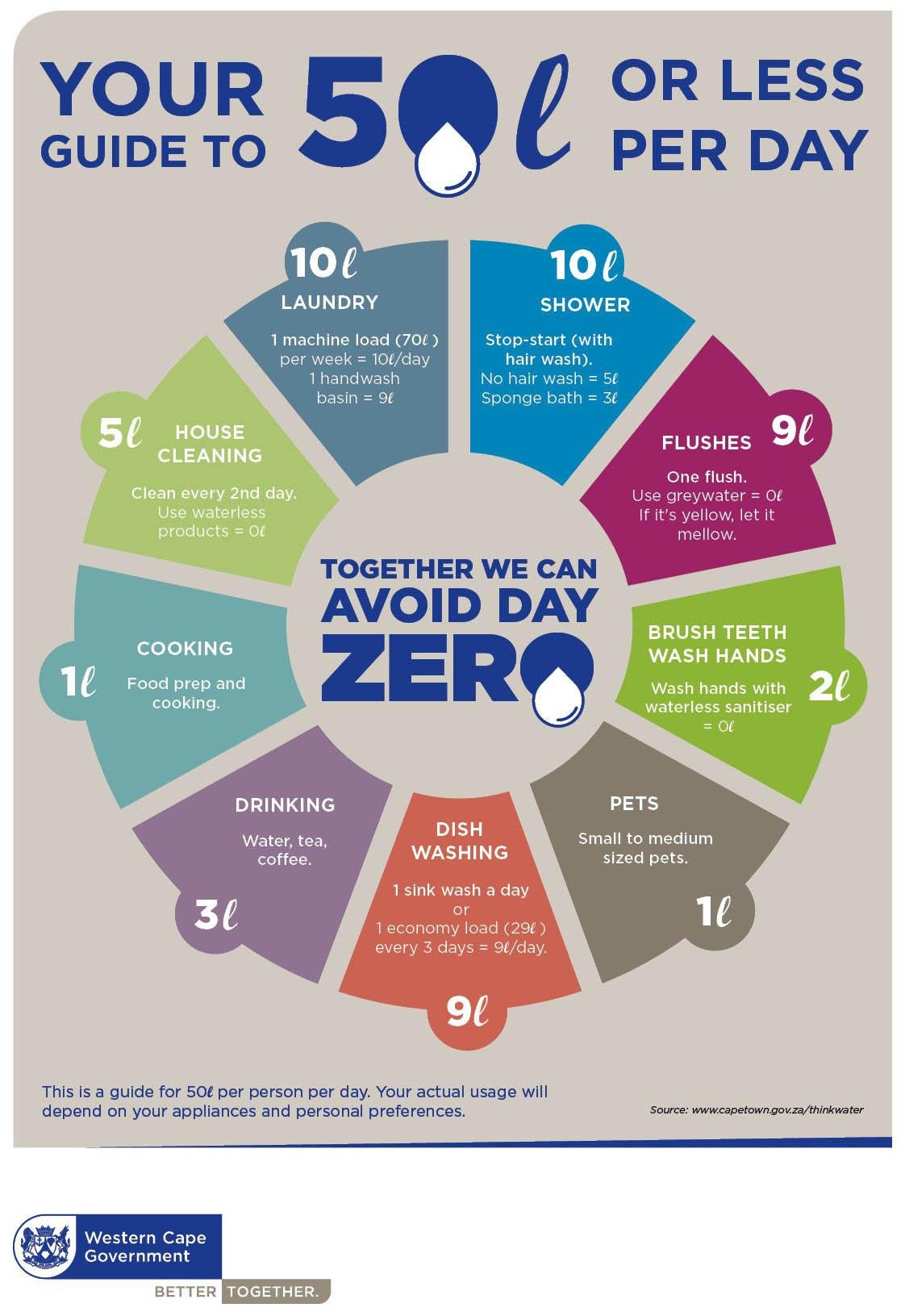

To put that effort into context, if Capetonians can stick to the 50 litres (11 gallons) a day they are now allowed, the puddle at the bottom of Theewaterskloof can keep the city going for 64 days. With the water in the city’s other five large reservoirs, there is still time for emergency augmentation projects to come on stream and for the winter rains to rescue us.

Mowzer and the ANC are long gone; an opposition coalition took control of Cape Town in 2006 and South Africa’s main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), now holds a two-thirds majority. But the problems they were grappling with when the population was 3.2 million are the same, just bigger.

Capetonians now number 3.8 million, 20 per cent more than in 2005. The increase is largely explained by internal migration from other provinces, chiefly people from the poverty-stricken Eastern Cape chasing the ANC’s much-vaunted dream of “a better life for all”.

Boreholes

There are 30,000 private boreholes in suburban gardens across Cape Town. But most of the water isn't drinkable. The super-rich are putting in reverse osmosis filtration systems so they can go off-grid. Most people who have existing boreholes are using the water for things like flushing the toilet and running the washing machine.

To an extent the DA, which also controls the Western Cape provincial government in South Africa’s three-tier system of government, has become a victim of its own success. For years, the province’s economic growth has outpaced the country’s, and the DA’s reputation for clean governance – in stark contrast to the scandals and corruption that have engulfed President Jacob Zuma’s national administration – has been a magnet for individuals and businesses alike.

Cape Town’s water resources have also grown. We might not have the boreholes envisaged in 2005, but eight years ago a new dam in the mountains 34 miles from Theewaterskloof boosted supply to the city by 17 per cent. So what’s the problem?

In a word: rain, or rather the lack of it. The weather station at Cape Town International Airport has recorded an annual average of 508mm since 1977 but the last three years have produced 153mm, 221mm and 327mm. Put another way, together they have yielded less rain than we had in the unusually soggy 1993.

This is the first time the winter rains have failed so spectacularly for three successive years. The 2005 crisis was precipitated by three years of poor winter rainfall, but collectively they were only 25 per cent below average. For the past three winters, they have fallen short by 55 per cent.

For that we have to thank the El Nino Southern Oscillation. Its effects on our weather have been so profound that the Climate System Analysis Group (CSAG) at the University of Cape Town is refusing to publish its rainfall forecast for a wet season that should start in May or June, saying short-term predictions have become unreliable.

Fact box

Most houses are collecting grey water – water that’s been used in sinks, dishwashers, showers and baths – which can be reused for some purposes without purification; for example shower water can be used to flush the loo, and bath water can be used to water the garden. People tend to store it in water butts in a far corner of the garden, where it smells really bad…

Perhaps with an eye to a war of words over dodgy rainfall predictions that broke out two weeks ago between Western Cape Premier Helen Zille and the South African Weather Service, CSAG scientist Chris Jack told The Sunday Times in South Africa at the weekend: “We should be aware of the implicit power behind ‘scientists say’ and be willing to undermine that by saying ‘we don’t know’ when we don’t know. We also need to be far more critical of our own work and its limitations.”

To be fair to the climatologists and meteorologists, they can hardly be blamed for three dry winters. Even if they’d predicted them, we probably wouldn’t have believed them; after all, it’s never happened before, and water scientists are now saying this is a one-in-400 year event.

In other words, Cape Town has probably not seen anything like this since Jan van Riebeeck came ashore in April 1652 and took advantage of the bountiful streams and springs flowing off Table Mountain to plant the gardens, fields and vineyards which provisioned the Dutch East India Company’s passing ships.

Fast-forward 366 years and the big question – in fact, the only question – on Capetonians’ minds is whether we can avoid “day zero”, the term coined by the City of Cape Town for when the taps will be turned off. The plan is to pull the plug when reservoirs collectively sink to 13.5 per cent. This will preserve a “lifeline” supply, to be doled out at the rate of 25 litres a day per person at emergency collection points guarded by soldiers.

Minister of Water and Sanitation Nomvula Mokonyane is irritated with the city council for inventing day zero. She says it is causing unnecessary panic and her department, which is responsible for supplying water in bulk to local councils, is “not planning for the system to fail”.

The opposition-run city and provincial governments are irritated in return, saying they are receiving precious little support for the emergency desalination, groundwater-extraction and recycling projects they have launched to boost the city’s water supply. There is already talk of legal action once the dust has settled (hopefully under torrential winter downpours) to recover the cost of these projects from Mokonyane’s department. Cape Town says it has a R1.7 bn (£100m) hole in its budget.

Bickering aside, can day zero be avoided? There are reasons for optimism, and one of them is good old market forces. After months of dithering, begging and insulting (three weeks ago mayor Patricia de Lille said citizens who refused to reduce water consumption were “callous”), the price of water was sharply increased on 1 February.

In a conversation in her office in December, De Lille told me this was something she would never do. In January, however, the DA decided she was not up to the job of handling the crisis and made her deputy responsible. The new tariffs she didn’t want mean people who keep their monthly household consumption to 6,000 litres (1,320 gallons) will pay only R100 (£6) more. But those who get through 50,000 litres (11,000 gallons) will see their monthly bill jump by 613 per cent from R2,889 (£170) to R20,619 (£1,213).

The second reason for optimism, as long as you’re not a farmer, is that agriculture’s water supply is being reduced in line with an agreement with the National Department of Water and Sanitation. The sector is currently drawing about 30 per cent of the water in the supply scheme, which will fall to 15 per cent in March and 10 per cent in April.

Third, it’s early days but Cape Town is becoming less reliant on its reservoirs. In the week ending January 29, 24 million litres (5.3 million gallons) of the 580 million (128 million gallons) the city got through each day came from other sources. Three small desalination plants, groundwater from two aquifers and a recycling project at one of the city’s large waste-water treatment plants will come on stream over the next three months, significantly increasing that figure.

Fourth, personal water consumption continues to fall, and is estimated to be 95 litres (21 gallons) a day on average. This is almost twice the 50-litre limit, but it’s also evidence that there is a lot of scope for improvement. In conversation with Zille last week, talk radio host John Maytham mentioned that the members of his household had cut their consumption to 41 litres (9 gallons) a day, but I can top that: the four adults in our house are using 30 litres (6.6 gallons) each, and it really hasn’t been that hard. I am ashamed to note that we used seven times as much in January and February of 2000.

Fifth, extra pumping equipment has been installed in the deep end of Cape Town’s second-largest reservoir, Voelvlei, which will make it possible to suck out some of the elusive last 10 per cent (the reservoir is 18 per cent full). This week, the team of engineers responsible for the work is due to move 80 miles south to Theewaterskloof to do the same thing.

The final reason for optimism is that Capetonians have got the message: the crisis is real, “day zero” is close (the latest estimate is May), the apocalypse could easily be “now now”, to use a local idiom meaning “not now, maybe soon”.

What does this realisation mean in practice? Panic buying of water containers and chemical toilets; the appearance of water tanks of up to 10,000 litres (2,200 gallons) in gardens and yards across the city; booming business for anyone who can help you to access an alternative supply of water – borehole drillers, pump suppliers, manufacturers of “water from air” machines; the death of the lawn, in every possible way; abandonment of swimming pools and bathtubs; fisticuffs in the long queues to fill containers from natural mountain springs.

To use another South African idiom, “we’re making a plan” – and to be honest, we’re quite enjoying it, in the sense that in a city where the gap between rich and poor is among the widest on the planet, we’ve found something to unite us. In a society characterised by often violent conflict and crime, that’s been refreshing.

In this desperate situation, even people in R100 million (£6m) mansions and waterfront apartments can learn from the likes of 31-year-old Akhona Mntuyedwa, who has never had a tap in her house and collects water for her household of five from a standpipe in the township of Khayelitsha, 20 miles outside the city centre.

The Sunday Times asked Mntuyedwa for advice on queueing for water, and she told us: “Very often people get excited or vent their frustrations in the water queues, but this often ends bitterly because of clashing political views. Flirting often leads to fights, and so does gossiping.”

So what of the future? The immediate priority is to #DefeatDayZero, a hashtag coined by the DA. Then we must hope for rainfall of Old Testament proportions this winter. Recycle much more water. Reduce our reliance on reservoirs. Collect and use whatever water we can on our private property. Refuse to go back to wasteful habits when the crisis is over. Keep water prices high. Harness technology, particularly in the agricultural sector, to reduce waste. Install smart meters throughout the city to allow consumption to be controlled. Put in a dual-reticulation system so that non-potable recycled water can be used for everything except drinking. Treat our immense aquifers with the utmost respect so we can always rely on them.

Can Cape Town escape the fate that headlines across the world are predicting? It’s going to be a close-run thing. Whether it does so or not, this city so beloved of holidaymakers around the world will bounce back. It will either be “the city that beat day zero” or “the first city in the world to run out of water”.

Whichever comes to pass, for the difficult years to come as the effects of climate change become the new normal, its efforts and experiences will inform scores of cities around the world.

Dave Chambers is Cape Town bureau chief for The Sunday Times and timeslive.co.za. He emigrated to Cape Town from the UK in 1992

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments