Heat-tolerant corals found in Great Barrier Reef boost hopes for survival

Discovery offers hope that these naturally resilient corals could play a critical role in helping the Great Barrier Reef survive heat stress due to climate crisis

Scientists have uncovered coral colonies in the Great Barrier Reef that can withstand higher temperatures than previously thought, boosting hopes for the survival of corals that have been under dire threat in recent years.

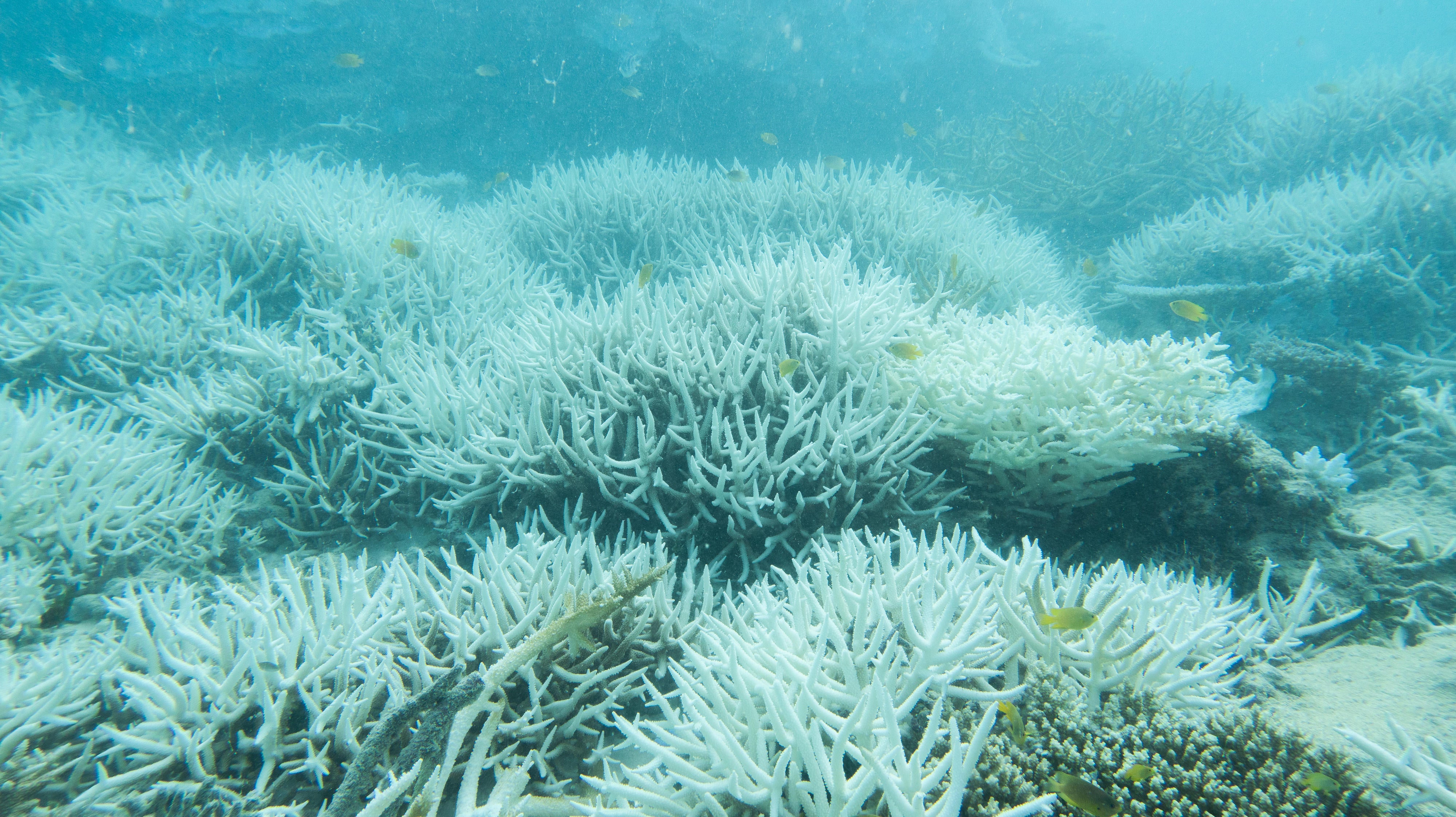

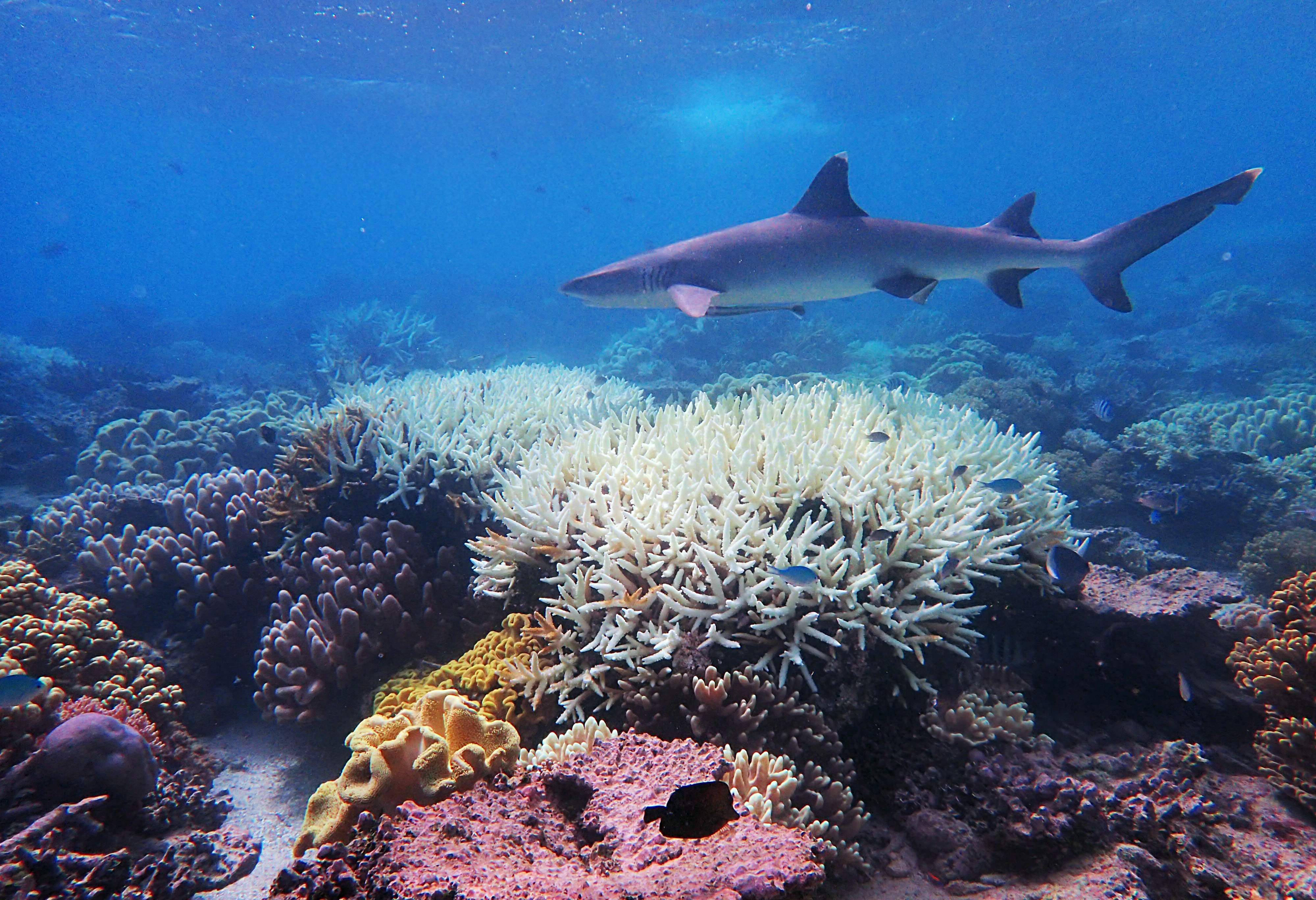

A study published on Monday found that certain corals have a greater ability to resist bleaching, a condition where corals lose their vibrant colour and are at risk of dying when exposed to heat stress, a more frequent and longer phenomenon now due to the climate crisis.

This discovery offers hope that these naturally resilient corals could play a critical role in helping the Great Barrier Reef, which is experiencing its fourth global mass bleaching event due to record-high sea temperatures, survive.

Researchers at Southern Cross University tested over 500 colonies of the table coral acropora hyacinthus from 17 different locations across the Great Barrier Reef.

Using a portable experimental setup, the researchers took their equipment out to sea to measure the heat tolerance of these coral colonies directly on the reefs. This allowed them to observe how different corals responded to increased temperatures and stress in their natural environment.

“We found heat-tolerant corals at almost all the reefs that we studied, highlighting how corals across the entire Great Barrier Reef may hold the key to protecting and restoring the reef,” the lead author of the study Melissa Naugle said.

Heat-tolerant corals are colonies that can survive in warmer water without bleaching. Coral bleaching occurs when corals are stressed by rising sea temperatures and expel the algae living in their tissues, which they rely on for food. Without these algae, corals turn white and become more vulnerable to disease and death.

The ability to withstand heat varies among coral colonies, and this variation is important for the survival of coral reefs.

Ms Naugle explained: “Naturally occurring heat tolerance variation is crucial for corals to adapt to climate warming and for the success of restoration initiatives.”

One of the most important findings from the study is that not all corals are equally affected by rising temperatures. Some coral colonies, due to genetic differences, are more resilient to heat than others.

This is essential for the process of natural selection, where the more resilient corals are likely to survive and pass on their heat-tolerant traits to future generations.

“Differences between individual corals provide the fuel for natural selection to produce future generations of more tolerant corals,” said Dr Line Bay, senior principal research scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS) and co-author of the study.

In other words, as ocean temperatures continue to rise, these more heat-tolerant corals could help rebuild and restore the reef by producing offspring better suited to the warming environment.

The next step for the research team is to analyse the genetic makeup of these heat-tolerant corals using DNA sequencing.

By identifying which specific genes contribute to heat tolerance, scientists could better understand how these resilient corals adapt to their changing environment and use this information to inform conservation strategies.

The discovery of heat-tolerant corals has significant implications for coral restoration programmes. One approach is selective breeding, where corals with the strongest heat tolerance are bred to produce offspring with even greater resilience to warming waters. This method could help speed up coral adaptation to climate change.

“Selective breeding could accelerate adaptation by producing coral offspring better suited to warmer waters,” Dr Emily Howells, a co-author and senior research fellow at the university, said.

However, she added that the effectiveness of this approach depends on how much of the heat tolerance is tied to genes that can be passed on to future generations.

Currently, the most heat-tolerant corals identified in this study are being used in selective breeding trials as part of the RRAP, a large-scale initiative aimed at protecting and restoring the Great Barrier Reef.

While the discovery of heat-tolerant corals offers a promising path forward, scientists stress that it’s not a complete solution to the broader threat of climate change.

The Great Barrier Reef has been severely impacted by a series of mass bleaching events, and rising global temperatures continue to pose a significant risk.

Coral bleaching is becoming more frequent and severe, and many experts fear that if global temperatures rise by more than 1.5C, the vast majority of coral reefs worldwide could be wiped out.

“This work shows that naturally heat-tolerant corals can be targeted for large-scale reef restoration and conservation efforts, helping to protect this critical ecosystem from the warming ocean temperatures that are already locked in due to climate change,” Dr Cedric Robillot, executive director of the reef restoration and adaptation program, said.

Despite these restoration efforts, Ms Naugle and her team say that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is still the most crucial factor in ensuring the long-term survival of coral reefs.

“While restoration initiatives like selective breeding may strengthen coral populations, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the most critical action we can take to give coral reefs the best future possible,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks