How climate change is triggering a migrant crisis in Vietnam

Global warming could be responsible for forcing 24,000 people to leave the Mekong Delta every year

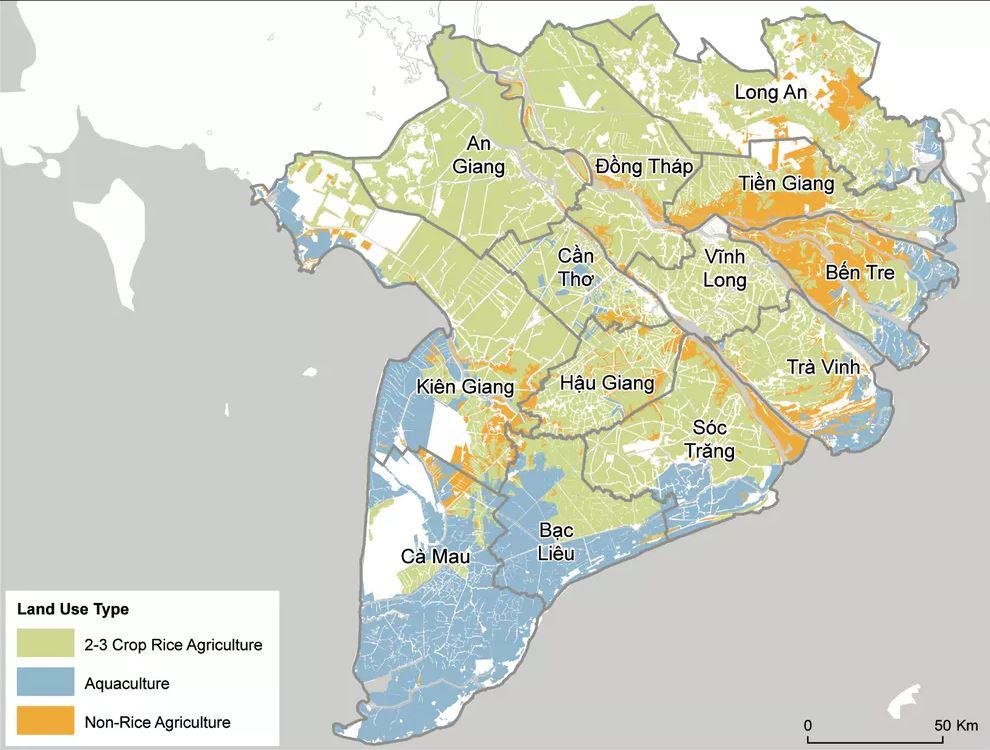

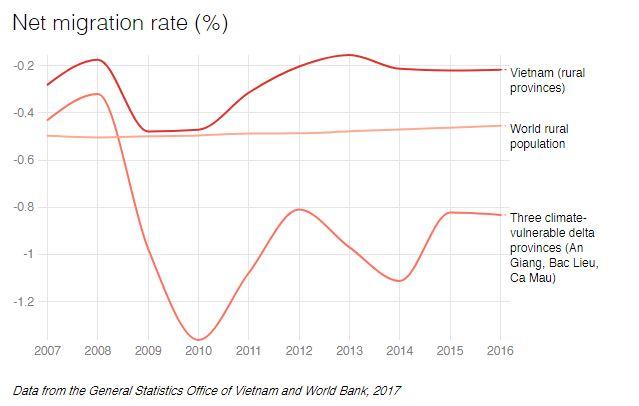

The Vietnamese Mekong Delta is one of Earth’s most agriculturally productive regions and is of global importance for its exports of rice, shrimp and fruit. The 18 million inhabitants of this low-lying river delta are also some of the world’s most vulnerable to climate change. Over the last 10 years around 1.7 million people have migrated out of its vast expanse of fields, rivers and canals, while only 700,000 have arrived.

On a global level, migration to urban areas remains as high as ever: one person in every 200 moves from rural areas to the city every year.

Against this backdrop it is difficult to attribute migration to individual causes, not least because it can be challenging to find people who have left a region in order to ask why they went, and because every local context is unique.

But the high net rate of migration away from Mekong Delta provinces is more than double the national average, and even higher in its most climate-vulnerable areas. This implies that there is something else – probably climate-related – going on here.

In 2013 we visited An Thanh Dong commune in the Soc Trang Province aiming to collect survey data on agricultural yields. We soon realised that virtually no farmers of An Thanh Dong had any yields to report. The commune had lost its entire sugarcane crop after unexpectedly high levels of saltwater seeped into the soil and killed the plants. Those without a safety net were living in poverty. Over the following weeks hundreds of smallholders, many of whom had farmed the delta for generations, would tell us that things were changing and their livelihoods would soon be untenable.

In 2015-2016 disaster struck with the worst drought in a century. This caused saltwater to intrude over 80km inland, and destroyed at least 620sq miles of crops. In Kien Giang (population 1.7 million), one of the worst affected provinces, the local net migration rate jumped, and in the year that followed around one resident in every 100 left.

One relatively low-profile article by Vietnamese academics may be a vital piece of the puzzle. The study, by Oanh Le Thi Kim and Truong Le Minh of Van Lang University, suggests that climate change is the dominant factor in the decisions of 14.5 per cent of migrants leaving the Mekong Delta. If this figure is correct, climate change is forcing 24,000 people to leave the region every year. And it’s worth pointing out the largest factor in individual decisions to leave the Delta was found to be the desire to escape poverty. As climate change has a growing and complex relationship with poverty, 14.5 per cent may even be an underestimate.

There are a host of climate-linked drivers behind migration in the delta. Some homes have quite literally fallen into the sea as the coast has eroded in the south-western portion of the delta – in some places 100m of coastal belt has been lost in a year. Hundreds of thousands of households are affected by the intrusion of saltwater as the sea rises, and only some are able to switch their livelihoods to saltwater tolerant commodities. Others have been affected by the increased incidence of drought, a trend which can be attributed in part to climate change, but also to upstream dam construction.

Governments and communities in developing countries around the world have already begun taking action to manage climate change impacts through adaptation. Our recent research in Vietnam flags a warning about how this is being done. We show that a further group of people are being forced to migrate from the Mekong due to decisions originally taken to protect them from the climate.

Thousands of kilometres of dykes, many over four-metres high, now criss-cross the delta. They were built principally to protect people and crops from flooding, but those same dykes have fundamentally altered the ecosystem. The poor and the landless can no longer find fish to eat and sell, and the dykes prevent free nutrients being carried onto paddies by the flood.

All this demonstrates that climate change threatens to exacerbate the existing trends of economic migration. One large scale study of migration in deltas has found that climate factors such as extreme floods, cyclones, erosion and land degradation play a role in making natural resource-based livelihoods more tenuous, further encouraging inhabitants to migrate.

To date, traditional approaches to achieving economic growth have not served the most vulnerable in the same way they have served those living in relative wealth. This was demonstrated most dramatically by the revelation that the number of undernourished people on earth rose by 38 million last year – a shift for which climate change is partly responsible. This took place despite global GDP growth of 2.4 per cent.

It is with these failures in mind that society must prepare an equitable and sustainable response to climate change and what seems a looming migrant crisis.

Alex Chapman is a research fellow in human geography at the University of Southampton and Van Pham Dang Tri is head of the department of water resources at Can Tho University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks