Arizona's rains: Monsoon, moths, militia, and me

Every year, the rains arrive in southern Arizona and turn the arid desert into a home for millions of rare moths, spiders and snakes – not to mention the tens of thousands of collectors who hope to capture them. Douglas Main joins them.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before the monsoon rains lured me to southern Arizona, I had never been shot at. Nor had I seen wild rattlesnakes or the double-barrelled mandibles of a sun spider. Certainly, I'd never been tailed by border-control vigilantes or encountered a famous entomologist in a ghost town.

In July, waters from the sky return to this typically arid region. What seemed dead in June's sweltering heat gradually comes back to life. The dun shafts of ocotillo plants burst with green leaves, and the agaves bloom. Billions of ants take to the air in nuptial flights to mate, the eggs of trillions more insects hatch, and grubs under logs pupate into shimmering beetles. This arthropod feast brings out countless amphibians and reptiles, birds and mammals, and clouds of bats thick enough to block out the starlight.

It also draws humans: entomologists and bug lovers of all stripes and striations, “herpers” looking for snakes and frogs, birders, bat-watchers and botanists. Tens of thousands of people come here during the monsoon for these activities, according to the Arizona Office of Tourism. Some choose to hike and photograph, some to wrangle rattlesnakes and others to collect scorpions and spiders for private stashes or zoos. Many American zoos and insectariums are populated with descendants of this region. “Like moths to the blacklight, we are drawn here each year,” Jim Melli, an exhibition designer at the San Diego Natural History Museum, says. “Rain in the desert brings it to life in a beautiful and mysterious way.”

Melli is one of a couple of hundred people who make the annual trek to the Invertebrates in Education and Conservation Conference. Attendees take in talks on such topics as how to best raise tiger beetles – a voracious coleopteran predator – and hear progress reports on subjects such as the reintroduction of the endangered Taylor's checkerspot butterfly to the Pacific Northwest. Vendors sell black widows and scorpions, ant queens and vinegaroons, prehistoric-looking arachnids with claws and whiptails that make them appear much more dangerous than they are. And an amiable, fast-talking man named Zack Lemann, chief entomologist at the Audubon Insectarium, can be counted on to make up arthropod-themed rap songs at a moment's notice.

One favourite here is the pepsis wasp – a large, attractive insect with copper-coloured wings also called the tarantula hawk (since it eats the large arachnids). These deadly hunters have the second-most painful sting in the insect kingdom. Justin Schmidt, an entomologist who came up with the Schmidt Pain Index for ranking the most agonising insect stings, wrote that being pricked by one causes “immediate, excruciating pain that simply shuts down one's ability to do anything, except, perhaps, scream”. He compared it to the feeling that “a running hair dryer has just been dropped into your bubble bath”.

I later run into Schmidt while exploring a ghost town called Ruby with another entomologist, Lary Reeves, and his girlfriend. The famous scientist, distinguished by a floppy green felt hat and a moustache, invites us to watch that evening as hundreds of thousands of Mexican free-tail bats come out to feed on insects. Then he gets out his net and snags a few velvet ants, which are also known to deliver nasty stings. He proceeds to thrust a jar into the net and gently ushers an insect into it. “I'm one of the only entomologists to never use a killing jar,” he says. (Field biologists sometimes kill venomous insects in jars filled with substances such as ethyl acetate, in part so they don't get stung.) This probably helps explain why he's been hit a handful of times by tarantula hawks and bullet ants, a tropical species that inflicts the most discomfort of any insect. “Pure, intense, brilliant pain” is how he has described it. “Like walking over flaming charcoal with a 3in nail in your heel.”

This part of the Southwest is where the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts, each with their own unique ecosystems, merge. Multiple mountain ranges give rise to “sky islands”, housing diverse forests and meadows, and stretch into Mexico, providing corridors for tropical species. There is more biodiversity in the Sky Islands region than anywhere else in the US, says Shipherd Reed, the communications manager at the University of Arizona's Flandrau Science Centre.

The region's geography also gives rise to the North American monsoon, whose mere existence comes as a surprise to many (who may be more familiar with the South Asian variety). A monsoon is characterised by a seasonal reversal in winds, along with a change in precipitation. Most of the year, winds blow into Arizona from the west and north-west. In the summer, especially in June, the region becomes extremely hot and dry. This creates a low-pressure system that sucks in winds from the east and south, carrying moisture from the Gulf of Mexico, Gulf of California and eastern Pacific. As the air is forced upward by various mountain ranges, it drops rain. This water is reabsorbed into the air during the hot days and blown north, gradually spreading the monsoon rain like a plume into Arizona and New Mexico. That's why many tropical species occur here and nowhere else in the US. One such creature – found mostly in Mexico, besides a few rare spots in Arizona – is the lowland burrowing tree frog (Smilisca fodiens), a handsome brown-and-green amphibian that spends most of the year underground. It's rare to hear its magnificent mating calls, uttered at a time of explosive activity, during the monsoon season when it briefly comes above ground to breed.

When I arrive in Phoenix, around 10pm on a Saturday in mid-July, Reeves and Trace Hardin, who runs a snake-breeding company, pick me up to go see these frogs. There is a small wrinkle, though: they happen to live in the Vekol Valley. Cut off from the sprawl of Phoenix by two mountain ranges and made up of federal and tribal land, this piece of the desert has become notorious as a corridor for drug and human trafficking. In 2010, several people, including a sheriff's deputy, were shot here, and in June 2012 five bodies were found burned inside a charred SUV. “Active human and drug smuggling area,” declares a notice we pass, posted by the Bureau of Land Management. “Visitors may encounter armed criminals and smuggling vehicles travelling at high rates of speed.” But we don't stop. Upon pulling into a spot where we will meet two others, my compatriots see something. “Rattlesnake!” Reeves says, as he and Hardin jump out of the car. Reeves, almost done with a PhD in entomology at the University of Florida, has a habit of chasing creatures whether he has a net or not; he often grabs them with his bare hands. Hardin shares this predilection for running after animals from which most people would flee; his Instagram largely consists of him holding snakes, often alarmingly close to his face.

The two laugh gleefully as they pursue and take photos of the snake, which is the exact colour of the desert: 1,001 variations of sandy brown. A few moments later, a car arrives with the field biologist Aaron Chambers and one of his friends. Chambers is a large man with a deep tan who always wears tank tops, shorts and sandals, despite the prevalence of snakes and cacti. He says he “is only social during the monsoon season”, surrounded by like-minded naturalists. “At all other times, people can fuck off.” He also carries a .38 handgun.

“That thing will ruin you,” Chambers bellows, before coming nearere to get a good look at the serpent. It's a Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus), the venom of which possesses potent neuro and hemotoxic properties, attacking nerve and blood cells.

Together, we trudge through thick mud, leavened by cow pies from wandering cattle, and joke that in the dung-filled milieu we might contract hookworm. (Later, while changing out of my shoes, I accidentally step on a bombardier beetle, which shoots boiling-hot liquid out of its rear end on to my heel, staining my skin a reddish hue for weeks.) As we approach a streambed swollen with rain, the call of our prey – the burrowing tree frogs – becomes nearly deafening. Months and months of underground isolation now over, it's time to mate. Reeves and Hardin spot a male, his vocal sac expanding like a membrane of bubblegum as he breathes. A few minutes later, a female hops by to check him out.

Several years ago at this spot, Chambers and his girlfriend were surrounded by a dozen vigilantes toting assault rifles, who assumed that he was a drug smuggler or immigrant. He told them he was a US citizen and carrying a gun. A tense stand-off followed, luckily no shots were fired and everyone dispersed. But militia-type movements have popped up in every state next to Mexico, to try to keep illegal immigrants from crossing the border. US Customs and Border Protection has publicly discouraged such activity; meanwhile, the agency apprehended 414,397 people unlawfully entering the country from Mexico in the fiscal year 2013, an average of 1,135 people per day (or 47 per hour).

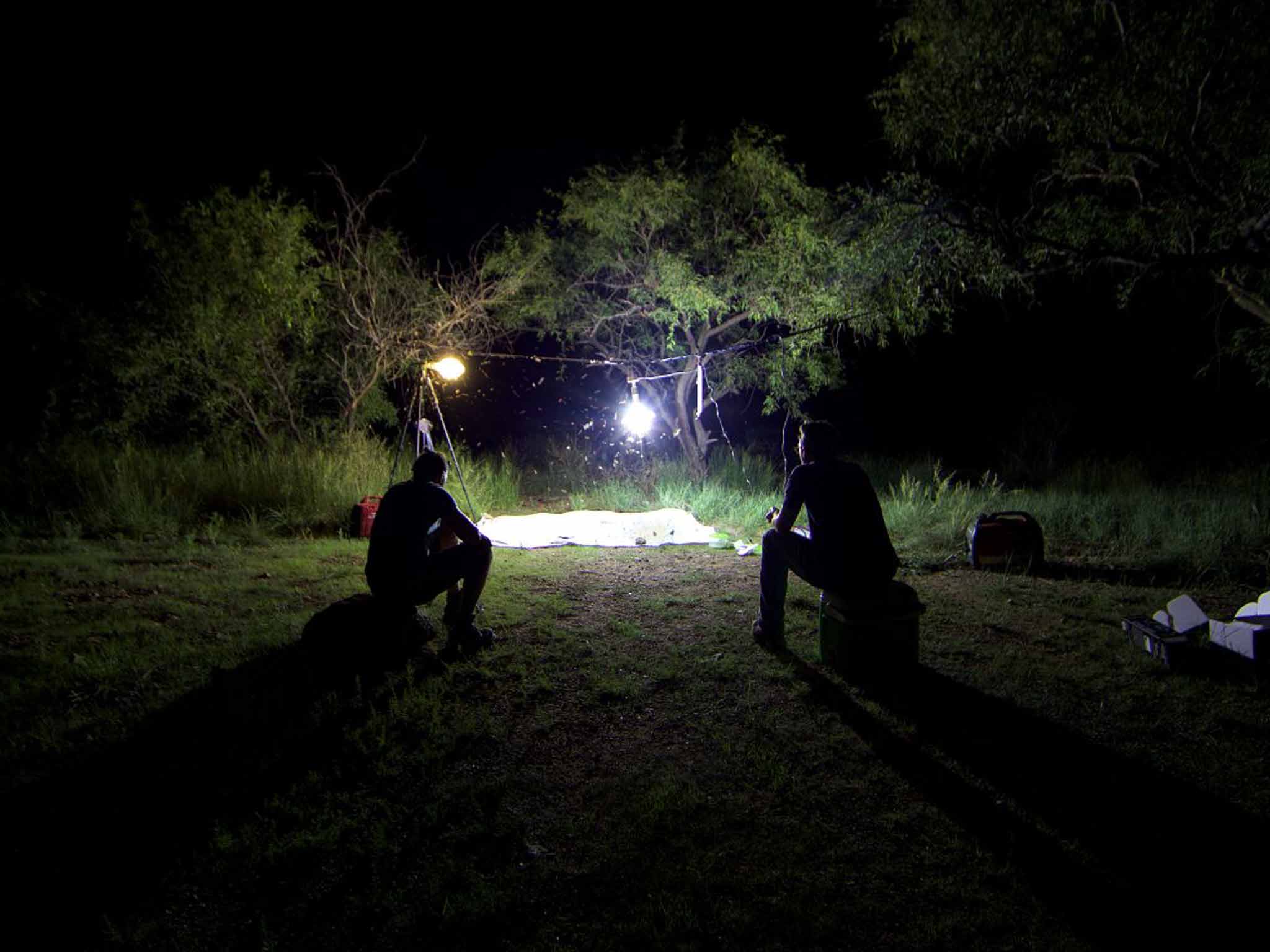

A few days after our frog hunt, on a night when we probably should've been listening to the conference's keynote talk about ants, five of us – me, Reeves, Hardin, Chambers and Isaac Powell, a zookeeper from Miami – hike out to look for insects in California Gulch, a remote part of the Coronado National Forest less than two miles from the Mexican border. When we arrive, we set up two intensely bright lights, powered by two separate generators, as well as a blacklight, to attract insects, a common entomological technique. We also set up a white sheet between them for the bugs to congregate upon. Soon thousands of insects have flocked to it: silk moths, beetles, adult antlions, flies and innumerable others. As we wait and sit back, watching, we enjoy local brews.

After a while, the headlights of an SUV appear. The driver introduces himself as “Cody” and suggests we might be on his property. (We are certain we're on national forest land.) Then the man tells us he's a member of a militia; he shows us his hip-mounted pistol and an AR-15 he keeps in his truck, besides a skull-adorned mask worn while “on patrol”. After he leaves, an animated discussion begins, and Chambers makes his feelings clear about “rednecks who like to play GI Joe”.

Shortly thereafter, we see what looks like somebody's headlamp coming toward us again, in the near distance. And then gunshots, four in rapid succession. I dive to the ground, moths fluttering about my head, as Chambers snaps off the generator. We pack up as quickly as possible and bolt. The next morning, I wander around the conference bleary-eyed, and Nate Nelsona, a curator at a zoo in Wichita, Kansas, gives me a knowing look. “Things can get a bit crazy during the monsoon,” he says. “Too much alcohol, too little sleep, too many bugs.”

During our time in the desert, the entomologists make a couple of exciting discoveries. For one, they find a pregnant northern giant flag moth (Dysschema howardi), whose value Chambers estimates at $700 (£462), between what people are willing to pay for a dried specimen and its egg masses, which can be raised on romaine lettuce with little effort. We also come across the rare and venomous ridge-nosed rattlesnake (Crotalus willardi). A few years back, a man was found dead in this area, with three willardi on his person. The snakes once fetched up to $1,000 in Germany, although it's now illegal to capture them.

Reeves decides to take home some sun spiders, arachnids that possess twin chelicerae, or fangs, that give them a fearsome appearance. Almost “nothing is known about these guys, and I'd like to start collecting material for a publication on them, down the road”, he says.

But they are also just amazing to behold for their own sake. One of the highlights of Schmidt's early experiences in the Arizona monsoon, and a reason he moved to Tucson, was “seeing a sun spider, that buzz saw of a lightning-fast eating machine, in the middle of a whirlwind of flying moth scales”.

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments