Bug haters, beware: After 200 years, the cicadas are here by the trillions

Two broods of cicadas will emerge at the same time in the coming weeks. The next time this will happen? 2245. Katie Hawkinson reports

A rare phenomenon that hasn’t occurred since Thomas Jefferson was in the White House is set to take place - but possibly for the last time.

It isn’t a comet or the upcoming solar eclipse — rather, the emergence of trillions of cicadas. Two broods of the flying insects — named XIII and XIX — are set to invade the east coast and midwest in the coming weeks after last burrowing out of the soil together in 1803.

Their next co-emergence isn’t expected until 2245.

“I’ve actually been looking forward to this for many years now,” Dr Katie Dana, an entomologist and cicada expert from Illinois told The Independent. “I’ve been trying to spread the word — people haven’t listened until this year.”

“I’m just so excited,” added Dr Dana, who goes by “Cicadidae (Ci - Katie - D) enthusiast”, on X/Twitter. She plans to share the “magical” event with her son.

Cicadas, best known for their loud “singing” or chirping, are classed as different broods, depending on when they emerge from spending most of their lives underground.

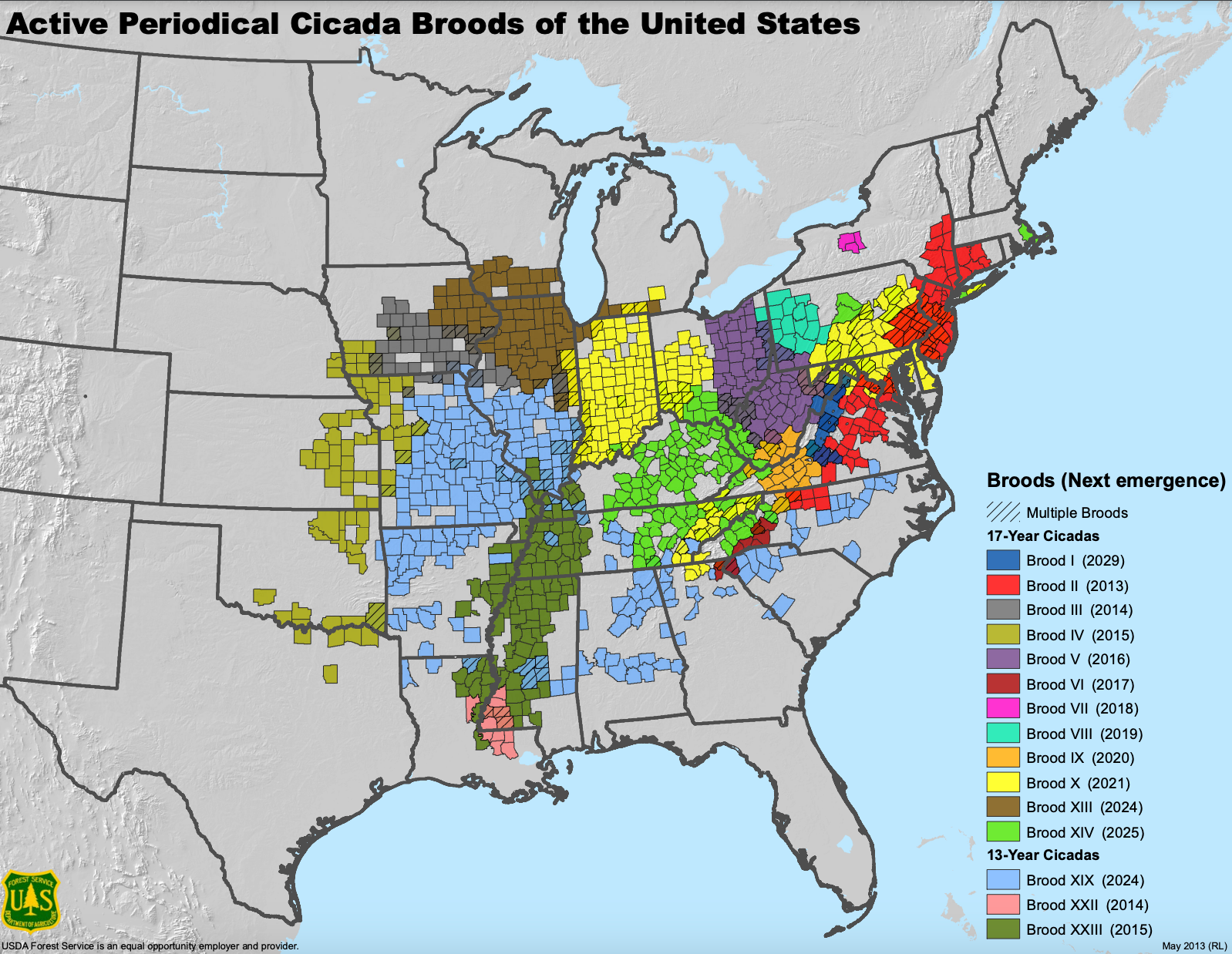

There are 15 “periodical” cicada broods in the US — three which emerge on 13-year cycles, and the rest every 17 years. That means there’s usually just one type of cicada at a time.

This year is expected to be one for the record books. Brood XIII, which appears every 17 years, and Brood XIX, on a 13-year cycle, will coincide for the first time in over 200 years. These cicadas are smaller varieties, growing to 1.4 inches, but other broods can double that and have 8-inch wingspans.

Ground zero for this event is Illinois but around a dozen states will experience trillions of the winged insects — and then unavoidable heaps of carcasses.

The good news for farmers is that cicadas don’t attack plants — although they can cause damage to fruit trees. The female periodical cicada is known to slit the bark on young tree branches to lay her eggs.

While some might be freaked out by the cicada invasion — and the fear of cicadas is real and common — others are embracing the natural phenomenon.

A professor in Ohio has created a free app, Cicada Safari, so users can upload photos of the insects and track where the biggest numbers emerge.

In Illinois, the Lake County Forest Preserves is holding a “Cicadafest” with demonstrations, opportunities to dress up as cicadas and get involved in an insect hunt.

And the more culinary adventurous might enjoy them as a springtime snack. Cicadas can be cooked into stir frys, dumplings and even rhubarb pie, according to the “Cicada-licious” cookbook.

But after the hottest year in human history, experts are worried about cicadas’ resilience in face of the climate crisis.

It’s feared that humans could wipe entire species out of existence from fuelling a fungus that turns cicadas into “zombies” to destroying their habitats.

Feeding frenzy

For those who live in cicada-infested areas, it might be hard to imagine a decline in the species.

Periodical cicadas ensure their survival by producing so many offspring that their large number of predators are quickly satiated, making an insignificant dent in numbers.

“They overwhelm their predators, so everybody gets full,” Dr Dana said.

However, this evolutionary development means that even a small dip in population numbers caused by external factors like higher temperatures or forest destruction, could allow predators to wipe out entire broods, she explained.

Cicada populations are difficult to study over the long-term because they emerge so rarely, said experts at the University of Connecticut.

However, all available evidence indicates the climate crisis will take a toll.

“What climate change might eventually have impact on is their population sizes, if a brood emerges in a year that has a high mortality rate due to adverse conditions,” Dr Douglas Yanega, an entomologist at University of California, Riverside, toldThe Independent via email.

Weather conditions don’t impact when cicadas emerge, Dr Yanega said, but environmental factors do have consequences.

‘It gets smelly’

While the consequences of a hotter world are still being understood, humans have already impacted cicada species.

In order to grow, cicadas must moult by shedding their hard, outer layer of protection, called an exoskeleton. During this process, the insects take shelter in trees as they wait for a larger exoskeleton to regrow. Without trees or thick forest underbrush to hide in, cicadas will die prematurely.

“Any sort of deforestation is absolutely going to affect their numbers,” Dr Dana said.

In areas where trees and shrubs have been cleared, cicadas have been observed emerging from the ground and piling up in the grass, unable to moult.

“They’re everywhere, stuck in their shells,” the scientist said. “It gets smelly, and you feel bad for them because they’re stuck, just dying slowly.”

Deforestation is driven both by human development and an overheating planet. In the US, the increase in wildfires over the past 20 years has destroyed 48,000 square miles of tree cover, according to Global Forest Watch. More frequent and intense droughts have made this worse, sucking trees of moisture and leaving them primed to burn.

Two US cicada broods are already known to have gone extinct - XI and XXI.

Brood XI died out sometime after 1954 when their last emergence was recorded in Connecticut. However, their extinction was unrelated to deforestation or urban growth, according to University of Connecticut entomologists. Some scientists have suggested that the brood was vulnerable because it was made up of a single sub-species and existed in less than ideal environmental conditions.

Brood XXI went extinct in 1870 but experts have little information on why they disappeared.

‘Saltshakers of death’

One of the biggest threats to cicadas is Massospora, a fungus which infects insects as they burrow out of the soil, causing them to die prematurely.

In an echo of the fictional HBO series The Last of Us, the fungal infection turns the insects into zombie-like creatures. The fungus causes spores to grow in their abdominal cavity, pouring out of the cicadas as they fly, earning them the nickname of “saltshakers of death,” said Dr Dana.

“You could pick up an individual and if you push on the tip of its abdomen, it falls off and you can see all of the spores inside,” she added.

During this year’s rare co-emergence, the scientist hopes to study what impact the climate crisis might have on Massospora.

“There’s a lot of questions about this fungus. Is it going to increase, or is it going to decrease?” she said.

It’s just one of many unanswered questions related to cicadas, and Dr Dana said this spring’s rare event is the perfect opportunity to gather the data and samples to learn more.

“I like to remind people this is like a natural wonder of the world, and nowhere else do you see this sheer biomass of organisms in one place,” she said. “It is magical.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments