Antarctica's floating ice shelves have lost enough water in 25 years to fill the Grand Canyon

Although there is variation across the continent, overall the ice is melting faster than it is being replaced

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The volume of water loss from Antarctica’s floating ice shelves over the past 25 years would fill the Grand Canyon, according to a new study published on Monday.

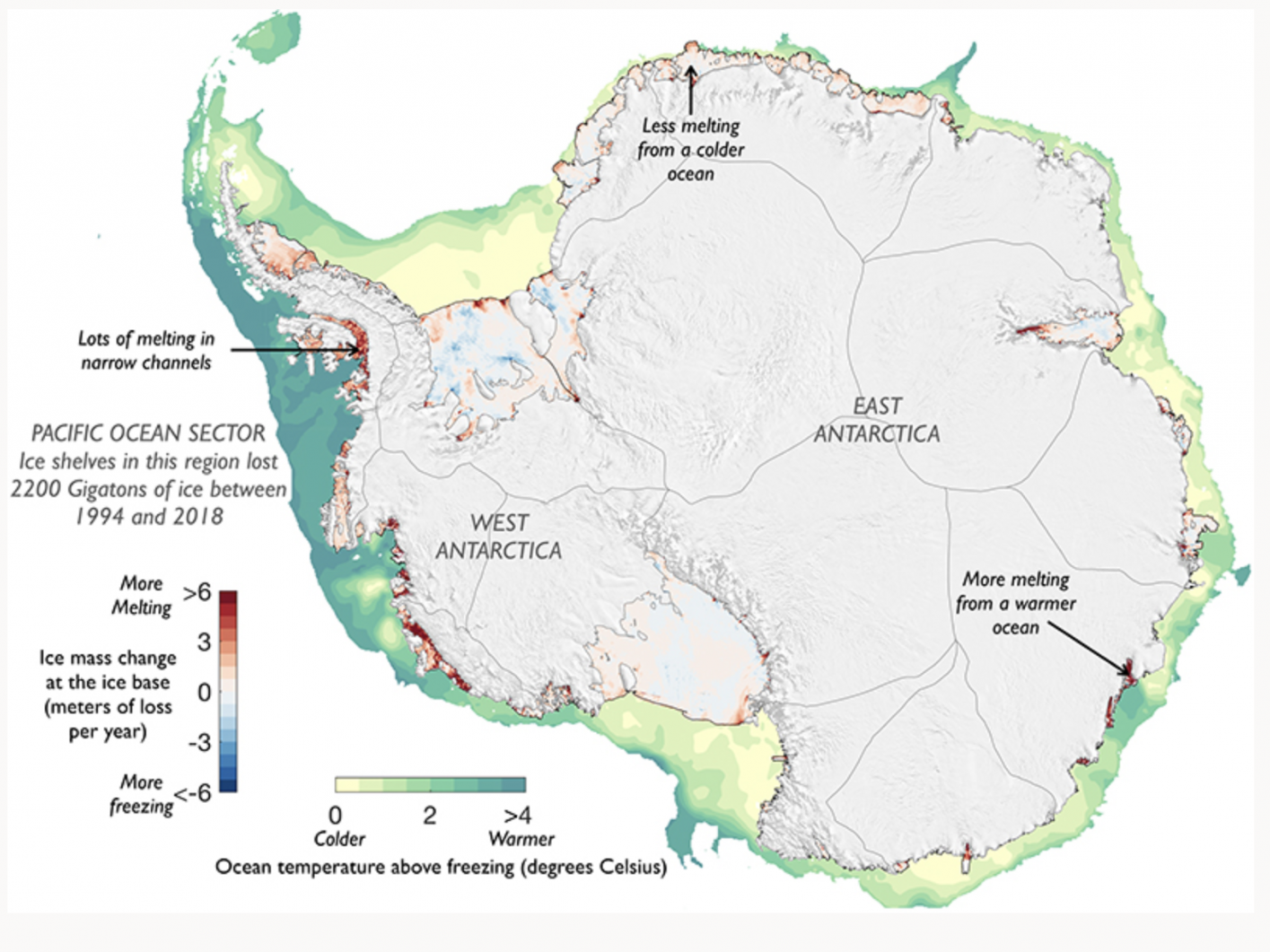

The continent’s ice shelves were found to have lost nearly 4,000 gigatons since 1994 due to melting from increased heat in the ocean as a result of the climate crisis.

Although there was much variation in the rate at which the ocean is melting the ice shelves, overall the ice is melting faster than it is being replaced in Antarctica.

Ice shelf loss does not directly impact sea-level rise as they are already floating in the water. However ice shelves form gigantic buttresses to slow the slide of ice sheets into the ocean and therefore, as they shrink, their ability to hold back ice sheets begins to falter.

Antarctica holds enough ice to raise sea levels globally by an estimated 197 feet (60 metres). The West Antarctic ice sheet, considered to be in a precarious position by some scientists, would increase global seal levels by 10 feet (3m) if it were to melt completely.

Global sea levels have risen by more than six inches in the past 70 years, with half of that occurring since 2000. Even half a foot of sea-level rise has led to a 233 per cent average increase in tidal flooding across the US, according to Sealevelrise.org.

Our rapidly-warming planet causes sea levels to rise on two fronts. Warmer temperatures melt ice sheets and glaciers, leading the run-off to flow into oceans. The ocean also absorbs excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions and warm water expands, taking up more space than colder water.

The new study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, involved researchers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, Earth and Space Research in Corvallis, Oregon and Colorado School of Mines.

The research is based on 25 years worth of data from four European Space Agency (ESA) satellite missions along with NASA ice velocity data and computer modelling, charting a detailed history of the losses around the edges of the continent.

It is notoriously difficult to study Antarctic ice shelves due to their size and remote location so satellites offer a practical solution. They send radio waves to the ground up to 20,000 times a second, allowing scientists to measure the travel time of those waves and determine the precise height of land or ice.

This method allowed for the first-ever analysis of melting across all Antarctic ice shelves, totalling an area of 580,000 square miles (1.5million sq km) – more than three times the size of Spain.

Lead author and Scripps Oceanography graduate student, Susheel Adusumilli, said: “This is the most convincing evidence so far that long-term changes in the Southern Ocean are the reason for ongoing Antarctic ice loss.

“It’s incredible that we are able to use satellites that orbit around 500 miles above the earth to see changes in regions of the ocean where even ships can’t go.”

The study also identified the ocean depths where melting is occurring, which has impacts beyond sea-level rise. Melting ice leads to colder and fresher water rushing into the ocean which affects the global climate and ocean circulation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments