COP21: Paris deal won't save low-lying island nations from rising sea levels, Kiribati President warns

Nation at mercy of climate change warns that agreed 2°C limit will not be not enough

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The climate deal struck by 195 nations in Paris will fail to save low-lying island nations from being overcome by rising sea levels, the President of Kiribati has warned.

Kiribati lies in the Pacific Ocean 4,000 miles from Australia and its average height is just two metres above sea level, putting it among the countries most threatened by climate change.

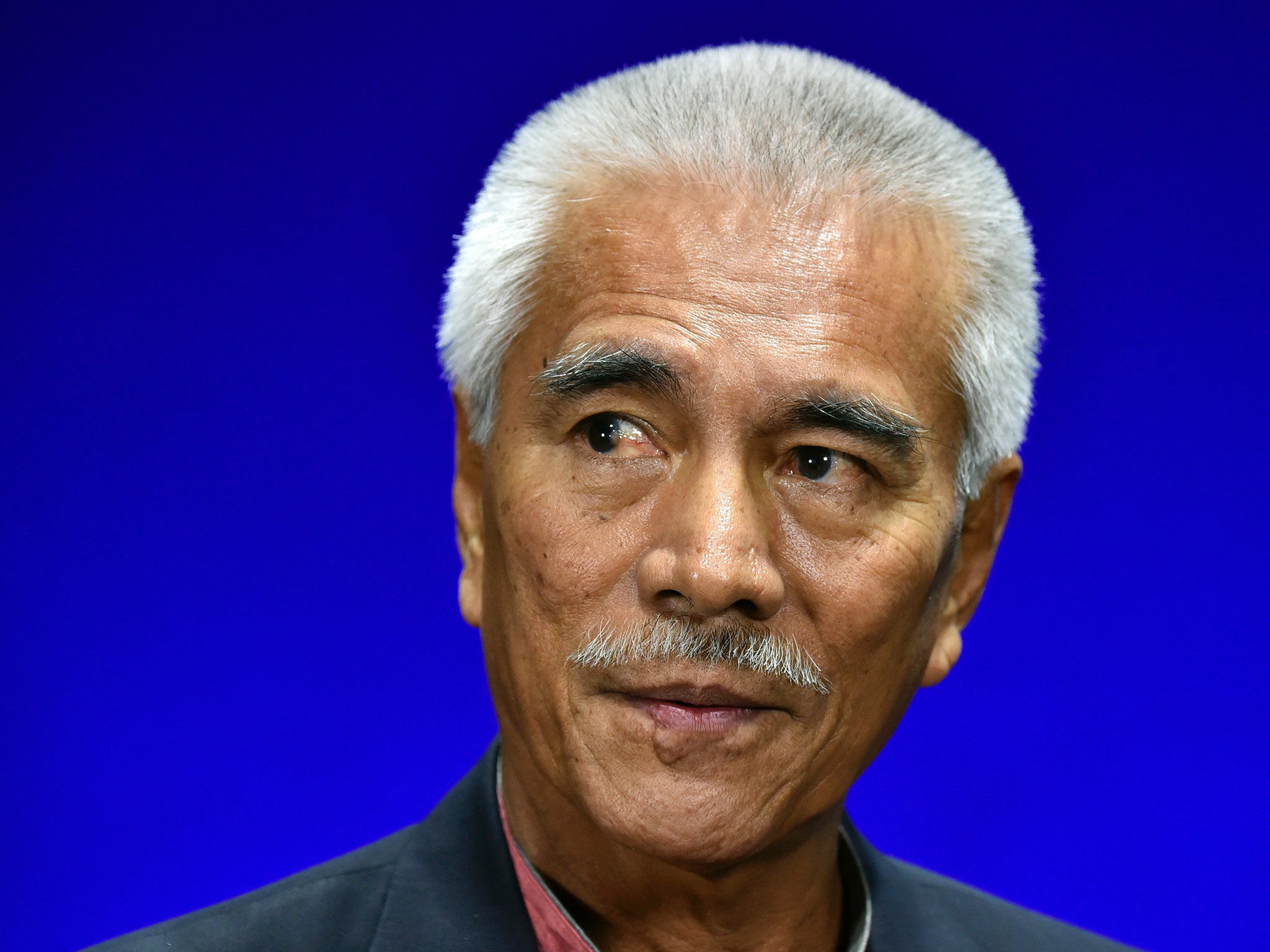

The deal struck in Paris at the weekend to limit temperature rises from global warming to 2°C is too little, said Kiribati’s President, Anote Tong.

He and other leaders from island states had called for the rise to be limited to 1.5°C at the most “if we are to be given a chance” of surviving.

Asked if the Paris accord would be enough, President Tong told the BBC: “No, I don’t think so. Even with 1.5 degrees, we would still have a problem.”

Crucial to his hopes, however, is a fund agreed in Paris that should help Kiribati and other islands adapt to climate change – if enough money is put into it by developed nations.

The next test, he said, was to see “how committed” wealthy countries were to providing the promised $100bn for the fund to assist vulnerable nations suffering loss and damage from climate change.

Mr Tong’s belief that any rise above 1.5°C would be a disaster was backed by Tony de Brum, Foreign Minister of the Marshall Islands.

During the negotiations Mr de Brum had repeated the mantra “1.5 to stay alive”. However, while aware the deal was not a panacea, he said it offered hope.

“We have made history,” he said as the accord was agreed. “With this agreement, I can go back home to my people and say we now have a pathway to survival.

“Climate change won’t stop overnight, and my country is not out of the firing line just yet, but today we all feel a little safer.”

This hope was shared by 18-year-old Marshall Islands resident Selina Leem, who addressed the Paris conference, handing out pieces of coconut leaf to delegates to remind them of her homeland and their contribution to helping save “a little island and the whole world”.

She said: “This agreement is for those of us whose identity, whose culture, whose ancestors, whose whole being, is bound to their lands.

“This agreement should be the turning point in our story, a turning point for all of us.”

Some small island states’ politicians were reassured that the deal agreed at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change conference would go a long way towards protecting them.

Thoriq Ibrahim, the Environment Minister for the Maldives – an island nation in the Indian Ocean that is no more than 2.4m above sea level – described the deal as a victory as he arrived home last night.

Before leaving Paris, he had said: “I hope it will not take another 25 years to achieve our goals. I hope that my children and my grandchildren can be thankful for the work we have done here.”

Small island nations are among the most threatened from the impacts of climate change, the IPCC says, with sea-level rises and the impacts of extreme weather cited as the chief problems.

“Many small island states are threatened with partial or virtually total inundation by future rises in sea level,” the IPCC said in a statement. “In addition, increased intensity or frequency of cyclones could harm many of these islands.”

As sea levels rise, the inhabitants of small islands are increasingly forced to move to higher ground or emigrate to other countries. Plants and animals found only on these islands are threatened with extinction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments