What to know about the Atlantic hurricane season that is far from over

Record sea surface temperatures fueled by climate change in the Gulf of Mexico have led to the rapid intensification of Atlantic hurricanes

Following two major hurricanes that left hundreds dead and many displaced amid the destruction, anxious Americans along the southeastern coast are wondering what kind of extreme weather they may face next.

There’s still more than a month until the end of the Atlantic hurricane season, and October is one of its most active months, ranking third behind August and September.

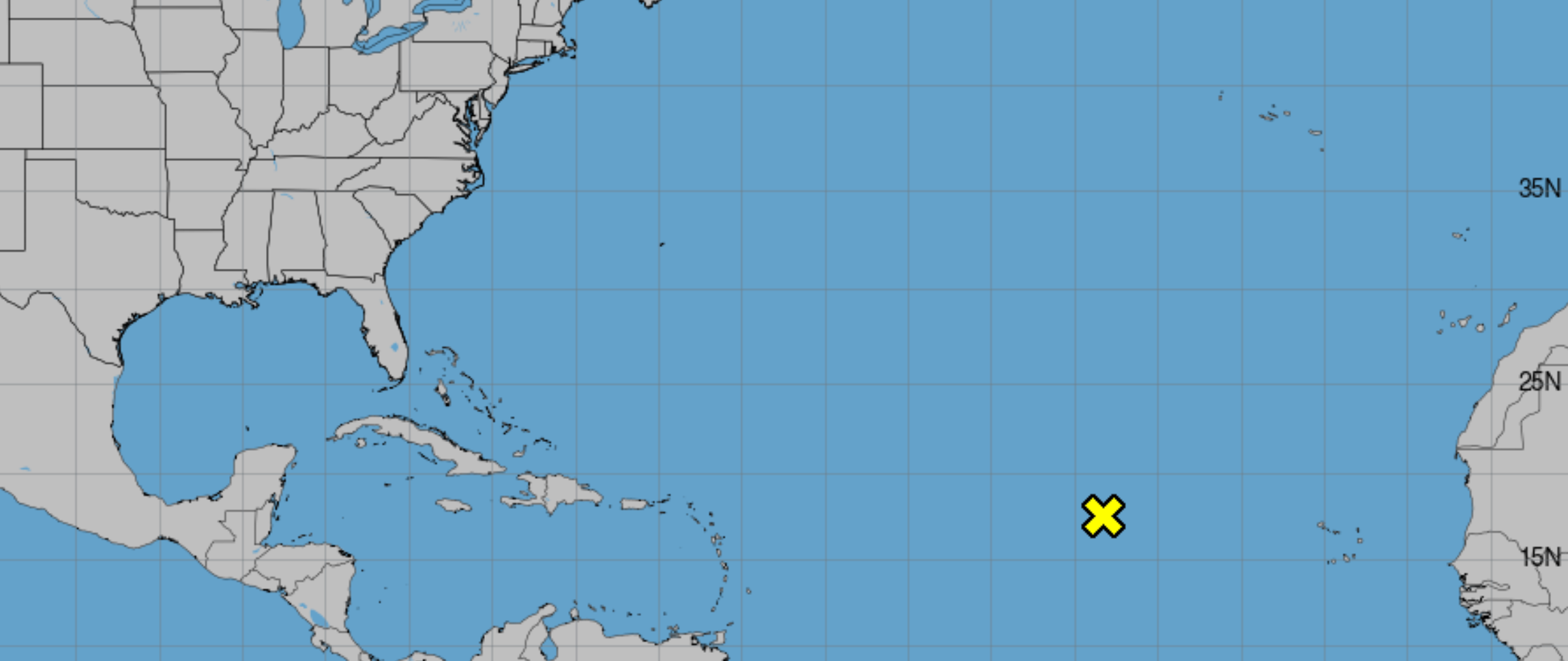

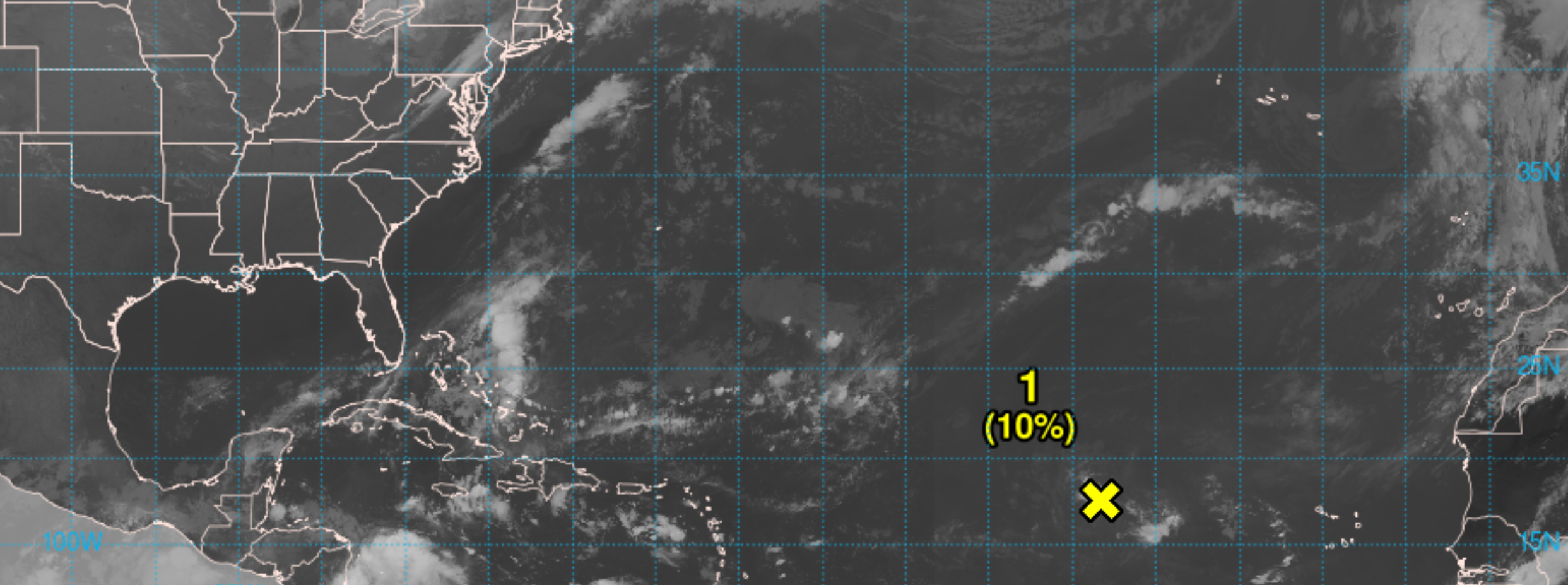

Now, meteorologists are watching a moving area of thunderstorms over the Atlantic Ocean.

On Monday, the National Hurricane Center said that the storm system could develop into a tropical depression as it approaches, or moves near the northern Leward Islands later in the week.

But, the National Weather Service in Tampa said it remains too early to know where it would go or how strong it could be if it develops.

“Now is not the time to panic about this shaded orange area,” the office cautioned on social media. This warning comes after false rumors spread on social media about another storm imminently hitting Florida.

A disturbance like this has a 40 percent chance of developing into a more menacing storm system over the Atlantic within the next seven days. The agency said it has a 10 percent chance of cyclone formation in the next 48 hours and that the system is forecast to head westward and toward warmer waters, where conditions could be more favorable by mid-week.

If it becomes a cyclone, it would need to continue to strengthen to develop into the season’s 14th named storm. The next two tropical cyclone names for the season are Nadine and Oscar.

There have been 13 named storms thus far during this year’s Atlantic hurricane season.

Extremely warm temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico have fueled activity, helping storms to pick up size and strength. To form, hurricanes need tropical water temperatures of just above 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

Hurricane Milton was the Gulf’s strongest late-season storm on record, and the strongest hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Rita hit in 2005.

And the only storm more deadly for the continental US than Hurricane Helene — which struck late last month — was Hurricane Katrina, which also slammed the Gulf Coast during the autumn of 2005.

Climate change has contributed to the problem, causing hurricanes to bring more intense rainfall and increased storm surge from rising seas. For every 1 degree of warming, the air can hold an extra 4 percent of moisture, according to nonprofit Climate Central.

The organization World Weather Attribution, which was initially funded by Climate Central, said that the burning of fossil fuels made increased sea surface temperatures during the track of Helene between 200 to 500 times more likely than they would have been otherwise.

Climate Central found earlier this month that climate change made record sea surface temperatures in the region where Milton developed between 400 to 800 times more likely.

The production of fossil fuels sends greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, into the Earth’s atmosphere. There, the gases trap heat energy from the Sun, warming the Earth and preventing that heat from being expelled into space. As the planet warms with the amount of emissions trapped in the atmsophere rising, the ocean absorbs the excess heat, leading to rising ocean temperatures.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks